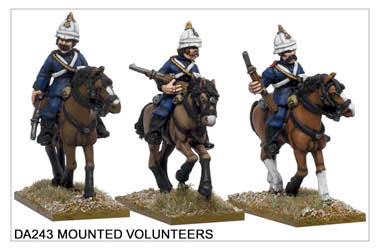

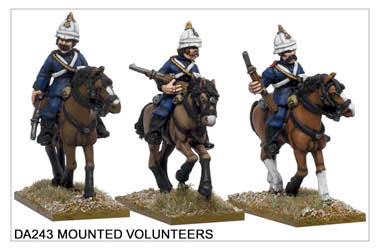

THE OUTBREAK OF THE WAR—TRANSPORT LEAVING ENGLAND FOR THE CAPE. Drawing by Charles J. de Lacia. From all accounts the two hostile columns numbered respectively 4000 and 9000 men, and against these forces Sir Penn Symons had at his command in all about 4000. Among these were the 13th, 67th, and 69th Field Batteries, the 18th Hussars, the Natal Mounted Volunteers,

Drawing by Charles J. de Lacia. From all accounts the two hostile columns numbered respectively 4000 and 9000 men, and against these forces Sir Penn Symons had at his command in all about 4000. Among these were the 13th, 67th, and 69th Field Batteries, the 18th Hussars, the Natal Mounted Volunteers, the 8th Battalion Leicester Regiment, the 1st King's Royal Rifles, the 2nd Dublin Fusiliers, and several companies of mounted infantry. But on the Dublin Fusiliers, the King's Royal Rifles, and the Royal Irish Fusiliers fell the brunt of the work, the task of capturing the Boer position, and the magnificent dash and courage with which the almost impossible feat was accomplished brought a thrill to the heart of all who had the good fortune to witness it.

the 8th Battalion Leicester Regiment, the 1st King's Royal Rifles, the 2nd Dublin Fusiliers, and several companies of mounted infantry. But on the Dublin Fusiliers, the King's Royal Rifles, and the Royal Irish Fusiliers fell the brunt of the work, the task of capturing the Boer position, and the magnificent dash and courage with which the almost impossible feat was accomplished brought a thrill to the heart of all who had the good fortune to witness it.

Though the fight was a successful one, a grievous incident occurred. The 18th Hussars had received orders at 5.40 a.m. to get round the enemy's right flank and be ready to cut off his retreat. They were accompanied by a portion of the mounted infantry and a machine-gun. Making a wide turning movement, they gained the eastern side of Talana Hill and there halted, while two squadrons were sent in pursuit of the enemy. foundry From that time, though firing was heard at intervals throughout the day, Colonel Moeller, with a squadron of the 18th Hussars and four sections of mounted infantry, was lost to sight. The rain had increased and the mist covered the hills, and it was believed that in course of time this missing party would return. But the belief was vain. In a few days it was discovered that they were made prisoners and had been removed to Pretoria. The following is a list of the gallant officers who were so unluckily captured:—

foundry From that time, though firing was heard at intervals throughout the day, Colonel Moeller, with a squadron of the 18th Hussars and four sections of mounted infantry, was lost to sight. The rain had increased and the mist covered the hills, and it was believed that in course of time this missing party would return. But the belief was vain. In a few days it was discovered that they were made prisoners and had been removed to Pretoria. The following is a list of the gallant officers who were so unluckily captured:—  fusiliers arch Dublin Colonel Moeller, 18th Hussars; Major Greville, 18th Hussars; Captain Pollok, 18th Hussars; Captain Lonsdale, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Le Mesurier, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Garvice, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Grimshaw, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Majendie, 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps; Lieutenant Shore, Army Veterinary Department, attached to 18th Hussars.

fusiliers arch Dublin Colonel Moeller, 18th Hussars; Major Greville, 18th Hussars; Captain Pollok, 18th Hussars; Captain Lonsdale, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Le Mesurier, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Garvice, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Grimshaw, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Majendie, 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps; Lieutenant Shore, Army Veterinary Department, attached to 18th Hussars.  An official account of the circumstances which led to the capture was supplied by Captain Hardy, R.A.M.C., who said: "After the battle, three squadrons of the 18th Hussars, with one Maxim, a company of the Dublin Fusiliers, a section of the 60th Rifles and Mounted Infantry, Colonel Moeller commanding, kept under cover of the ridge to the north of the camp, and at 6.30 moved down the Sand Spruit. On reaching the open the force was shelled by the enemy, but there were no casualties.

