German immigrants successfully established the town of Fredericksburg which they located in the southern borderland of Comancheria.

By the mid-1840s, after the immigrants had revolted from Mexican control and established the Republic of Texas, the white population around Fredericksburg had become so concentrated that they began to creep north of the Llano toward the San Saba hills, spurs of the Gaudalupe Mountains, to edge of the Great Plains. Later, when the Republic of Texas joined the Union as a state, the U. S. Army established Fort Mason in 1851 and the whites quickly established a settlement next to it and began to push their farms and ranches further north toward the San Saba River. In 1858, Mason County was established with the county seat located at Fort Mason.

By then, the resistance of the Comanches against the encroachment of the whites into their winter camp grounds began to rapidly crumble. de Anza's successes at stabilizing the New Mexico frontier, in the 1790's, was duplicated in Texas when a paramilitary force known as the "Texas Rangers" was established in the 1840s. Taking advantage of Colt's new "six-shooter," the rangers adopted the tactic of meeting the Indians' charge head-on; face to face with the Comanches, in a swirling mass of men and horses, the rangers could thumb the hammers of their pistols just as fast as the Comanches, hanging under the necks of their galloping horses, could loose arrows from their bowstrings.

The rangers quickly recognized, however, that disrupting Comanche war parties did not diminish the will of the Comanche clans to organize new excursions into Texas. Following de Anza's example in New Mexico, the rangers were soon attacking and killing Comanche women and children left alone in the encampments behind the Colorado while the warriors were marauding against settlements south of San Antonio. As the decade of the 1840s passed, the pressure of the rangers, compounded by the increasing numbers of white immigrants in Texas who brought with them American technology and the biological terror of epidemic diseases, relentlessly diminished the power of the Comanche to retain their control of their traditional hunting ranges.

In March 1840, the Comanche bands along the Colorado authorized their chiefs to propose to the government of the new Republic of Texas that a peace conference be held. The government invited the Comanche bands to San Antonio under a flag of truce. The government representatives demanded that, as a sign of good faith, the Comanche leaders bring to San Antonio all of the white women and children they had captured over the years and held as slaves. Expecting the negotiation over the white slaves to consume much time and ceremony, the Comanche war chiefs came to San Antonio with their families.

When the Comanche chiefs arrived in San Antonio, twenty lodges were set up in the plaza in the center of the small adobe town. The Comanches entered the plaza with one white captive, sixteen year old Matilda Lockhart. She and her three year old sister had been carried away two years earlier.

The Lockhart girl had been sexually assaulted by warriors and tortured by the Comanche women who held torches to her face and body; they had burnt off Lockhart's nose to the bone.(below milky way)

Lockhart told the Texans that many more white women and children were held captives by the bands in their encampments beyond San Antonio. When the peace conference opened in a building on the plaza, the Texans had determined to hold the Comanche chiefs hostage if they would not immediately release the captives. Mook-war-ruh, the chief chosen by the bands as their spokesman, began to explain the list of items the bands would accept in consideration for the release of the captives.

windows and others were attempting to enter the room, they began to chant the Comanche war hoop of rah, rah, rah. . . and scrambled to their feet, rushing at the soldiers crowding in the doorway. As the chiefs struggled to break through the doorway into the

windows and others were attempting to enter the room, they began to chant the Comanche war hoop of rah, rah, rah. . . and scrambled to their feet, rushing at the soldiers crowding in the doorway. As the chiefs struggled to break through the doorway into the  open, the soldiers discharged their muskets pointblank into their faces, while the chiefs released their bowstrings, driving the shafts of their arrows feather deep into the bodies of the soldiers.

open, the soldiers discharged their muskets pointblank into their faces, while the chiefs released their bowstrings, driving the shafts of their arrows feather deep into the bodies of the soldiers.

Fort Sill, north of Lawton, Oklahoma, the Lawton area was and is the center of Comanche territory.

The searchers

Ethan Edwards, returned from the Civil War to the Texas ranch of his brother, hopes to find a home with his family and to be near the woman he obviously but secretly loves. But a Comanche raid destroys these plans, and Ethan sets out, along with his 1/8 Indian nephew Martin, on a years-long journey to find the niece kidnapped by the Indians under Chief Scar. But as the quest goes on, Martin begins to realize that his uncle's hatred for the Indians is beginning to spill over onto his now-assimilated niece. Martin becomes uncertain whether Ethan plans to rescue Debbie...or kill her.

Millie Durkin/Durgan, who was taken in a raid when very young.The life story of Millie Durgan, who later became Mrs. Goombi when she married a Kiowa by that name, is quite unusual, in that she spent all her life, but the first year and half with the Kiowa, her captors. When she was 18 months old she was captured in a raid by the Kiowa, along with a sister and several Negro slaves, and taken north to the area that is now Oklahoma.In the fall of 1864, the Civil War was going on east of the Mississippi and the eastern part of now Oklahoma,, known as Indian Territory. Men from Texas were occupied with the war, many were away from home. The Kiowa and Comanche were roaming the plains. They had signed a treaty with the Confederate States to not attack the gray-clad soldiers, but were still roaming and raiding.A Comanche war Chief, Little Buffalo came to the Kiowa village near Rainy Mountain in the Wichita Mountains of southwestern Oklahoma. He held council with the Kiowa and persuaded them to go with him to raid the well protected settlements of Texas along the Brazos River. He stated there was much loot to have, because the Forts Belknap, Richardson, and other frontier army posts were almost deserted because of the war in the east. There was little to fear from the soldiers.The Kiowa were at first hesitant about joining because of the treaty with the Confederates, but the lure of the rewards of the raids soon persuaded them. The Comanche soon cinched the bargain by presenting the Kiowa with a genuine peace pipe, if they would join him. This was a strong argument, as a genuine peace pipe could only be obtained from the vacinity of the Pipe Stone Quarry in Souix Country in the Dakotas. Many lives had been lost by the plains Indians as they journeyed north for their pipes..

The school bells were ringing in the settlements along the Brazos when the 75 men of the raiding party headed south. They rode one horse and led another, changing off periodically, covering much distance in a day of hard riding, always ready for quick flight if there was too much resistance. They moved south, crossing the Red River about where BurkBurnett, TX  is now. On October 13, 1864, Little Buffalo and his band of raiders arrived at the point where Elm Creek empties into the Brazos.

is now. On October 13, 1864, Little Buffalo and his band of raiders arrived at the point where Elm Creek empties into the Brazos.

At the mouth of Elm Creek a part of the band, (they had divided into several groups probably planning to attack several farms and ranches at the same time) ran across Joel Myers and killed him. A mile and half away, another group attacked the Fitzpatrick Ranch, while the men were away. At home were Grandma Fitzpatrick, her daughter Susie Durgan, Susie’s 3 children, Lottie, Millie, and the baby, and Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s 15 year old son by another marriage, Joe Carter. The family was served by a negro family, Britt and Mary Johnson, who also had 3 children.

(they had divided into several groups probably planning to attack several farms and ranches at the same time) ran across Joel Myers and killed him. A mile and half away, another group attacked the Fitzpatrick Ranch, while the men were away. At home were Grandma Fitzpatrick, her daughter Susie Durgan, Susie’s 3 children, Lottie, Millie, and the baby, and Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s 15 year old son by another marriage, Joe Carter. The family was served by a negro family, Britt and Mary Johnson, who also had 3 children.

Grandma Fitzpatrick, (also known as Mrs. Clifton and Mrs. Carter, having been married 3 times) saw the Indians at a distance and got her family and the negro family into picket defense. Mrs. Fitzpatrick yelled at the Indians to not take her horses, but they ignored her and charged the picket fence.

Sue Durgan took her place at one point and Mary Johnson, armed with a flint gun, started firing as the Indians were breaking through the fence. Mary was doing great work with the gun and the Indians opened fire killing one of her sons, Jimmie, and Sue Durgan. Sue had hidden her little daughter Millie under the bed in the house. The Indians charged the house, taking anything of value, those still alive were taken prisoner, and the house was torched. As the house was blazing, one of the Indians returned to it as little Millie was crawling out from under the bed. The Indian that returned to the blazing house became Millie’s foster father.

AU-SOANT-SAI-MAH held her up before him, and could see her beautiful features, her gray, frightened eys and his sympathy and interest was aroused. He thought of his wife and decided to take the girl home. He held her in his arms, took her on his horse and cared for her on the long furious dash back to the Wichitas.

Taken captive at that time were Elizabeth Ann Anderson Carter Fitzpatrick; b. 3/29/1825, Charlotte (Lottie) Elizabeth Durkin, b. 9/7/1859, Millie Jane Durkin, b. 6/30/1862, and Mrs. Mary Johnson, her 3 children, Jube, Lottie and John. Within a year Elizabeth Ann and Charlotte Elizabeth were returned by the Kiowa. Charlotte had tribal tattos on her face and arms. Millie Jane was not returned.

Britt Johnson was instrumental in obtaining the release of the captives near where the town of Verden, OK is now. He traded food, blankets and other things for his wife and children, Mrs. Fitzpatrick and Lottie. Millie was kept secluded. The captives were then taken to Pauls Valley where the settlers and government officials helped them get home.

