Major Worth got tired of the monotony of a bachelor's life at Camp Apache and decided to give a dance in his quarters, and invite the chiefs. I think the other officers did not wholly approve of it, although they felt friendly enough towards them, as long as they were not causing disturbances. But to meet the savage Apache on a basis of social equality, in an officer's quarters, and to dance in a quadrille with him! Well, the limit of all things had been reached!

However, Major Worth, who was actually suffering from the ennui of frontier life in winter, and in time of peace, determined to carry out his project, so he had his quarters, which were quite spacious, cleared and decorated with evergreen boughs. From his company, he secured some men who could play the banjo and guitar, and all the officers and their wives, and the chiefs with their harems, came to this novel fête. A quadrille was formed, in which the chiefs danced opposite the officers. The squaws sat around, as they were too shy to dance. These chiefs were painted, and wore only their necklaces and the customary loincloth, throwing their blankets about their shoulderswhen they had finished dancing. I noticed again Chief Diablo's great good  l

l

l

llooks. is this man above diablo?

Conversation was carried on principally by signs and nods, and through the interpreter (a white man named Cooley). Besides, the officers had picked up many short phrases of the harsh and guttural Apache tongue.

Diablo was charmed with the young, handsome wife of one of the officers, and asked her husband how many ponies he would take for her, and Pedro asked Major Worth, if all those white squaws belonged to him.

The party passed off pleasantly enough, and was not especially subversive to discipline, although I believe it was not repeated.

Afterwards, long afterwards, when we were stationed at David's Island, New York Harbor, and Major Worth was no longer a bachelor, but a dignified married man and had gained his star in the Spanish War, we used to meet occasionally down by the barge office of taking a Fenster-promenade on Broadway, and we would always stand awhile and chat over the old days at Camp Apache in '74.

Never mind how pressing our mutual engagements were, we could never forego the pleasure of talking over those wild days and contrasting them with our then present surroundings. ‘‘“Shall you ever forget my party?”’’ he said, the last time we met.

Diablo, a chief of the Cibecue Apache, wass killed during a battle with a competing band of Indians.

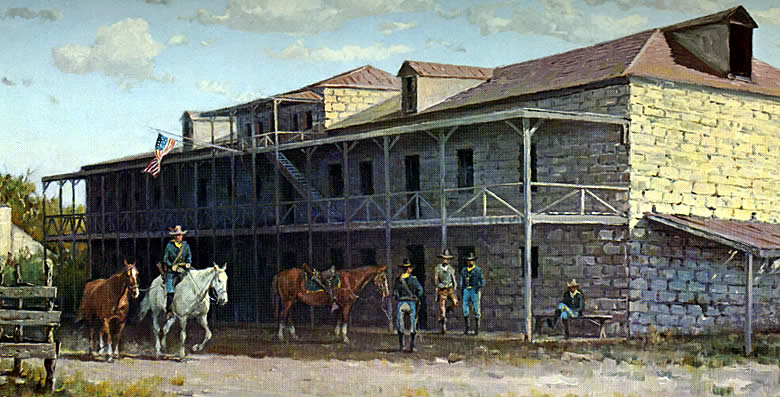

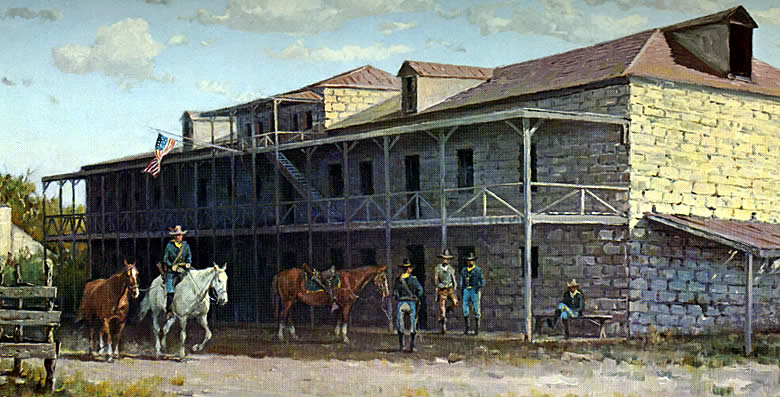

Known as Eskinlaw to his own people, Diablo was a prominent chief of the Cibecue Apache, who lived in the White Mountains of Arizona. Initially, Diablo had attempted to cooperate with the increasing number of whites who were encroaching on the Apache homeland. In July 1869, he traveled to Fort Defiance, the first American military post in Arizona, in hopes of establishing good relations. Three white men returned with Diablo and regular visits between the two groups began.below fort clark

Tensions, however, continued amongst the Apache themselves, many of whom were less welcoming to the Americans. In 1873, a warrior from a competing band of Apaches led by Eshkeldahsilah killed a white man working at the army's Fort Apache. Diablo tracked down the offending warrior and killed him, winning the Americans' praise but Eshkeldahsilah's increased enmity.