An official account of the circumstances which led to the capture was supplied by Captain Hardy, R.A.M.C., who said: "After the battle, three squadrons of the 18th Hussars, with one Maxim, a company of the Dublin Fusiliers, a section of the 60th Rifles and Mounted Infantry, Colonel Moeller commanding, kept under cover of the ridge to the north of the camp, and at 6.30 moved down the Sand Spruit. On reaching the open the force was shelled by the enemy, but there were no casualties. "Colonel Moeller took his men round Talana Hill in a south-easterly direction, crossed the Vant's Drift road, captured several Boers, and saw the Boer ambulances retiring. Colonel Moeller, with the B Squadron of the Hussars, a Maxim, and mounted infantry, crossed the Dundee-Vryheid railway, and got near a big force of the enemy, who opened a hot fire, and Lieutenant M'Lachlan was hit.

"Colonel Moeller took his men round Talana Hill in a south-easterly direction, crossed the Vant's Drift road, captured several Boers, and saw the Boer ambulances retiring. Colonel Moeller, with the B Squadron of the Hussars, a Maxim, and mounted infantry, crossed the Dundee-Vryheid railway, and got near a big force of the enemy, who opened a hot fire, and Lieutenant M'Lachlan was hit.  Boers at Ladysmith "The cavalry retired across Vant's Drift, 1500 Boers following. Colonel Moeller held the ridge for some time, but the enemy enveloping his right, he ordered the force to fall back across the Spruit. The Maxim got fixed in a donga (water-hole). Lieutenant Cape was wounded, three of his detachment were killed, and the horses of Major Greville and Captain Pollok were shot.

Boers at Ladysmith "The cavalry retired across Vant's Drift, 1500 Boers following. Colonel Moeller held the ridge for some time, but the enemy enveloping his right, he ordered the force to fall back across the Spruit. The Maxim got fixed in a donga (water-hole). Lieutenant Cape was wounded, three of his detachment were killed, and the horses of Major Greville and Captain Pollok were shot.H!vvBL1H!YUizg~~_3.JPG) I dont really like A.I.P because I think they are wooden and really got the wrong size and the wrong bases. They look great if painted by Mike Blake but are really not for those with low painting skills. I think the best size for 54mm are the old herald or C.T.A "The force re-formed on a ridge north of the Sand Spruit, and held it for a short time. While Captain Hardy was attending to Lieutenant Crum, who was wounded, Colonel Moeller retired his force into a defile, apparently with the intention of returning to camp round the Impati Mountain, and was not seen afterwards."

I dont really like A.I.P because I think they are wooden and really got the wrong size and the wrong bases. They look great if painted by Mike Blake but are really not for those with low painting skills. I think the best size for 54mm are the old herald or C.T.A "The force re-formed on a ridge north of the Sand Spruit, and held it for a short time. While Captain Hardy was attending to Lieutenant Crum, who was wounded, Colonel Moeller retired his force into a defile, apparently with the intention of returning to camp round the Impati Mountain, and was not seen afterwards." The following list of casualties shows how hardly the glory of victories may be earned:—

The following list of casualties shows how hardly the glory of victories may be earned:—  boer from britains Divisional Staff.—General Sir William Penn Symons, mortally wounded in stomach; Colonel C. E. Beckett, A.A.G., seriously wounded, right shoulder; Major Frederick Hammersley, D.A.A.G., seriously wounded, leg. Brigade Staff.—Colonel John Sherston,[1] D.S.O., Brigade Major, killed; Captain [Pg 19]Frederick Lock Adam, Aide-de-Camp, seriously wounded, right shoulder. 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment.—Lieutenant B. de W. Weldon, wounded slightly, hand. 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers.—Second Lieutenant A. H. M. Hill, killed; Major W. P. Davison, wounded; Captain and Adjutant F. H. B. Connor, wounded (since dead); Captain M. J. W. Pike, wounded; Lieutenant C. C. Southey, wounded; Second Lieutenant M. B. C. Carbery, wounded dangerously, face and shoulder; Second Lieutenant H. C. W. Wortham, wounded severely, both thighs. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.—Captain George Anthony Weldon, killed; Captain Maurice Lowndes, wounded dangerously, left leg; Captain Atherstone Dibley, wounded dangerously, head; Lieutenant Charles Noel Perreau, wounded; Lieutenant Charles Jervis Genge, wounded (since dead). 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifles.—Killed: Lieutenant-Colonel R. H. Gunning,[2] Captain M. H. K. Pechell, Lieutenant J. Taylor, Lieutenant R. C. Barnett, Second Lieutenant N. J. Hambro.—Wounded: Major C. A. T. Boultbee, upper thigh, dangerously; Captain O. S. W. Nugent, Captain A. R. M. Stuart-Wortley, Lieutenant F. M. Crum, Lieutenant R. Johnstone, both thighs, severely; Second Lieutenant G. H. Martin, thigh and arm, severely. 18th Hussars.—Wounded: Second Lieutenant H. A. Cape, Second Lieutenant Albert C. M'Lachlan, Second Lieutenant E. H. Bayford.