OK is now. He traded food, blankets and other things for his wife and children, Mrs. Fitzpatrick and Lottie. Millie was kept secluded. The captives were then taken to Pauls Valley where the settlers and government officials helped them get home.

Millie's foster father, a noted Kiowa warrior named AU-SOANT-SAI-MAH, was a partner of the famous chief, SET-ANKEAH (Sitting Bear) or SATANK, as he was known to white people. Both of these men were members of the Ko-eet-senko, which was a warrior society, composed of the ten bravest members of the tribe. AU-SOANT-SAI-MAH and his wife apparently had no other children than the foster child. It was customary that captives, especially Mexicans, led a rather hard life, and were not much better off than slaves.

Millie, however, happened to become the foster child of a couple who treated her better than usual. They were exceedingly fond of the little girl, and gave her the same consideration which she would have received if she had been of their own flesh and blood. The foster father was a man of considerable wealth in the tribe. AU-SOANT-SAI-MAH was a mighty hunter and brave in battle. AH-MATE was an excellent mother. The adopted child lived in comparative splender.

AU-SOANT-SAI-MAH had plenty of horses of the best stock, a good teepee, and fine clothing and weapons. Nothing was too good for his foster daughter. She always had a fine pony to ride and the best clothing to wear.

Millie's grandmother, her sister Lottie and the Negro slaves captured in the Elm Creek raid were all ransomed at Camp Napoleon, near the present town of Verden, in 1865. Millie, however, was not given up. Her foster father asked the other members of the tribe to promise to keep it a secret from the white people that the captive girl was still alive.

But, Millie was far from dead. Her identity as Millie Durgan was erased. One day her father asked a friend to name her. According to Kiowa custom, it was believed to be good medicine to name a child after some remarkable feat of valor. The Indian God-father thought for a long time. Finally he said: “Once when I was out in battle, I used up all my arrows except one, with a broken head. But, I used this arrow, shot my enemy and killed him. I suggest you name her SAIN-TOH-OODIE (Killed with Blunt Arrow), so Millie Durgan became SAIN-TOH-OODIE, the only name she ever had. Family names did not start until after the enrollment of the tribes started.

Millie grew up the daughter of wealthy, respected Kiowa. She always had the best of everything. This did not prevent her from learning all the domestic duties which an Indian woman had to know. She was taught as Indian children had always been taught. She could tan hides, she learned to make mocassins and clothing from the hides of the animals; cook meat just as her parents liked it best and was especially good at handling stock. She learned to ride and care for herself under all conditions.She learned to pack and unpack hurriedly as the Indians were swept from one section of the country to the other before the invading white men.

SAIN-TOH-OODIE married a young man named GOOMBI, who was one of the outstanding young men of the tribe and was from one of the best honored families. GOOMBI became a government scout and helped to trail the Cheyenne and other Indians who had raided during later years. He even led the soldiers against renegade Kiowa.

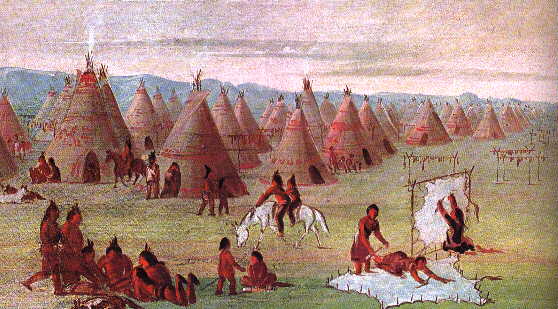

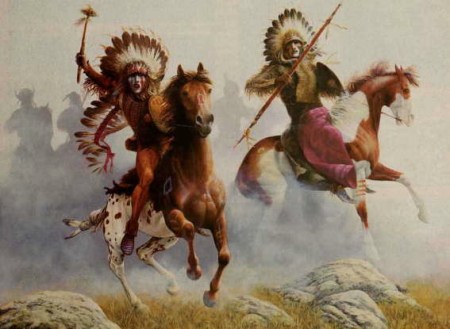

A Comanche War Party.

by collingwood

During the early days of the Texas Republic, the Comanche were the world’s best light cavalry. In fact, they were such fantastic fighters that the Spanish never even tried to subdue them, and the Comanche halted the expansion of settlements into the panhandle and northern Texas for nearly 50 years. Yet the Comanche today are a pitiful group, the defeated remnants of a terrible racial conflict.

Different races, especially aggressive ones, should not try to share the same territory.

Everywhere you go in Lawton, you see obese Indians. In Oklahoma each tribe has its own license plates, so you can tell a person’s tribe by watching him get into his car. (I tried to get a license plate that said “Comanche” but the DMV would not give me one.)

Sometimes it seems as though all the Comanche are unhealthy; the white man’s diet does not seem suited to a people adapted to living on game from the North American prairie.

When the Comanche get sick they go to the Public Health Service Indian Hospital at the eastern end of Lawton. If you drive by you are likely to see ancient Indians—poor and disheveled—holding out their thumbs for a ride. Their hands tremble.

It seems that the Comanche are as badly adapted to the white man’s economy as to his diet. I once watched a heavy Comanche woman slowly pushing pennies towards a white cashier. She carefully slid each coin across the counter as though it was very difficult to part with.

The Comanche’s misery is the result of their absolute defeat during a fierce conflict with whites in the 19th Century.

The Comanche War, as that conflict has come to be known, was lengthy and cruel. This terrible war that cursed both the Indians and the Americans was largely inherent in their circumstances; different races and cultures, especially aggressive ones, should not try to share the same territory.

early texas ranger pistol

early texas ranger pistolForming a part of the Eastern Shoshone linguistic group in southeastern Wyoming who moved on to the buffalo Plains around 1500 AD (based on glottochronological estimations), proto-Comanche groups split off and moved south some time before 1700 AD.

The Shoshone migration to the Great Plains was apparently triggered by the Little Ice Age, which allowed bison herds to grow in population.

It is not clear why the proto-Comanches broke away from the main Plains Shoshones and migrated south. That move may bave been inspired as much by the desire for Spanish horses released by the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 as by pressures from other groups drawn to the Plains by the changing environment.

The earliest known use of the term "Comanche" comes in 1706, when Comanches were reported to be preparing to attack far outlying Pueblo settlements in southern Colorado.The fact that the report matter-of-factly reported the coming attack—rather than as a new group—suggests that the residents, whether Pueblo or Spaniard, already knew the ethnonym by 1706 if not before.

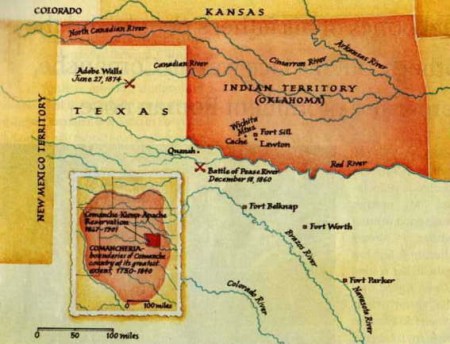

There were fewer than 8,000 Comanches in 1870. At the low point in 1920, the census listed fewer than 1,500. Currently, 5,000 Comanches live near their tribal headquarters in Lawton, Oklahoma. Total enrollment is around 8,000. Of the three million acres (12,000 km²) promised the Comanche, Kiowa and Kiowa Apache by treaty in 1867, only 235,000 acres (951 km²) have remained in native hands. Of this, 4,400 acres (18 km²) are owned by the tribe itself.

Always against us

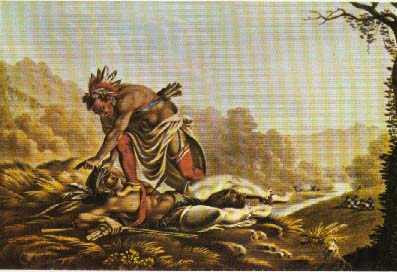

A brave takes a trophy.

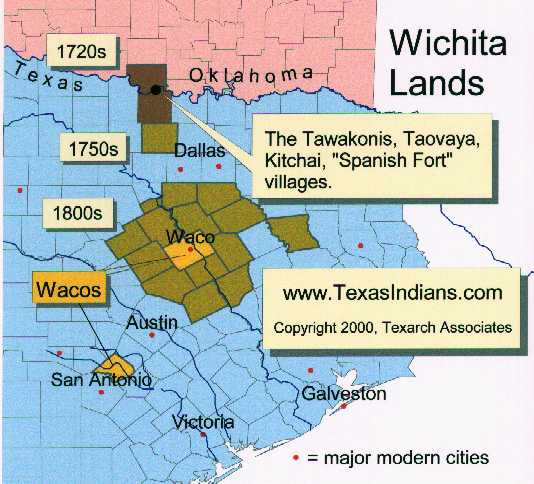

The name Comanche is a Spanish corruption of the Ute word Kohmahts, meaning enemy, stranger, or those who are always against us. Like many tribes, the Comanche called themselves simply “the people,” or Numunuh in their own language. They are an offshoot of the Shoshone, who hail from the area of today’s southern Idaho. Sometime during the 1500s, they left the mountain northwest and settled in southwest Oklahoma. There, they acquired horses from the Spanish, and began to dominate the high plains of western Oklahoma, the Texas Panhandle, and Eastern New Mexico. This vast territory was well watered and its grasslands fed the Comanche’s horses, endless herds of buffalo, and other smaller game. With the horse, the Comanche could travel rapidly on the planes, and easily kill buffalo.