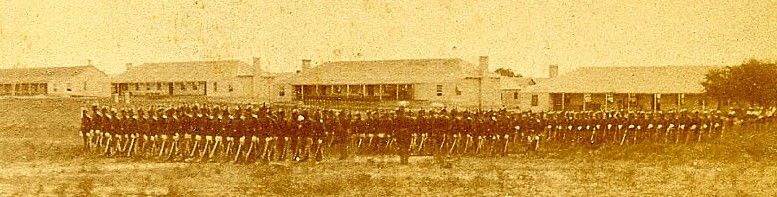

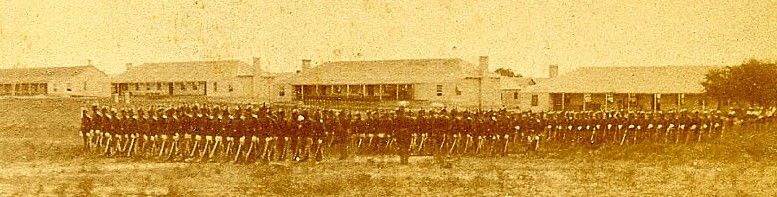

To avoid further violence, the commander of Fort Apache ordered all the surrounding tribes to move closer to the fort. This may have decreased the attacks on the Americans, but it increased the tensions between the Apache bands. The government further angered Diablo in July 1875, when it ordered that all of the Apaches in the region move to the San Carlos Reservation east of present-day Phoenix.below Seminole/Negro Indian scouts

In apparent frustration at the imperious behavior of the Americans, Diablo finally turned against the whites. In January 1876, he attacked the camp near Fort Apache, and he killed at least one white civilian. He also began attacking a competing band of White Mountain Apache who continued to cooperate with the Americans. Eventually, the White Mountain Apache got their revenge on Diablo. On this day in 1880, the two bands of Apache fought a fierce battle near Fort Apache. By the time the American military arrived on the site, Diablo's opponents had killed him.

N JANUARY our little boy arrived, to share our fate and to gladden our hearts. As he was the first child born to an officer's family in Camp Apache, there was the greatest excitement. All the sheep-ranchers and cattlemen for miles around came into the post. The beneficent canteen, with its soldiers' and officers' club-rooms, did not exist then. So they all gathered at the sutler's store, to celebrate events with a round of drinks. They wanted to shake hands with and congratulate the new father, after their fashion, upon the advent of the blond-haired baby. Their great hearts went out to him, and they vied with each other in doing the handsome thing by him, in a manner according to their lights, and their ideas of wishing well to a man; a manner, sometimes, alas! disastrous in its results to the man! However, by this time, I was getting used to all sides of frontier life.

I had no time to be lonely now, for I had no nurse, and the only person who was able to render me service was a laundress of the cavalry, who came for about two hours each day, until I was able to be up and take care of the child myself. Mounted men scoured the country around, to find me a nurse, but there was not a woman of girl to be heard of. Finally, thesutler sent word that a girl had been found in a Mexican wood-chopper's camp near by. She was sent up. I borrowed a Spanish dictionary from the sutler, and tried to teach the girl to be of some use to me, but she was very stupid, and I was glad when her wood-chopper husband came to fetch her home to his camp.

But to go back a little. The seventh day after the birth of the baby, a delegation of several squaws, wives of chiefs, came to pay me a formal visit. They brought me some finely woven baskets, and a beautiful pappoose-basket or cradle, such as they carry their own babies in. This was made of the lightest wood, and covered with the finest skin of fawn, tanned with birch bark by their own hands, and embroidered in blue beads; it was their best work. I admired it, and tried to express to them my thanks. These squaws took my baby (he was lying beside me on the bed), then, cooing and chuckling, they looked about the room, until they found a small pillow, which they laid into the basket-cradle, then put my baby in, drew the flaps together, and laced him into it; then stood it up, and laid it down, and laughed again in their gentle manner, and finally soothed him to sleep. I was quite touched by the friendliness of it all. They laid the cradle on the table and departed. Jack went out to bring Major Worth in, to see the pretty sight, and as the two entered the room, Jack pointed to the pappoose-basket.

Major Worth tip-toed forward, and gazed into the cradle; he did not speak for some time; then, in his inimitable way, and hall under his breath, he said, slowly, ‘‘“Well, I'll be d—d!”’’ This was all, but when he turned towards the bedside, and came and shook my hand, his eyes shone with a gentle and tender look.

And now there must be a bath-tub for the baby. The sutler rummaged his entire place, to find something that might do. At last, he sent me a freshly scoured tub, that looked as if it might, at no very remote date, have contained salt mackerel marked “A One.” So then, every morning at nine o'clock, our little half-window was black with the heads of the curious squaws and bucks, trying to get a glimpse of the fair baby's bath. A wonderful performance, it appeared to them.

Once a week this room, which was now a nursery combined with bedroom and living-room, was overhauled by the stalwart Bowen. The baby was put to sleep and laced securely into the pappoose-basket. He was then carried into the kitchen, laid on the dresser, and I sat by with a book or needle-work watching him, until Bowen had finished the room. On one of these occasions, I noticed a ledger lying upon one of the shelves. I looked into it, and imagine my astonishment, when I read: “Aunt Hepsey's. Below painting by Dale Gallon

Muffins,” “Sarah's Indian Pudding,” and on another page, “Hatty's Lemon Tarts,” “Aunt Susan's Method of Cooking a Leg of Mutton,” and “Josie Wells' Pressed Calf Liver.” Here were my own, my very own family recipes, copied into Bowen's ledger, in large illiterate characters; and on the fly-leaf, “Charles Bowen's Receipt Book.” I burst into a good hearty laugh, almost the first one I had enjoyed since I arrived at Camp Apache.

No comments:

Post a Comment