boer from britains Divisional Staff.—General Sir William Penn Symons, mortally wounded in stomach; Colonel C. E. Beckett, A.A.G., seriously wounded, right shoulder; Major Frederick Hammersley, D.A.A.G., seriously wounded, leg. Brigade Staff.—Colonel John Sherston,[1] D.S.O., Brigade Major, killed; Captain [Pg 19]Frederick Lock Adam, Aide-de-Camp, seriously wounded, right shoulder. 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment.—Lieutenant B. de W. Weldon, wounded slightly, hand. 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers.—Second Lieutenant A. H. M. Hill, killed; Major W. P. Davison, wounded; Captain and Adjutant F. H. B. Connor, wounded (since dead); Captain M. J. W. Pike, wounded; Lieutenant C. C. Southey, wounded; Second Lieutenant M. B. C. Carbery, wounded dangerously, face and shoulder; Second Lieutenant H. C. W. Wortham, wounded severely, both thighs. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.—Captain George Anthony Weldon, killed; Captain Maurice Lowndes, wounded dangerously, left leg; Captain Atherstone Dibley, wounded dangerously, head; Lieutenant Charles Noel Perreau, wounded; Lieutenant Charles Jervis Genge, wounded (since dead). 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifles.—Killed: Lieutenant-Colonel R. H. Gunning,[2] Captain M. H. K. Pechell, Lieutenant J. Taylor, Lieutenant R. C. Barnett, Second Lieutenant N. J. Hambro.—Wounded: Major C. A. T. Boultbee, upper thigh, dangerously; Captain O. S. W. Nugent, Captain A. R. M. Stuart-Wortley, Lieutenant F. M. Crum, Lieutenant R. Johnstone, both thighs, severely; Second Lieutenant G. H. Martin, thigh and arm, severely. 18th Hussars.—Wounded: Second Lieutenant H. A. Cape, Second Lieutenant Albert C. M'Lachlan, Second Lieutenant E. H. Bayford.  irregular mins. I thought they were a good deal at 2.50 but the price now is a bit too much for some of the models. The Boer force engaged in this action was computed at 4000 men, of whom about 500 were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners. Three of their guns were left dismounted on Talana Hill, but there was no opportunity of bringing them away.

irregular mins. I thought they were a good deal at 2.50 but the price now is a bit too much for some of the models. The Boer force engaged in this action was computed at 4000 men, of whom about 500 were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners. Three of their guns were left dismounted on Talana Hill, but there was no opportunity of bringing them away. Maxim sold vast numbers of his guns to Russia. Russia soon went to war with Japan, and, Maxim proudly tells us, "more than half the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim Gun." Maxim was born in Maine in 1840. He was drawn to invention early in life. He worked with gas illumination, then electricity. He developed electric lighting systems even before Edison. In 1883 a friend told him, "Hang your electricity. If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!" Maxim took the advice. By 1885 he'd invented the first single-barrel machine gun. This "Maxim Gun" fired 666 rounds a minute, and it changed warfare. The Russo-Japanese War was a storm warning of the slaughter we'd see a decade later in WW-I. The Maxim Guns (and nastier guns that followed) made Maxim's name. They also gained him an English knighthood. By then he was an English citizen and a friend of royalty.

Maxim sold vast numbers of his guns to Russia. Russia soon went to war with Japan, and, Maxim proudly tells us, "more than half the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim Gun." Maxim was born in Maine in 1840. He was drawn to invention early in life. He worked with gas illumination, then electricity. He developed electric lighting systems even before Edison. In 1883 a friend told him, "Hang your electricity. If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!" Maxim took the advice. By 1885 he'd invented the first single-barrel machine gun. This "Maxim Gun" fired 666 rounds a minute, and it changed warfare. The Russo-Japanese War was a storm warning of the slaughter we'd see a decade later in WW-I. The Maxim Guns (and nastier guns that followed) made Maxim's name. They also gained him an English knighthood. By then he was an English citizen and a friend of royalty.