In the mountain Northwest, the Comanche had been a poor, foot-bound people; with the horse they became lords of the western plains. Their population exploded. There was no census, but estimates of their numbers vary from 10 to 30 thousand. As they grew more powerful, they started raiding their neighbors. They raided the Apache and Pueblo in Arizona and New Mexico, and the Pawnee in Eastern Kansas. They traded with the Spaniards around Santa Fe but also raided settlements in Mexico and Texas. They often took captives in Mexico and ransomed them back to traders in Santa Fe for finished goods. Neither the Spanish Empire nor the Mexican Republic had the means to stop this well-organized piracy.

pueblo indian

Despite constant raiding, some time around 1790 the Comanche made a lasting alliance with the Kiowa. Like the Comanche, the Kiowa had come from the mountain Northwest, moved into the southern plains, and acquired the horse. The Kiowa and Comanche spoke different languages, but lived in a very similar manner. The Kiowa were a much smaller tribe, and perhaps they fitted into a special niche: not worth raiding and too small to be a threat, but useful allies. This alliance between two extremely warlike people held year after year. The two tribes raided together so consistently that Comanche raids were often Comanche-and-Kiowa raids.

rio grande

The Comanche came to the attention of Americans when Texas became free of Mexico. Shortly after independence, in 1838, the new republic signed its first peace treaty with the Comanche—a treaty that was probably doomed from the start. It was made with only one Comanche band, it did not define a boundary between Texas and Comanche lands, and it was never ratified by the Texas Senate. Essentially it required that the Comanche stop attacking whites—a not unreasonable demand—and some Comanche may have intended to abide by it. However, the Republic of Texas was a young, independent state with relatively wealthy white newcomers living in isolated settlements. They were irresistible targets for raiders, and the treaty was soon broken.

Comanche raids were striking examples of military precision and stealth. Raiding parties could number up to 1,500, and could move undetected across the grassland. Attacks on this scale had proven brilliantly successful against traditional Comanche targets: larger villages of mostly unarmed Mexicans or other Indians. These villages had no way to fight off the Comanche or pursue them as they retreated.

Raiders were most active during the full moon, when they could see at night. The waxing of the moon became a source of dread for Texas whites, who began to call the full moon a “Comanche moon.” When they sacked Texas farmhouses they usually killed the men and captured the youngsters and women. Comanche women often tortured and mutilated older girls and women to make them less attractive. The women also took the lead in torturing men. They might cut the skin off their feet, tie them to a horse, and make them walk behind until they collapsed and were dragged to death.

set of comanche moon

set of comanche moonTexas Governor Elisha Pease sends a small troop of Texas Rangers, under the leadership of Captain Inish Scull, to the Llano Estacado in pursuit of the celebrated Comanche horse thief, Kicking Wolf. This bold Indian steals Hector, Scull's famous horse, and takes it to the Sierra Perdida to give to the notorious Mexican bandit Ahumado, feared for the horrible tortures that he inflicts upon his victims. Scull, promoting McCrae and Call to Captains and instructing them to lead the Ranger troop back to Austin, sets off on foot after Kicking Wolf, accompanied only by the Kickapoo tracker Famous Shoes. Ahumado ties Kicking Wolf up to be dragged away by a horse, and takes Kicking Wolf's companion, Three Birds, prisoner. Ahumado intends to impose a slow death on Three Birds, but Three Birds throws himself off a cliff. Scull finds the unconscious Kicking Wolf being dragged by the horse, and cuts the Comanche's bonds, which allows Kicking Wolf to survive and return to his tribe. Scull is soon captured by Ahumado, and placed in a cage, where he is supposed to die slowly.

my conversion of a crescent cowboy, i made the colt in metal

Having returned to Austin, McCrae learns that his beloved Clara Forsythe intends to marry his rival, horse trader Bob Allen (though she is not married yet, as Scull's wife had led McCrae to believe). Call learns that his lover, the reluctant whore Maggie Tilton, is pregnant with his child. Prompted by Scull's insistent and promiscuous wife Inez, Governor Pease sends Call and McCrae out in charge of another typically small Ranger troop to rescue Captain Scull. While they are on this mission, Comanche chief Buffalo Hump leads his nation on the warpath. They burn much of Austin, killing Clara's parents and ravaging fellow Ranger Long Bill Coleman's wife, Pearl. Maggie, having been prepared by Call, hides under a smokehouse, thus escaping the Comanches' notice.

early pistol

early pistolThe Rangers turn back to Austin as soon as they hear of the raid there. Pearl and Long Bill are unable to recover emotionally, and Long Bill hangs himself.

Scull handles the cage so well that Ahumado has him taken down, and has his henchman Goyeto cut off his eyelids. Ahumado sends word to Austin that he will return Scull for a ransom of one thousand cattle. Governor Pease sends the Rangers out once again, to collect the cattle and exchange the herd for Scull. The Rangers go to Lonesome Dove in search of cattleman Captain King. Realizing they will not be able to even gather the cattle, let alone persuade King to sell them, Call and McCrae set out to try to rescue Scull on their own terms, leaving the rest of their troop behind. Meanwhile, Ahumado has been bitten by a brown recluse spider, and goes South to die. Call and McCrae find Scull going insane in a pit, but the rescue is soon enough to allow Scull to mostly recover. Scull returns to Austin and later becomes a general with the Union army. Because of the eyepieces he has devised, he becomes known as "Blinders" Scull.

Meanwhile, Buffalo Hump banishes his half-Mexican son Blue Duck. Blue Duck goes East and acquires wealth and notoriety as the leader of a gang of bandits.

At this point, the novel moves more quickly, giving highlights covering the period leading up to the sequel, Lonesome Dove. Maggie gives birth to Call's son Newt, but Call refuses to acknowledge the child is his. She goes to work at the general store, and Jake Spoon more or less moves in with her. The Civil War takes most of the soldiers away from the frontier, enabling the Comanches to push back the white settlers. After the Civil War, Call and McCrae are sent in pursuit of Blue Duck and his band of renegades. Buffalo Hump has gone off to die. Blue Duck hears of this and leaves his cutthroats to pursue his father. The Rangers attack his band, but Blue Duck, having left, evades capture. He finds his father at his chosen place of death and kills him there. Maggie dies while the Rangers are on this expedition.

By 1840, just two years after the treaty, relations between whites and Comanche were murderous and getting worse by the day. In March, the Texas government sent Colonel Henry W. Karnes at the head of a group to meet a delegation of Comanche chiefs at the San Antonio Council House. Karnes was charged with recovering Texas captives and trying to improve relations. The Texans estimated that the Comanche held some 200 captives, and promised that their return would be taken as a gesture of goodwill.

The meeting went badly. The Comanche arrived with only one of the promised captives, a young girl whose nose had been burned off. She was badly bruised from beatings, and said she had been repeatedly gang-raped. Texan soldiers, who were already angry over the raids and the broken treaty, killed the chiefs outright. Other whites opened fire on the Comanche who were outside the courthouse.

To the Comanche, the Council House slaughter was treachery of the lowest sort. What the Texans considered savagery—raiding, torture, and slaughter of captives—were to them the normal practices of war. From this mutual incomprehension, and from the slaughter of the chiefs, the seeds of long-term hatred were planted. The Comanche never forgave the Texans. Throughout the decades they were pillaging Texas, Comanche could have raided Kansas—it was no farther away than many parts of Texas—but they saved their wrath for Texas.

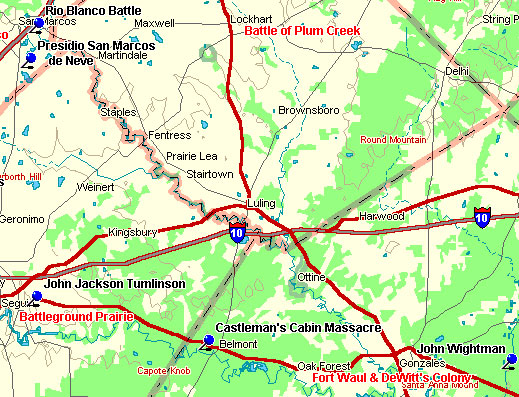

lockhart

lockhartThe Comanche did not wait long for revenge. In early August they launched a massive attack on the coastal towns of Victoria and Linnville. In Victoria, the local militia, often called “Minutemen,” managed to drive off the attackers. They fired from inside buildings, and the Comanche, unused to city fighting, retreated. At Linnville, the raiders killed some 20 residents; the others survived only by boarding ships and moving just off shore, where they watched as the Comanche burned the town to the ground. Linnville never rebuilt, and the area is now a residential part of Calhoun County.The raid which began in the Hill Country, consisted of a seizable group of warriors who swept down to the coast, attacking settlements along the way, including the seizable town of Victoria. Linnville was attacked on August 8th 1840. Many residents fled into the waters of the bay to escape death and after looting the warehouses in a search for guns, the Comanches returned the way they came. The Texas militia had formed while the Indians were at the coast and met them at Plum Creek (near present-day downtown Lockhart). The resulting Battle of Plum Creek stopped further incursions by the Comanches, who then retreated far from white settlements.