IMAGES OF DEATH Perhaps no event susceptible to being photographed has received more attention than war. Many groups have been interested in the camera's precise visual documentation of the people, places, and activities of warfare: military officers and decision makers in the field; political decision makers at home; opponents of war seeking visual proof of its horrors and inhumanity; ordinary citizens trying to visualize the places in which armies confront each other, and loved ones are fighting or have fought; and ex-combatants seeking mementoes of their comrades-in-arms, camps and equipment, and the people and landscapes encountered on campaigns far from home. When wars are over, societies seek visual means of commemorating the sites of heroic turning points or tragic loss. Artists fulfilled these needs entirely before 1839. Photography first supplemented, then in the 20th century largely replaced the artist as visual recorder of the preparations preceding combat, the fighting itself, and its horrific consequences for humans and their environment. From photography's beginnings, even when the bulky and cumbersome equipment needed for daguerreotypes, calotypes, and wet-plate photographs narrowly restricted photographers' movements in the field, photographic entrepreneurs were quick to seize opportunities to act either as independent operators or as official observers of military operations.

Artists fulfilled these needs entirely before 1839. Photography first supplemented, then in the 20th century largely replaced the artist as visual recorder of the preparations preceding combat, the fighting itself, and its horrific consequences for humans and their environment. From photography's beginnings, even when the bulky and cumbersome equipment needed for daguerreotypes, calotypes, and wet-plate photographs narrowly restricted photographers' movements in the field, photographic entrepreneurs were quick to seize opportunities to act either as independent operators or as official observers of military operations.  War photography went through several stages before 1920, corresponding roughly to advances in photographic technology. Before the wet-plate process was announced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, the earliest war photographs were daguerreotypes or calotypes which, with their long exposures, produced relatively static, staged photographs of men in uniform, landscapes, and buildings (whole or ruined).

War photography went through several stages before 1920, corresponding roughly to advances in photographic technology. Before the wet-plate process was announced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, the earliest war photographs were daguerreotypes or calotypes which, with their long exposures, produced relatively static, staged photographs of men in uniform, landscapes, and buildings (whole or ruined). Although it cut exposure times, the wet-plate process obliged photographers to carry both a darkroom or dark-tent and supplies of water and chemicals with them into the field. This meant in practice that subjects were still limited to static personnel, fortifications and other installations, and the human and material debris of battle. Notwithstanding the assumption that photography (unlike art) produced true images of reality, for aesthetic, practical, or propaganda reasons photographers could and did frame or stage the images they captured. Even after the advent of dry-plate technology c.1880 freed photographers from the need to process their pictures immediately, large-format cameras continued to make the best-quality negatives, requiring photographers to carry bulky tripods. Throughout the 19th century, therefore, the camera remained a ‘distant witness’.

Although it cut exposure times, the wet-plate process obliged photographers to carry both a darkroom or dark-tent and supplies of water and chemicals with them into the field. This meant in practice that subjects were still limited to static personnel, fortifications and other installations, and the human and material debris of battle. Notwithstanding the assumption that photography (unlike art) produced true images of reality, for aesthetic, practical, or propaganda reasons photographers could and did frame or stage the images they captured. Even after the advent of dry-plate technology c.1880 freed photographers from the need to process their pictures immediately, large-format cameras continued to make the best-quality negatives, requiring photographers to carry bulky tripods. Throughout the 19th century, therefore, the camera remained a ‘distant witness’.  The majority of war photographs taken before c.1900 did not reach broad audiences through publication, although many served as the basis for engravings published in popular journals such as Harpers Illustrated Weekly or the Illustrated London News. By the end of the 19th century, photographs could be reproduced in daily newspapers, and photographers began to function as war correspondents. War photographers attempted to support themselves by exhibiting in galleries, or publishing books of their photographs: commercial enterprises which ensured that the most repulsive images of carnage tended to be avoided.

The majority of war photographs taken before c.1900 did not reach broad audiences through publication, although many served as the basis for engravings published in popular journals such as Harpers Illustrated Weekly or the Illustrated London News. By the end of the 19th century, photographs could be reproduced in daily newspapers, and photographers began to function as war correspondents. War photographers attempted to support themselves by exhibiting in galleries, or publishing books of their photographs: commercial enterprises which ensured that the most repulsive images of carnage tended to be avoided.

boer war crowd in london

boer war crowd in london

Drawing by Charles J. de Lacia. From all accounts the two hostile columns numbered respectively 4000 and 9000 men, and against these forces Sir Penn Symons had at his command in all about 4000. Among these were the 13th, 67th, and 69th Field Batteries, the 18th Hussars, the Natal Mounted Volunteers,