Linnville and Victoria are hundreds of miles from the center of Comanche territory in Oklahoma, and the attacks demonstrate the extraordinary reach and mobility the raiders enjoyed. At that time, the Comanche often hunted and camped in territory as far south as Austin. The barbed wire fence had yet to be invented, so there was little to stop them. Indeed, Texans had settled only the eastern and coastal parts of the state, so the coast was well within range of inland tribes.

The warfare that began with the council house killings and the revenge raids on Linnville and Victoria lasted until the late 1870s, and this nearly 40-year war can be divided into three stages. The first, which lasted until Texas joined the Union in 1845, pitted the Comanche against locally-organized whites supported by a Texas government that was highly sympathetic to them. The second, from 1845 until 1861, was much like the Cold War in that the federal government contained the Comanche but did not destroy their ability to make war. In the last stage of the conflict, after the Civil War, a vindictive Reconstruction government ignored bloody and repeated Comanche attacks on disarmed whites and supported the Comanche through a myriad of welfare and reform policies. Only after the post-Civil War elite was directly threatened did it take action, permanently ending the Comanche threat in 1879.

Texas President Mirabeau Lamar.

”. .....

Immediately after the great raids on Linnville and Victoria, the Texans called out the militia and assembled Ranger companies, and defeated the retreating Comanche force at the Battle of Plum Creek on August 14, 1840. The Comanche were slowed by the burden of their loot from Linnville, and also faced an enemy that was better armed and organized than their earlier Indian and Mexican antagonists. Since the 1830s, Texas Rangers had carried six-shooter revolvers as well as long rifles. The Comanche were still mostly armed with bows and arrows as well as lances, and usually retreated on their fast horses in the face of sustained gunfire. When the mounted Rangers could catch them, they would ride next to the Indians and inflict terrible losses with their six-shooters.

Another important ingredient in subsequent successes against the Comanche was the leadership of the dynamic and aggressive Texas president, Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar. Lamar was a Georgian who had moved to Texas to escape disappointments in his career and personal life. He fought at the Battle of San Jacinto, where the Mexican Army was defeated and Texas won independence. The Texas constitution allowed for a single presidential term in office, and Lamar was elected to succeed Sam Houston. One of the new president’s first challenges was the Comanche. As he put it, “The fierce and perfidious savages are waging upon our exposed and defenseless inhabitants, an un-provoked and cruel warfare, masacreing [sic] the women and children, and threatening the whole line of our unprotected borders with speedy desolation.”

After the victory at Plum Creek, Lamar began a policy of retaliatory raids on villages in the Comanche sanctuary in the Texas Panhandle and Oklahoma. Colonel John H. Moore, accompanied by Lipan Indian scouts, led the initial foray. The Rangers moved on an area that is now Colorado City, Texas, and the Lipans discovered a village with little security. Moore sent a detachment to cover a likely escape route, and ordered the main body of his command to attack. He caught the Comanche by surprise and killed 50 in the village. The ambush detachment killed another 80 retreating Indians. The killing was somewhat indiscriminate and included women and children. Moore’s tactics of attack and ambush were duplicated by the Rangers, and later, by the US cavalry. below a Texas Fort called Parker

(Interestingly, this was the same basic plan George Custer used at Little Big Horn in 1876. The difference was that the Sioux village was massive. The Indians also had lever-action rifles and pinned down the ambush detachment while sending a larger force to overwhelm the 7th Cavalry’s main attack. Custer never had a chance.) below fort parker

Lamar saw the conflict as a race war, and made no secret of his desire to rid the state of all Indian tribes. He probably would have exterminated the Comanche if he could have, but took different measures against less war-like tribes. His administration pointedly sent no aid when diseases swept through Indian territory. He began the process that moved the Cherokee, Caddo, and Tonkowa onto reservations in Oklahoma, but once they were settled peacefully, he never harried them.

Against the Comanche, Lamar developed both defensive and offensive strategies. The Rangers’ ability to defeat large groups prevented the Comanche from forming large raiding parties, and the Minutemen in the Texas settlements—almost like local crime watches—defended against smaller raids. The system was not perfect, but the raids became smaller and less frequent. Rangers also continued to maul Comanche villages. As T. R. Fehrenbach wrote in his definitive Comanche: A History of a People, there were many retaliatory actions “no one bothered to report

Part of the tragedy of the war is that although the Comanche had raided for generations, they had never faced an opponent like the Texans and did not understand them. Spaniards and Mexicans were disorganized prey, and could not mount a full-scale defense. Nor did they have a militia to call out. The Comanche assumed that white men were like themselves, loosely organized bands for whom an offence against one was not an insult to all. Texans saw things differently, and united against what they considered a threat to the entire state.

Until they took on the Texans, the Comanche had always been safe from reprisal raids, so for them, the war was over when the raiding party came home. The Texans were different. Months after a raid, they would surprise an offending—or completely innocent—Comanche village and put it to the torch. Also, Comanche movements were limited by the seasons and buffalo hunts, whereas the Texans could campaign any time of year. By the end of Lamar’s administration a generation of Comanche warriors was dead. T.R. Fehrenbach estimates that from 1838 to 1840, a quarter of the braves had been killed, most of them in the actions following the Council House fight.

What saved the Comanche and kept the war alive were larger questions of geopolitics. The Texans were going broke. The country’s finances were unsound, and the Comanche campaign was just one of several conflicts Lamar had to finance. There were constant Mexican incursions, and Lamar even sent troops into Mexico at great expense.

The Comanche called themselves "The People." Others usually referred to them as their enemies, "Those who always fight us." A single generation of warriors at the turn of the eighteenth century managed to acquire and master not just the horse, but the art of horse raising and more importantly, horseback fighting. The Comanche Nation held the center of this map and dominated, virtually owned, everything and body around it.

As possession of horses became a signifier of status, Comanche men loathed walking anywhere. When a warrior desired to go somewhere, a wife brought his horse right to his teepee's entrance. Boys were placed on horseback before they could walk, and they could catch and saddle their own ponies by the time they were five. Through the next century, the Comanches effectively owned the hunting grounds, fields and people abutting their buffalo range. Their serfs were expected to provide them with gifts and supplies, including manpower in time of war.

Colonel Dodge observed, some years after his 1833 encounter with a large band of Comanche in the Wichita Mountains, that "the Comanche were not only the best horse thieves, but the best horse breeders in America." The band treated Dodge and his dragoons in an aloof and indifferent manner but they showed an acute interest in the army's heavy horses. They preferred paints and emphasized strains that would produce better traveling, hunting or war ponies. The Comanche didn't steal Dodge's horses though the heavy strain would surely breed in distance and comfort. They learned through a century of dealing with foreign nations that new generals and their armies would soon return with horses and weapons as tribute for an alliance. Comanches parents were exceptionally kind and loving to their children. So tenderhearted in fact that grandfathers or uncles assumed the responsibility for the young boy's rigorous martial training. Some legends proclaim that the most promising young warriors attended leadership school. A woman served as commandant at a camp established for this purpose and prominent war chiefs visited, lecturing the boys on weapons, communications and tactics. Texas Ranger Noah Smithwick was appointed Texas Comanche agent and spent a considerable amount of time living with the tribe in the late 1830s. He noted the boys were constantly engaged in contests that developed their riding, hunting and fighting skills. Simulating a hunt, young warriors would sometimes pursue a young buffalo bull. "The hunters would begin by shooting arrows into the animal's hump. When it became infuriated and charged one of them, another would gallop beside it and jerk an arrow from its hump. At the fresh pain the bull would turn and attack its new tormentor. It was then that a well-trained horse was essential. Smithwick recorded seeing old bulls whirl so quickly that it was 'all the Indian's pony could do to get out of the way.' But then another warrior would race in and snatch an arrow, and the bull would turn on him. The hunters would keep this up until the animal was exhausted, when they would dispatch it and retrieve their arrows." Just as horses trained for the hunt knew to turn away at the sound of a bow twang to avoid possible goring, war ponies were trained to respond to the lightest touch of the knee or foot. The warriors tied a rope around the horse's neck with a loop on the opposite end which held his ankle. On approaching the enemy, the Comanche could lean over the side of his horse at a full run, firing from underneath the horse's neck while using the animal's body as a shield. These skills gave the Comanche a tremendous advantage on the battlefield, forcing their opponents to take a defensive position and dismount in order to fire accurately. Contrary to the movies, only the Comanche tribe attacked on horseback in battle.The average mounted Comanche warrior could circle a modern-day football field at a full run while accurately shooting twenty arrows at targets on the opposite side of the field, and this was done in the time it took to reload a gun. They usually attacked in concurrent circles of five to eight warriors. The circles were coordinated through a complicated communication system involving oral commands as well as hand and mirror signals. They swarmed their enemy, alternating between arrows, lances and short arms (guns, swords, and tomahawks) depending on the range.The Comanche needed markets to sell stolen horses and captives. In early 1720 when they found they were unwelcome at the trade fair at Taos, they took this opportunity to show the New Mexicans their version of a hard bargain. They grabbed a number of local citizens, and in plain view of their former trading partners began torturing and killing. Every cry drove home their bargaining points until their "shopping" privileges were reestablished. The tribe recognized the value of terror and took every opportunity to exhibit cruelty, establishing fear in the hearts of their opponents.

As the power and influence of the Comanche rapidly increased, they were not content to take away the Apaches brief control of the Plains horse trade. The Comanches doggedly pursued their enemy, eventually resulting in the 1750s attack on the Spanish mission at San Saba, which had become a sanctuary to the Lipan Apache. The massacre at their little outlying mission caused the Spanish to retaliate with a punitive force of five hundred. The army marched to the Red River where they found the Old Spanish Fort defended by more than a thousand Comanche and Wichita warriors, as well as French soldiers. The Spanish troops were easily routed, abandoning much of their armor and weapons, including two cannons, in their panicked retreat down the Grand Prairie toward their barracks in San Antonio. The Spanish realized they had waited too long to conquer the Plains and resigned to farming and tending their herds under armed guards in their South Texas colonies. Through the next century, the Comanches effectively owned the hunting grounds, fields and people abutting their buffalo range. Their serfs were expected to provide them with gifts and supplies, including manpower in time of war.

The Comanche Nation

The United States was receptive to annexation, so Texas joined the Union in 1845. The expensive Ranger companies were cut back and federal troops took over their job. At first, the Army sent only infantry to forts along the frontier, and they could not stop the Comanche from moving freely over the prairies. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis formed a cavalry regiment to send to Texas, which managed to prevent some raiding. Its efforts were helped by a cholera epidemic the “Forty-niners” brought when they crossed the plains during the Gold Rush. It is estimated that the Comanche population dropped from 20,000 to 12,000 during this time.

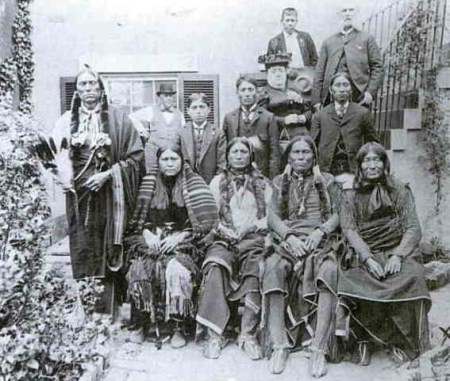

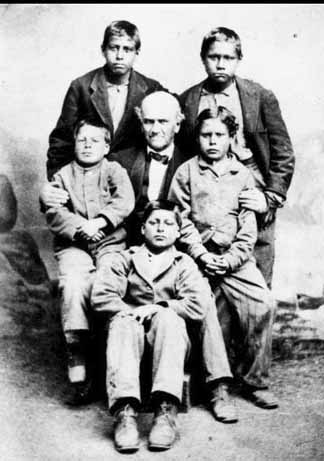

Quaker Tatum with some of his charges.

The do gooding of Tatum is still with us today, think no further than monsters like Hillary Clinton and ones like her, big mouthed tarts and rich with it and nothing to do, the reason of life for a lot of these is giving to charity, they never realise that charity is just the carrot in front of the Donkey's nose and the whole thing is like a viscous circle disappearing up its own arse then reappearing even more shitty than before.The Victorian sense of guilt thats still with us has a lot to answer for but guess what its the working class who always pick up the bill.

Whites began to push the internal Texas frontier forward. The east and south were settled by then, but the north and west—where Wichita Falls and Amarillo are today—were still raw frontier. With the Comanche more or less under control, white settlers began to fill the empty parts of the state.

By 1860, the Comanche were on the defensive—reduced by plague and harried by the US Cavalry. Their final defeat would have been just a matter of time, but the Civil War changed the balance of power. The federal troops left, and Confederate forces went East. The pressure lifted, and midway through the war the Comanche started raiding again. They went back to their old ways of rape, plunder, and torture, but with a new twist. They soon found they could steal Texas cattle and trade them with Comancheros—Hispanic traders in the Rio Grande Valley—for lever-action rifles. The Texans lost the advantage in firepower they had always enjoyed. The Comanche had always been able to get a few modern weapons, but massive industrial production and increasing trade made them much easier to get.

The Texas Reconstruction government therefore inherited a new Comanche war that was blowing with a terrible fury, but did not take it seriously. The carpetbag elite was less interested in fighting Indians than in enriching itself at local expense and supporting the newly freed blacks. Things only got worse as the 1860s wore on, and T.R. Fehrenbach writes that by 1870, “long-settled regions were regressing toward depopulation. Only hundreds of settlers were being killed, but meanwhile thousands were deserting the frontier. The panic was very real.” The frontier retreated—an early form of white flight—as farmers left their properties for safer areas. Those who stayed behind turned their haciendas into fortresses. The effect was to hold back growth; the panhandle could not be settled until the 1880s. Lyndon Baines Johnson’s ancestors were among those the Comanche harried.

Even as the Comanche were murdering white homesteaders, the government attempted a sanctuary, welfare buy-off, faith-based assimilation program that is reminiscent of modern times. During the final Comanche War from 1865 to 1879, Texas whites were disarmed by the Reconstruction government, and prevented by law from retaliatory raiding into Comanche territory. They could do little more than lobby a hostile occupation government for aid—not always to much effect. Pro-Indian liberals in government as well as East Coast sentimentalists even prevented several murderous Indian chiefs from being hanged. Ironically, the attack those chiefs led was the very incident that caused the Army and federal government finally to act decisively.

More humane policy

One of the causes of federal inaction was a genuine desire to handle Indian troubles in a humane way. East of the Mississippi, Indian wars had been bloody affairs that ended with the Indians absolutely destroyed or confined. If anything, Northerners were slightly more violent than Southerners.

Yankees tended to wipe out Indians and remove any survivors to small, out of-the-way reservations. In upstate New York, the Continental Army destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages and left survivors to starve or seek aid from the British. In 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, American troops defeated an Indian force and then removed all remaining Indians from Ohio. After victories in the Midwest, whites paid the surviving Indians paltry sums for their land and sent them West with essentially no support. Abraham Lincoln’s sole experience as a soldier was a brief period of garrison duty with the Illinois Militia in the otherwise bloody Blackhawk War, in which the Sac and Fox Indians were destroyed and forced out of Illinois and Wisconsin.

Big Tree: sentenced to death but not executed.

In the South, the Cherokee were the source of the longest-running conflict, and held lands in Georgia long after the northeastern states had destroyed their Indians. As tensions with whites mounted, relocation became the favored solution rather than war and ad hoc expulsion, and was carried out mainly though an admittedly one-sided legal process. Cherokee removal was a relatively peaceful and fair solution to two incompatible peoples living close to each other with a long history of violence. Stand Watie, a Cherokee chief who later became a Confederate general, supported the move from Georgia to Oklahoma, and brought his band West well before the now-notorious “Trail of Tears.”

In that context it is understandable that after the Civil War, many pressure groups in the East, no longer threatened by Indians, pushed for more peaceful measures. Also backing the changes was the Office of Indian Affairs, which wanted more control over Indians at the expense of the Army. President Grant therefore tried to treat Indians as wards of government rather than independent nations, and to assimilate and civilize them rather than destroy them.

In the past, Indian wars were often sparked when a dishonest Indian Agent stole government aid to the Indians for his own profit, so in 1869, Grant charged religious groups with carrying out his new policy of turning Indians into peaceful farmers. The denomination that got the Comanche assignment was the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Quakers are one of America’s oldest and most influential founding groups. They live a life of piety and thrift, and disavow fancy dress and military action, but it may have been a mistake to pick a group religiously opposed to war in any form.

President Grant’s agent to the Comanche was Lawrie Tatum of Iowa, who had probably never seen an Indian before he answered his Church’s call and headed West. Tatum arrived at Fort Sill in 1869 and enacted a sort of Great Society program. He started schools, gave deeds of farmland to the Comanche with instructions for farming, and established a mill for grinding grain. The Comanche also got free coffee, sugar, and blankets, and lived in safety. Soldiers secured Fort Sill and the agent’s supplies, but did not interfere with Comanche activity or take to the field. Quakers would not use the military to keep the Comanche on their reservation and avoid war.

Ta-wáh-que-nah, Mountain of Rocks, Second Chief of the Tribe. Comanche

Tatum worked hard to teach the Comanche to be civilized farmers but was defeated by circumstances. The Comanche culture’s central focus was on warfare and raiding. Wealth and status could only be acquired through war, and Quaker pacifism was too foreign to graft onto their way of life.

Also, welfare handouts are always unsatisfying. The Comanche were not happy with reservation rations and it was far more rewarding to plunder Texans. The Fort Sill Reservation became a sanctuary from which they could wage war. In 1871 there were even scalpings within a short distance of Army posts. Whites had sent a capable and honest agent to deal with the Comanche and bring about peace, but the Comanche were not willing to be peaceful.