Drawing by Charles J. de Lacia. From all accounts the two hostile columns numbered respectively 4000 and 9000 men, and against these forces Sir Penn Symons had at his command in all about 4000. Among these were the 13th, 67th, and 69th Field Batteries, the 18th Hussars, the Natal Mounted Volunteers, the 8th Battalion Leicester Regiment, the 1st King's Royal Rifles, the 2nd Dublin Fusiliers, and several companies of mounted infantry. But on the Dublin Fusiliers, the King's Royal Rifles, and the Royal Irish Fusiliers fell the brunt of the work, the task of capturing the Boer position, and the magnificent dash and courage with which the almost impossible feat was accomplished brought a thrill to the heart of all who had the good fortune to witness it.

the 8th Battalion Leicester Regiment, the 1st King's Royal Rifles, the 2nd Dublin Fusiliers, and several companies of mounted infantry. But on the Dublin Fusiliers, the King's Royal Rifles, and the Royal Irish Fusiliers fell the brunt of the work, the task of capturing the Boer position, and the magnificent dash and courage with which the almost impossible feat was accomplished brought a thrill to the heart of all who had the good fortune to witness it. Though the fight was a successful one, a grievous incident occurred. The 18th Hussars had received orders at 5.40 a.m. to get round the enemy's right flank and be ready to cut off his retreat. They were accompanied by a portion of the mounted infantry and a machine-gun. Making a wide turning movement, they gained the eastern side of Talana Hill and there halted, while two squadrons were sent in pursuit of the enemy.

foundry From that time, though firing was heard at intervals throughout the day, Colonel Moeller, with a squadron of the 18th Hussars and four sections of mounted infantry, was lost to sight. The rain had increased and the mist covered the hills, and it was believed that in course of time this missing party would return. But the belief was vain. In a few days it was discovered that they were made prisoners and had been removed to Pretoria. The following is a list of the gallant officers who were so unluckily captured:—

foundry From that time, though firing was heard at intervals throughout the day, Colonel Moeller, with a squadron of the 18th Hussars and four sections of mounted infantry, was lost to sight. The rain had increased and the mist covered the hills, and it was believed that in course of time this missing party would return. But the belief was vain. In a few days it was discovered that they were made prisoners and had been removed to Pretoria. The following is a list of the gallant officers who were so unluckily captured:—  fusiliers arch Dublin Colonel Moeller, 18th Hussars; Major Greville, 18th Hussars; Captain Pollok, 18th Hussars; Captain Lonsdale, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Le Mesurier, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Garvice, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Grimshaw, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Majendie, 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps; Lieutenant Shore, Army Veterinary Department, attached to 18th Hussars.

fusiliers arch Dublin Colonel Moeller, 18th Hussars; Major Greville, 18th Hussars; Captain Pollok, 18th Hussars; Captain Lonsdale, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Le Mesurier, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Garvice, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Grimshaw, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers; Lieutenant Majendie, 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps; Lieutenant Shore, Army Veterinary Department, attached to 18th Hussars.  An official account of the circumstances which led to the capture was supplied by Captain Hardy, R.A.M.C., who said: "After the battle, three squadrons of the 18th Hussars, with one Maxim, a company of the Dublin Fusiliers, a section of the 60th Rifles and Mounted Infantry, Colonel Moeller commanding, kept under cover of the ridge to the north of the camp, and at 6.30 moved down the Sand Spruit. On reaching the open the force was shelled by the enemy, but there were no casualties.

An official account of the circumstances which led to the capture was supplied by Captain Hardy, R.A.M.C., who said: "After the battle, three squadrons of the 18th Hussars, with one Maxim, a company of the Dublin Fusiliers, a section of the 60th Rifles and Mounted Infantry, Colonel Moeller commanding, kept under cover of the ridge to the north of the camp, and at 6.30 moved down the Sand Spruit. On reaching the open the force was shelled by the enemy, but there were no casualties. "Colonel Moeller took his men round Talana Hill in a south-easterly direction, crossed the Vant's Drift road, captured several Boers, and saw the Boer ambulances retiring. Colonel Moeller, with the B Squadron of the Hussars, a Maxim, and mounted infantry, crossed the Dundee-Vryheid railway, and got near a big force of the enemy, who opened a hot fire, and Lieutenant M'Lachlan was hit.