Sherman and the Comanche

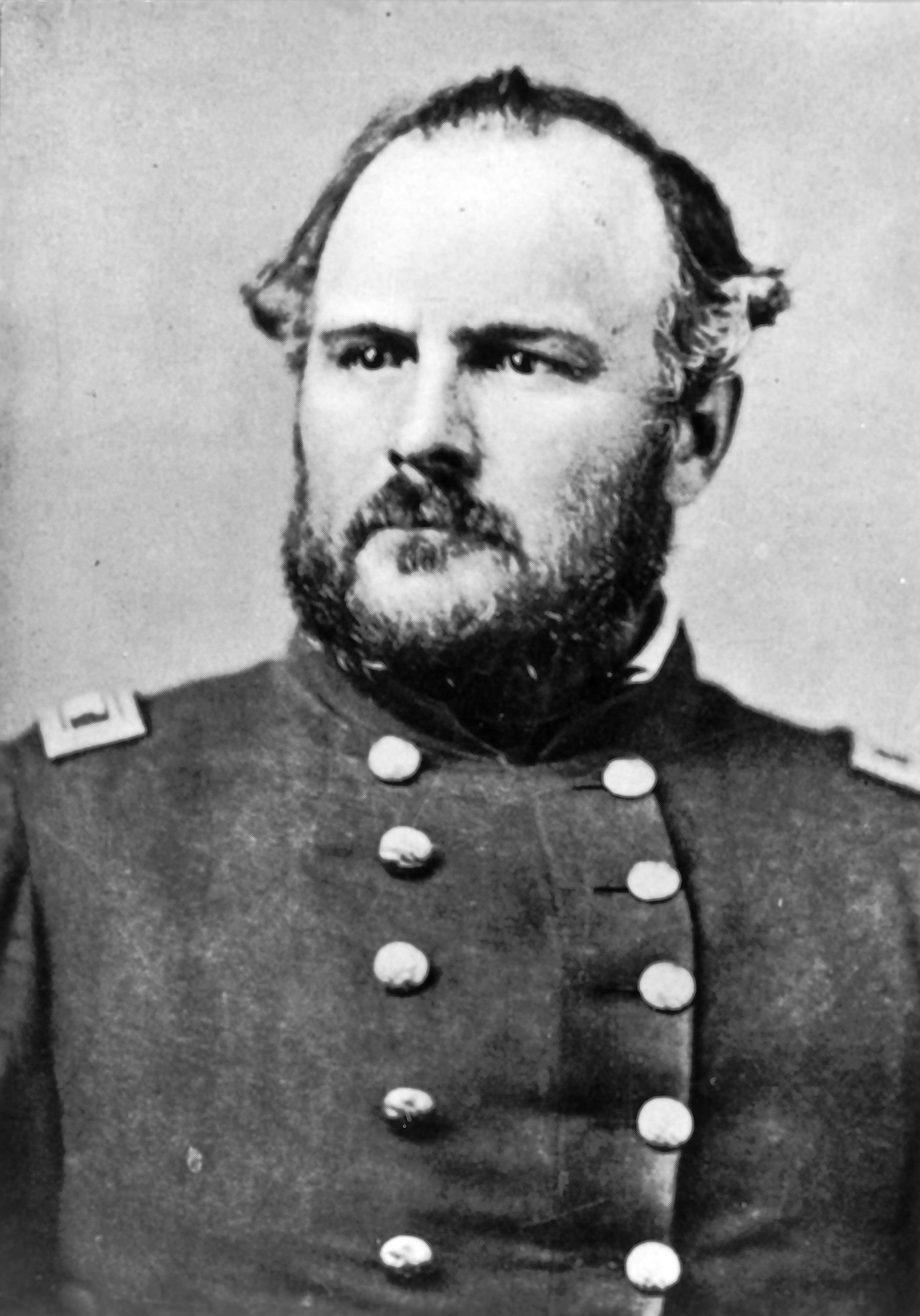

Ronald Mackenzie, scourge of the Comanche.

Just as it is today, it was whites who lived furthest from the menace who were convinced they knew best how to handle it. In Philadelphia or New York it was easy to talk about humane Indian policies, but on the frontier, whether in Confederate or Yankee territory, sentiments were different. In Minnesota in 1862, Sioux Indians attacked whites, killing hundreds. Many whites were fresh from northern Europe or descended from the very liberal Puritan and Quaker colonists. Yet they rallied and pushed the Sioux out of the state.

In Colorado in 1864, Methodist minister and volunteer army officer John Chivington, a fervent abolitionist, led a force of mostly settler militia against a group of Cheyenne after a series of murderous raids. His militia massacred Indians without compunction but his force also included a few regulars from the East who were appalled by the killing and raised a stink. Chivington also made a bad mistake: He attacked a peaceful band of Indians, not the hostile Dog Soldiers, an out-of-control offshoot of the Cheyenne, who were actually doing the raiding.

He was a Woodsman, itinerant preacher, abolitionist, and commander, John Milton Chivington’s story is a tale of enormous ego and ambition, of a thirst for glory, of secret schemes to destroy his rivals.

He was a Woodsman, itinerant preacher, abolitionist, and commander, John Milton Chivington’s story is a tale of enormous ego and ambition, of a thirst for glory, of secret schemes to destroy his rivals.In his less than three years as Colorado’s military commander, Colonel Chivington’s political maneuvering created sworn enemies of all his peers, including Lt. Col. Sam Tappan, Colonel John Slough, and Colonel Jesse Leavenworth. For a time, he enjoyed extreme loyalty from some of his junior officers, including Major Wynkoop and Captain Soule, but that ended bitterly with his actions at Sand Creek.

Later, he came under suspicion for the assassination of Silas Soule and James Cannon.

Also in 1864 an Army unit under Kit Carson fought the Comanche at the Battle of Adobe Walls, in Hutchinson County, Texas. The Indians surrounded the force but were held off with two mountain howitzers. The cannon were decisive. Carson’s men were outnumbered nearly ten to one, but killed nearly 100 Indians for a loss of six whites.

Texans therefore eventually got help from people who knew Indians first hand. Help arrived, ironically, in the form of William T. Sherman, who never had much faith in Grant’s Indian policy. In 1871 he toured Texas to inspect damage from Comanche raids, and had a near encounter with Indians that had an effect on policy. A group of braves led by Set-tainte, Set-tank, and Big Tree attacked a wagon convoy of Army supplies that passed just minutes behind Sherman’s lightly guarded inspection tour. The dozen men on the convoy fought back, but seven were killed, scalped, and mutilated. One man died after being tied upside down to a wagon wheel with a fire set under his head.

Sherman was shaken by this close call, and sent out the cavalry under Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie to investigate. With information from Agent Tatum, Mackenzie cornered the three ringleaders. Set-tank died resisting arrest, but the other two were sent back to Texas for trial.

Comanche knew better than to charge these.

romeo 54mm

romeo 54mmSet-tainte and Big Tree were sentenced to death, but not executed. The trial became a circus, with the two Indians at the center of a political struggle they must have found bewildering. As T.R Fehrenbach explains, “There was much popular sentiment in the East against hanging the aborigines; more important, the Indian Bureau and Department of the Interior strongly resented the army’s interference in Indian affairs.” President Grant wired the Reconstruction governor Edmond J. Davis and asked him to commute the sentences to life in prison. Davis did so. Eventually the two were released after serving less than a year. Texans were outraged. Even Quaker Tatum, who by this time was thoroughly disillusioned with the peace policy, was indignant.

romeo 54mm

Although President Grant had pushed for a pardon, he reconsidered the peace policy and quietly let Colonel Mackenzie take the field. Mackenzie brought along Gatling guns, which gave his men a real edge over larger forces. (Rapid-fire weapons were rarely used against mass charges of Indians—they were too smart to try that—but having them meant Mackenzie’s men rarely had to face such charges. Things might have turned out differently for Custer if he had taken Gatling guns.)

Quanah Parker, one of the last Comanche war chiefs.

Mackenzie drove ruthlessly into Comanche territory. He was a hard man, who pursued Indians wherever they fled—even into Mexico—and his men certainly killed women and children. One of his harshest tactics was to capture any Indians he could—women, children, elders—and hold them hostage. This meant Comanche war parties were forced to move with their entire villages, lest their families wind up in prison camp or dead from a trigger-happy trooper. The Comanche had even more to fear from the militia. Local men who may have known people killed in raids were invariably more vengeful than professional soldiers.

This policy of interning non-combatant Indians was part of one of the last full-scale campaigns against the Comanche, starting in August 1874, when Mackenzie pursued a force led by Chief Quanah Parker into the Llano Estacado of the Southern Plains.

In late September, Mackenzie’s men captured a New Mexican Comanchero trader and made him talk by stretching him over a wagon wheel. He revealed the location of a large Comanche village in a canyon. Mackenzie’s men rode all night and stormed the canyon, capturing the horses, food stores, and teepees. The braves, always excellent fighters, held off the army until the women and children climbed out of the canyon, but Mackenzie burned their supplies and killed their horses. Over the next several days, he pursued and defeated the hungry, foot-bound Comanche. Many braves surrendered and returned to the reservation.

romeo models

romeo modelsThese tactics greatly reduced the Indian menace by the end of 1875, but the Comanche faced yet another threat. The expanding railroads brought whites armed with new buffalo guns onto the prairie to hunt the buffalo for their skins. The result was a slaughter that nearly wiped out the great herds on which the Comanche had depended for generations. The hunters themselves were dangerous; one group defeated a larger force of Comanche with their excellent rifles in 1874, at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. Constantly pursued by the Army, starving for want of game, by 1879 the Comanche were a beaten people and never again threatened Texas. From a possible high of 30,000 at the start of the 19th century, the Comanche were reduced to roughly 1,500 by 1878. A once-proud people finally submitted permanently to the reservation.

Buffalo hunters: another deadly enemy of the Comanche.

The Comanche War is now history, its many tales preserved in movies and books. No Texan now living ever feared a Comanche moon. Today, tribal conflict takes different forms, and it is incursions from the South that are pushing back the white frontier. Clashes are not so sharp as those in the 19th century, but the outcome is no different. The destiny of Texas is being decided through immigration and demographics rather than armed conflict, but the questions remain the same: who will populate and who will rule? Earlier Americans understood what was at stake; today’s Americans have been numbed into acquiescence.

Duncan Hengest served as a company-grade field artillery officer in the United States, Korea, and Iraq. He can be reached at d.hengest@yahoo.com.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Only Good Indian …

Many people think Sherman said that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” but he always denied it. It may well be that the phrase expressed his true sentiments, however, since he waged harsh war on Indians, allowed diseases to take their course among them, and encouraged the slaughter of the buffalo on which the Indians depended.

Congressman Cavanaugh.

The originator of the phrase seems to have been Montana Congressman James Michael Cavanaugh (1823-1879), who opposed Grant’s Indian policy. He was originally from Massachusetts, but made a career as a lawyer/pioneer in Minnesota, Colorado, and Montana at the height of the Indian troubles. He made the following remarks during a debate on an Indian Appropriation Bill that took place on May 28, 1868, in the House of Representatives:

“I will say frankly that, in my judgment, the entire Indian policy of the country is wrong from its very inception. In the first place you offer a premium for rascality by paying a beggarly pittance to your Indian agents. The gentleman from Massachusetts [Congressman and former General Ben Butler] may denounce the sentiment as atrocious, but I will say that I like an Indian better dead than living. I have never in my life seen a good Indian (and I have seen thousands) except when I have seen a dead Indian. I believe in the Indian policy pursued by New England in years long gone. I believe in the Indian policy which was taught by the great chieftain of Massachusetts, Miles Standish [who was criticized by contemporaries for harsh treatment of Indians]. I believe in the policy that exterminates the Indians, drives them outside the boundaries of civilization, because you cannot civilize them. Gentlemen may call this very harsh language, but perhaps they would not think so if they had had my experience in Minnesota and Colorado. …

“My friend from Massachusetts has never passed the barrier of the frontier. All he knows about Indians (the gentleman will pardon me for saying it) may have been gathered I presume from the brilliant pages of the author of The Last of the Mohicans or from the lines of the poet Longfellow in “Hiawatha.” The gentleman has never yet seen the Indian upon the war-path. He has never been chased, as I have been, by these red devils—who seem to be the pets of Eastern philanthropists.”

largest most horrible raid ever

made by Indians upon Texas, which resulted in the famous battle of "Plum Creek." A large

band of Comanches under the notorious chieftain "Buffalo Hump" took possession of Victoria,

then came on down Peach Creek, through a sparsely settled country, burning houses and

killing until they came to Lynnville. They were supposed to have been guided by Mexicans.

On their way they came upon Mr. Foaly and Parson Ponten, who were going across the country

to Gonzales. Foaly was riding a very fine race horse, while Mr. Ponten's animal was old

and slow. They saw the Indians, about a quarter of a mile off and whirled to run. The

race horse soon bore Foaly far in advance of Ponten, who was fast losing ground. The

first Indian swept past him without even turning his head. Foaly on the race horse

was evidently the prize upon which he was bending every energy. The second Indian came

on, and in passing, struck him on the head with his spear-he too, intent upon over taking

Foaly. A third as he came, drew his bow, and shot, the arrow striking his leather belt

with such force as to knock him from his horse, where he lay as if dead, but pondering

whether or not he should shoot, his double barreled shotgun being still at his side.

He wisely concluded to be still and the rest of the Indians passed him without a pause,

doubtless thinking him dead. As soon as the last one had gone by, he sprang up and crawled

into a thicket and there lay hid until they came on back with Foaly who made a brave run

but was caught at last. They chased him (Foaly) to a little creek, where they hemmed him

and as a last resort, he dismounted and tried to hide in a water hole. From the signs

they roped and dragged him out, and brought him on to the spot where they had left Ponten,

seemingly dead. Finding him gone, they made Foaly call him, but of course no answer came.

The cruel wretches then shot and scalped Foaly, and it was that when found, the bottoms of

his feet had been cut off and he seemed to have walked some distance upon the raw stumps.

Ah! The cruelty of those Comanche warriors knew no bounds. The Rev. Mr. Ponten himself

gave me an account of this race, and its attendant particulars, and I think I can couch

for its truth. At Lynnville they burned a few houses, killed a few more citizens and

then went on unmolested. They took two captives, Mrs. Crosby and Mrs. Walters whose

husbands were killed in the fight, and started back on their incoming trail. It is

strange, but true that all this was over before we had heard any of the circumstances.

Captain John Timblestone immediately raised a squad of forty or fifty men, and taking

their plain trail came upon them on their way out, -- a large force of between four, and

five hundred Indians. Our Captain was nothing daunted however and ordered our men to fire

a charge upon them. He was brave, cool and deliberate, and I have always believed would

have whipped out that Indian force, if a misunderstanding among the men had not forced

him to draw off, with the loss of one man. The Indians charged upon the rear of our force,

which was composed of Mexicans, who came near stampeding, and thus brought great confusion

into our ranks. Tumblestone then followed along at a distance receiving recruits constantly.

By this time, the news being well ventilated here around Bastrop General Burleson raised

all the men possible and started out anxious to intercept them at "Plum Creek". Every now

and then we met runners, who were sent to bid Burleson come on. We rode till midnight,

then halted to rest our horses and very nearly next morning we were again on the warpath,

still meeting runners at regular intervals beseeching us to come on.

We fell in with the Guadelupe men in the edge of Big Prairie, near Plum Creek, about two

miles from where Lockhart now stands. We were now ordered to dismount, "lay aside every

weight" examine our arms and make ready for battle. Houston's men had gotten in ahead

of the Indians, and were lying in a little mot of timber, when they heard the Indians

coming on, seemingly ignorant of our close proximity to them, for they were singing,

whistling, yelling and indeed making every conceivable noise. Here while awaiting the

Indians, we of Burleson's force joined them. A double filed line of march was formed,

Burleson's forces from the Colorado, marching about one hundred yards to the right of

Houston's men from the Guadelupe, and in sight of the Indians. Four men were sent ahead

as videttes or spies and the rear guard of the Indians, consisting of four warriors,

turned and road leisurely back to meet them. Slowly and deliberately they came on making

no sign or move for fight. When within twenty steps of our spies, Col. Schwitzer raised

his gun and killed one, where upon the others beat a hasty retreat for their main force.

Burleson ordered us to "Spur up", and we rode very fast. We saw confusion in the Indian

ranks, which we could not then understand. A squad of men seemed retreating in face of

a pursuing band of Indians. They were evidently "divided against themselves or pursuing

some other body of men. At length we were discovered by the main force of Indians, who

immediately formed line between us, and their pack mules, stolen horses, where they awaited

us. When in one hundred and fifty yards of this line, we were ordered to dismount and one

man of the double file line held both horses, while his comrade shot. It was a strange

spectacle never to be forgotten, the wild, fantastic band, as they stood in battle array,

or swept around us with all strategy of Indian warfare. Twenty or thirty warriors mounted

upon splendid horses, tried to ride around us, sixty or eighty yards distant, firing upon

us as they went. It was a superstition among them, that if they could thus run around a

force, they could certainly vanquish it. Both horses and riders were decorated most

profusely, with all of the beauty and horror of their wild taste combined. Red ribbons

streamed out from the horses tails as they swept around us, riding fast, and carrying

all manner of stolen goods upon their heads and bodies. Here was a hugh warrior naked,

and wearing a stove pipe hat, another wore a fine pigeon tailed cloth coat, buttoned up

behind. They seemed to have a talent for finding and blending the strangest, most unheard

of ornaments. Some wore upon their heads immense buck, and buffalo horns, and one head

dress struck me particularly. It consisted of a large white crane with red eyes. In this

run-round, two warriors were killed, and a fine horse. We were now ordered to reload,

mount and charge. They at once retreated though a few stood until we were in fifteen

steps of them before starting. In the mean time the same warriors played around us at

the right, trying to divide our attention and force, while the main body of Indians

retreated firing as they went. Soon however they struck a very boggy bayou, into which

all of their pack mules and horses bogged down. A number of our men halted to take charge

of these and such a haul as they were making. The mules were literally loaded with all

manner of goods, some carrying even hoop irons to make arrow spikes. They bogged down

close together that a man could have walked along on their bodies dry. Still the Indians

retreated while the whites advanced, though the ranks on both sides were constantly

growing thinner, for at every thicket, a savage left his horse and took to bush, while

every now and then a horse fell under one of our men. Still about twenty warriors kept

up their play upon our right, while an equal number of our men kept them at bay. In this

side play Hurch Reid was wounded. He undertook to run on an Indian and shoot him. As

he passed, his gun snapped and before he could check his house, an arrow struck him, just

under the shoulder blade, piercing his lungs and lodging against his breast bone. Then

one of the most daring and best mounted of the warriors was killed by Jacob Burleson, who

was riding the notorious Duty roan, the race horse which a while back bore Mathew Duty to

his death and which finally fell into Indian hands. This broke up the side play. Burleson

with about twenty-five men pursued them to within a mile of the San Marcos River, where

they played out, and we retraced our steps.