"Colonel Moeller took his men round Talana Hill in a south-easterly direction, crossed the Vant's Drift road, captured several Boers, and saw the Boer ambulances retiring. Colonel Moeller, with the B Squadron of the Hussars, a Maxim, and mounted infantry, crossed the Dundee-Vryheid railway, and got near a big force of the enemy, who opened a hot fire, and Lieutenant M'Lachlan was hit.  Boers at Ladysmith "The cavalry retired across Vant's Drift, 1500 Boers following. Colonel Moeller held the ridge for some time, but the enemy enveloping his right, he ordered the force to fall back across the Spruit. The Maxim got fixed in a donga (water-hole). Lieutenant Cape was wounded, three of his detachment were killed, and the horses of Major Greville and Captain Pollok were shot.

Boers at Ladysmith "The cavalry retired across Vant's Drift, 1500 Boers following. Colonel Moeller held the ridge for some time, but the enemy enveloping his right, he ordered the force to fall back across the Spruit. The Maxim got fixed in a donga (water-hole). Lieutenant Cape was wounded, three of his detachment were killed, and the horses of Major Greville and Captain Pollok were shot. The following list of casualties shows how hardly the glory of victories may be earned:—

The following list of casualties shows how hardly the glory of victories may be earned:—  boer from britains Divisional Staff.—General Sir William Penn Symons, mortally wounded in stomach; Colonel C. E. Beckett, A.A.G., seriously wounded, right shoulder; Major Frederick Hammersley, D.A.A.G., seriously wounded, leg. Brigade Staff.—Colonel John Sherston,[1] D.S.O., Brigade Major, killed; Captain [Pg 19]Frederick Lock Adam, Aide-de-Camp, seriously wounded, right shoulder. 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment.—Lieutenant B. de W. Weldon, wounded slightly, hand. 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers.—Second Lieutenant A. H. M. Hill, killed; Major W. P. Davison, wounded; Captain and Adjutant F. H. B. Connor, wounded (since dead); Captain M. J. W. Pike, wounded; Lieutenant C. C. Southey, wounded; Second Lieutenant M. B. C. Carbery, wounded dangerously, face and shoulder; Second Lieutenant H. C. W. Wortham, wounded severely, both thighs. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.—Captain George Anthony Weldon, killed; Captain Maurice Lowndes, wounded dangerously, left leg; Captain Atherstone Dibley, wounded dangerously, head; Lieutenant Charles Noel Perreau, wounded; Lieutenant Charles Jervis Genge, wounded (since dead). 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifles.—Killed: Lieutenant-Colonel R. H. Gunning,[2] Captain M. H. K. Pechell, Lieutenant J. Taylor, Lieutenant R. C. Barnett, Second Lieutenant N. J. Hambro.—Wounded: Major C. A. T. Boultbee, upper thigh, dangerously; Captain O. S. W. Nugent, Captain A. R. M. Stuart-Wortley, Lieutenant F. M. Crum, Lieutenant R. Johnstone, both thighs, severely; Second Lieutenant G. H. Martin, thigh and arm, severely. 18th Hussars.—Wounded: Second Lieutenant H. A. Cape, Second Lieutenant Albert C. M'Lachlan, Second Lieutenant E. H. Bayford.

boer from britains Divisional Staff.—General Sir William Penn Symons, mortally wounded in stomach; Colonel C. E. Beckett, A.A.G., seriously wounded, right shoulder; Major Frederick Hammersley, D.A.A.G., seriously wounded, leg. Brigade Staff.—Colonel John Sherston,[1] D.S.O., Brigade Major, killed; Captain [Pg 19]Frederick Lock Adam, Aide-de-Camp, seriously wounded, right shoulder. 1st Battalion Leicestershire Regiment.—Lieutenant B. de W. Weldon, wounded slightly, hand. 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers.—Second Lieutenant A. H. M. Hill, killed; Major W. P. Davison, wounded; Captain and Adjutant F. H. B. Connor, wounded (since dead); Captain M. J. W. Pike, wounded; Lieutenant C. C. Southey, wounded; Second Lieutenant M. B. C. Carbery, wounded dangerously, face and shoulder; Second Lieutenant H. C. W. Wortham, wounded severely, both thighs. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.—Captain George Anthony Weldon, killed; Captain Maurice Lowndes, wounded dangerously, left leg; Captain Atherstone Dibley, wounded dangerously, head; Lieutenant Charles Noel Perreau, wounded; Lieutenant Charles Jervis Genge, wounded (since dead). 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifles.—Killed: Lieutenant-Colonel R. H. Gunning,[2] Captain M. H. K. Pechell, Lieutenant J. Taylor, Lieutenant R. C. Barnett, Second Lieutenant N. J. Hambro.—Wounded: Major C. A. T. Boultbee, upper thigh, dangerously; Captain O. S. W. Nugent, Captain A. R. M. Stuart-Wortley, Lieutenant F. M. Crum, Lieutenant R. Johnstone, both thighs, severely; Second Lieutenant G. H. Martin, thigh and arm, severely. 18th Hussars.—Wounded: Second Lieutenant H. A. Cape, Second Lieutenant Albert C. M'Lachlan, Second Lieutenant E. H. Bayford.  irregular mins. I thought they were a good deal at 2.50 but the price now is a bit too much for some of the models. The Boer force engaged in this action was computed at 4000 men, of whom about 500 were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners. Three of their guns were left dismounted on Talana Hill, but there was no opportunity of bringing them away.