One instance of the hardness and cruelty of some men, even though not savage in form and

color, was shown us on this raid. As was often the case some squaws were marching in Indian

ranks, and one of them had been shot, and lay breathing her last-almost dead, as we came by.

French Smith was most inhuman and unmanly cruelty, sprang upon her, stamped her and then

cut her body through with a lance. He was from Guadalupe, indeed I do not believe there

was a single man from Bastrop, who would have stooped to so brutal a deed. Ah men almost

forgot the meaning of love & mercy & forbearance amid the scenes through which we passed.

While halting to rest our horses, we heard a child cry, and a Mr. Carter upon going into

the thicket found a fine Indian baby, which had been left in the retreat. Joe Hornsby and

myself were riding about two hundred yards ahead of Burleson's main army, watching for

Indian trail and signs as we went. Suddenly we came in sight of about thirty Indians

some distance ahead. At first Joe said they were Tonkawas, who were a friendly tribe

living in our midst. Upon seeing their shields, however we knew they were hostile. I

galloped back to notify Burleson, while he kept his eye upon them. In thirty steps,

Burleson ordered us to fire and the action was simultaneous, though no one was hurt

only two horses killed. At one time here, I felt as if "my time" had come, sure enough.

We had fired one round, and I was down loading my gun when I saw an Indian approaching

me with gun presented. At this critical moment Joe Burleson shot, killing him instantly.

We discovered afterward that the Indian's gun was not loaded, and he was playing a

"bluff" game to get possession of my horse. We had a hot race after another warrior

on foot, who was unarmed except bow and arrow, but would turn and shot as he ran.

Gen. Burleson rushed at him with pistol presented, when an arrow from the Indian would

have killed him if he had not stepped back. Then the warrior aimed another arrow at

Monroe Hardeman, which missed him, but was driven eight inches into his horse. The

hardy warrior made a brave, and persistent fight, and even after he was knocked down,

drew his last arrow at me, the man nearest to him. I killed him just in time to save

myself. What fancies they had in the way of ornamenting themselves! This savage presented

a strange picture as he lay decked in beads etc, sleeping the "dreamless sleep" of death.

He also carried around his neck a tiny whistle and tin trumpet. The stolen horses, mules

and goods were divided among the soldiers, with the consent of the merchants, who could

not satisfactorily identify the articles. Among other things a Comanche mule fell to my

lot, and an odd specimen he was, with red ribbons on ears and tail. On return march, we

found a Texan dead and scalped. The explanation of his death furnished an explanation of

the confusion that was observed in the Indian ranks, on the advance. It happened in this

way. A squad of men on the Indian trail, came on their advanced guard and thinking they

could easily manage so small a force dismounted in a Live Oak Grove and awaited them.

Seeing the full force, however they mounted and retreated. One man, the unfortunate one

whom we found scalped was left by his horse as well as his comrades and thus had met his

terrible fate. We also found the body of Mrs. Crosby, whom they had killed when obliged

to retreat and near by we found Mrs. Watts, whom they had left for dead, having shot an

arrow full into her breast. A thick corset-board however received and impeded its force,

so that though wounded she was still alive. She was a remarkably fine looking woman,

but was sunburned almost to a blister. Gen. Burleson was riding his well known and much

admired horse, "Scurry" on this march, a present from Richard Scurry, an intimate friend

and valiant soldier, hence the horse's name. In 1841 the

Indians made a little raid into the Burleson neighborhood and stole a number of horses.

A small squad of men was raised quickly as possible, and pursuit was made. A run of

fifteen miles brought them in sight of the thieves at Ridgeway Fort on the waters of

the Yegua. The warriors were eating breakfast, and as our men, approached made no move

to retreat. The first fire killing two, and wounding one, they retreated. The whites

escaped unhurt, though one horse was shot. One their way from this skirmish, they went

to "Brushy Creek" and coming to Kinney's Fort, pretended to be friendly, but killed Dr.

Kinney and Castlebury. No pursuit being made, very soon they came again into the same

neighborhood, on the same errand and again they were successful. Among the other horses

stolen, was Burleson's celebrated, "Scurry". Gen. Burleson accompanied by eight or ten

men took their trail immediately and having followed them to the middle Yegua, came upon

them camped in the edge of a strip of timber about three quarters of a mile distant. They

had open prairie to run through, and all struck forward. Mr. Spaulding was riding a

splendid horse, the fastest runner of the crowd and he let out at full speed. The chase

was exciting to all, but Burleson was almost wild in his eagerness to regain "Scurry."

Seeing Spaulding making best speed he called out - "Twenty five dollars for Scurry,

Spaulding." Further on in a louder tone, he called - "Fifty dollars for Scurry, Spaulding!"

and still further on - "One hundred dollars for Scurry!" Much to his joy "Scurry" was

regained. Now Indian stealing became almost a constant thing. Sometimes they would make

a raid in the Stantiford neighborhood, then on Wilbarger Creek, and then in our immediate

vicinity, and along the Colorado, Indeed their boldness and greed became not only remarkable,

but alarming. A man was lying asleep in his wages and they took his horse which he tied to

one of the wheels, without waking him. Then they would come in day time and once were in

the act of trying to steal a little boy, when discovered. A small company of men at length

went out in pursuit. In Big Prairie on "Willbarger Creek", they saw a gang of "Mustangs"

feeding, while a solitary horse stood tied three or four hundred yards off. Their curiosity

was excited; but they soon saw Indians crawling upon the Mustangs-They were so engrossed

in trying to get the horses, that they did not discover the whites until they rushed upon

them. A running fight then commenced, the Indians retreating on foot, while we were riding.

Only one white man Mike Young was wounded, but not fatally, while three of the Indians

were killed and one old warrior crippled. It was touching to see the devotion of a

young Indian, presumably a son, who lingered by him a long time making every possible

effort t reach Brushy Bottom with him. As the whites gained ground and he saw death

would be the result of longer delay, he at length started off, but a few words from

the old Warrior recalled him. He tarried only long enough however to divide arrows

and then left his father to his fate. The time lost in helping the old man cost him

his life however, for he was overtaken and killed before reaching the bottom. Three

quarters of a mile further on, we discovered their camps, and from every sign, they

had brought their families and temporarily lived, for there was the print of children's

moccasins as well as those of squaws. But they had fled in alarm, and all was deserted.

The raids and persecutions of the Indians upon our vicinity became so frequent and

constant along now that it would be entirely superfluous to try to give in detail,

as well as impossible to chronicle them in regular order. After this raid occurred

the killing of another of our best citizens, Mr. William Lentz, who was way laid, and

shot near where Mr. Fallnash had been murdered sometime before. A little old cannon

used as a signal for our men to collect at Bastrop was a relic of the Mexican War,

having been dismounted and thrown into the San Antonio river by Philisoli at the battle

of San Jacinto. Immediately upon the murder of Mr. Lentz, the cannon called together

Burleson's little band which was promptly in pursuit, though as usual nothing was

accomplished. Mr. Hancock, one of our neighbors brought on eight or ten fine horses

from Tennessee, and in two weeks all of the, together with mine, and others were stolen.

A small squad of men under Captain Gillespie was soon in pursuit and with every advantage

this time, and we came in sight of them on Onion Creek, at what is known as "Marshack

Springs." When about a half mile off we charged upon them, where upon they mounted.

One of the warriors leading a very fine horse pretended to be leading a charge. Two

came round toward us, evidently trying to draw us off. The leading Indian was cut off,

and was chased about a mile up the creek by Campbell Taylor, and Jas Patten. They hemmed

him and Patten discharged both barrels of his gun without effect. The horse fell, and

the Indian though left afoot made his escape. In the mean time Captain Gillespie with

his body of men, hemmed the thieves so they were obligated to dismount, and leave their

horses all of which, were regained, except three.

In the spring of 1842 William Perry, William Barton, Henry Lentz and myself made arrangement

for a camp hunt. We took provisions intending to stay two or three nights. We made our way

toward the head of Lentz Branch intending to camp right at the Indian passway - although

the Indians were still very troublesome. We were riding leisurely along in couples about

eight miles from home and near our destination. Mr. Perry was entertaining us with accounts

of his numerous adventures among Indians on the Brazos and we were all much interested. No

matter now absorbed or entertained I might be however, I was always on the alert and wide

awake in the woods, though would go whatever dangers awaited me. In the midst of Perry's