irregular mins. I thought they were a good deal at 2.50 but the price now is a bit too much for some of the models. The Boer force engaged in this action was computed at 4000 men, of whom about 500 were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners. Three of their guns were left dismounted on Talana Hill, but there was no opportunity of bringing them away. Maxim sold vast numbers of his guns to Russia. Russia soon went to war with Japan, and, Maxim proudly tells us, "more than half the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim Gun." Maxim was born in Maine in 1840. He was drawn to invention early in life. He worked with gas illumination, then electricity. He developed electric lighting systems even before Edison. In 1883 a friend told him, "Hang your electricity. If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!" Maxim took the advice. By 1885 he'd invented the first single-barrel machine gun. This "Maxim Gun" fired 666 rounds a minute, and it changed warfare. The Russo-Japanese War was a storm warning of the slaughter we'd see a decade later in WW-I. The Maxim Guns (and nastier guns that followed) made Maxim's name. They also gained him an English knighthood. By then he was an English citizen and a friend of royalty.

Maxim sold vast numbers of his guns to Russia. Russia soon went to war with Japan, and, Maxim proudly tells us, "more than half the Japanese killed in the late war were killed with the little Maxim Gun." Maxim was born in Maine in 1840. He was drawn to invention early in life. He worked with gas illumination, then electricity. He developed electric lighting systems even before Edison. In 1883 a friend told him, "Hang your electricity. If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!" Maxim took the advice. By 1885 he'd invented the first single-barrel machine gun. This "Maxim Gun" fired 666 rounds a minute, and it changed warfare. The Russo-Japanese War was a storm warning of the slaughter we'd see a decade later in WW-I. The Maxim Guns (and nastier guns that followed) made Maxim's name. They also gained him an English knighthood. By then he was an English citizen and a friend of royalty. you could use these cheap BMC to convert figures

Our own losses were severe, amounting to 10 officers and 31 non-commissioned officers and men killed, 20 officers and 165 non-commissioned officers and men wounded, and 9 officers and 211 non-commissioned officers and men missing. Though General Symons was known to be at the point of death, his promotion was speedily gazetted, and it was some consolation to feel that the gallant and popular officer lasted long enough to read of the recognition of his worth by an appreciative country. The following is an extract from the Gazette:— "The Queen has been pleased to approve of the promotion of Colonel (local Lieutenant-General) Sir W. P. Symons, K.C.B., commanding 4th Division Natal Field Force, to be Major-General, supernumerary to the establishment, for distinguished service in the field." An officer who was taken prisoner by the enemy, writing home soon after this engagement, made touching reference to some of the killed and wounded: "Poor Jack Sherston! Several of the officers here saw him lying dead on the hill at Dundee. When he left with the message entrusted to him he said to me, 'I shall never return.' Poor Captain Pechell! He had a bullet through the neck. General Symons was wounded and thrown from his horse, but he remounted and was conducted to the hospital, where he learnt that the height had been taken by our troops. His health improved a little, but he died on the following Tuesday. What a list of losses already! It is terrible to think that our own cannon were fired by mistake on our men, killing a large number. I saw M'Lachlan when he was wounded with a bullet in his leg. He went about on horseback saying that it did not hurt him, but at last he had to go to the hospital. My bugler, such a pleasant fellow, was hit in the head, the body, and the throat, and killed on the spot.... From a wounded officer, who is a prisoner, I hear that poor Cape had a bullet in the throat and another in the leg. He emptied his revolver twice before falling. He is progressing towards recovery.... He had the command of our Maxim gun which fell into the hands of the enemy. The entire detachment which worked the gun was killed or wounded. At that moment bullets were whistling all round us. Cape, I think, has been exchanged for one of the enemy's wounded. I suppose that he will be sent home invalided. I wonder what the future has in store for us? It is really heart-breaking to think that we are penned in here without being able to do anything but wait." IMAGES OF DEATH Perhaps no event susceptible to being photographed has received more attention than war. Many groups have been interested in the camera's precise visual documentation of the people, places, and activities of warfare: military officers and decision makers in the field; political decision makers at home; opponents of war seeking visual proof of its horrors and inhumanity; ordinary citizens trying to visualize the places in which armies confront each other, and loved ones are fighting or have fought; and ex-combatants seeking mementoes of their comrades-in-arms, camps and equipment, and the people and landscapes encountered on campaigns far from home. When wars are over, societies seek visual means of commemorating the sites of heroic turning points or tragic loss.

Artists fulfilled these needs entirely before 1839. Photography first supplemented, then in the 20th century largely replaced the artist as visual recorder of the preparations preceding combat, the fighting itself, and its horrific consequences for humans and their environment. From photography's beginnings, even when the bulky and cumbersome equipment needed for daguerreotypes, calotypes, and wet-plate photographs narrowly restricted photographers' movements in the field, photographic entrepreneurs were quick to seize opportunities to act either as independent operators or as official observers of military operations.

Artists fulfilled these needs entirely before 1839. Photography first supplemented, then in the 20th century largely replaced the artist as visual recorder of the preparations preceding combat, the fighting itself, and its horrific consequences for humans and their environment. From photography's beginnings, even when the bulky and cumbersome equipment needed for daguerreotypes, calotypes, and wet-plate photographs narrowly restricted photographers' movements in the field, photographic entrepreneurs were quick to seize opportunities to act either as independent operators or as official observers of military operations.  War photography went through several stages before 1920, corresponding roughly to advances in photographic technology. Before the wet-plate process was announced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, the earliest war photographs were daguerreotypes or calotypes which, with their long exposures, produced relatively static, staged photographs of men in uniform, landscapes, and buildings (whole or ruined).

War photography went through several stages before 1920, corresponding roughly to advances in photographic technology. Before the wet-plate process was announced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, the earliest war photographs were daguerreotypes or calotypes which, with their long exposures, produced relatively static, staged photographs of men in uniform, landscapes, and buildings (whole or ruined). Although it cut exposure times, the wet-plate process obliged photographers to carry both a darkroom or dark-tent and supplies of water and chemicals with them into the field. This meant in practice that subjects were still limited to static personnel, fortifications and other installations, and the human and material debris of battle. Notwithstanding the assumption that photography (unlike art) produced true images of reality, for aesthetic, practical, or propaganda reasons photographers could and did frame or stage the images they captured. Even after the advent of dry-plate technology c.1880 freed photographers from the need to process their pictures immediately, large-format cameras continued to make the best-quality negatives, requiring photographers to carry bulky tripods. Throughout the 19th century, therefore, the camera remained a ‘distant witness’.

Although it cut exposure times, the wet-plate process obliged photographers to carry both a darkroom or dark-tent and supplies of water and chemicals with them into the field. This meant in practice that subjects were still limited to static personnel, fortifications and other installations, and the human and material debris of battle. Notwithstanding the assumption that photography (unlike art) produced true images of reality, for aesthetic, practical, or propaganda reasons photographers could and did frame or stage the images they captured. Even after the advent of dry-plate technology c.1880 freed photographers from the need to process their pictures immediately, large-format cameras continued to make the best-quality negatives, requiring photographers to carry bulky tripods. Throughout the 19th century, therefore, the camera remained a ‘distant witness’.  The majority of war photographs taken before c.1900 did not reach broad audiences through publication, although many served as the basis for engravings published in popular journals such as Harpers Illustrated Weekly or the Illustrated London News. By the end of the 19th century, photographs could be reproduced in daily newspapers, and photographers began to function as war correspondents. War photographers attempted to support themselves by exhibiting in galleries, or publishing books of their photographs: commercial enterprises which ensured that the most repulsive images of carnage tended to be avoided.

The majority of war photographs taken before c.1900 did not reach broad audiences through publication, although many served as the basis for engravings published in popular journals such as Harpers Illustrated Weekly or the Illustrated London News. By the end of the 19th century, photographs could be reproduced in daily newspapers, and photographers began to function as war correspondents. War photographers attempted to support themselves by exhibiting in galleries, or publishing books of their photographs: commercial enterprises which ensured that the most repulsive images of carnage tended to be avoided.  boer war crowd in london

boer war crowd in london

No comments:

Post a Comment