In Nantucket, no one thought much about the army.

The uniform of the regulars was never seen there. The profession of arms was scarcely known or heard of. Few people manifested any interest in the life of the Far West. I had, while there, felt out of touch with my oldest friends. Only my darling old uncle, a brave old whaling captain, had said: ‘‘“Mattie I am much interested in all you have written us about Arizona; come right down below and show me on the dining-room map just where you went.”’’

The uniform of the regulars was never seen there. The profession of arms was scarcely known or heard of. Few people manifested any interest in the life of the Far West. I had, while there, felt out of touch with my oldest friends. Only my darling old uncle, a brave old whaling captain, had said: ‘‘“Mattie I am much interested in all you have written us about Arizona; come right down below and show me on the dining-room map just where you went.”’’Gladly I followed him down the stairs, and he took his pencil out and began to trace. After he had crossed the Mississippi, there did not seem to be anything but blank country, and I could not find Arizona, and it was written in largo letters across the entire half of this antique map, “Unexplored.”

‘‘“True enough,”’’ he laughed. ‘‘“I must buy me a new map.”’’

But he drew his pencil around Cape Horn and up the Pacific coast, and I described to him the voyages I had made on the old “Newbern,” and his face was aglow with memories.

‘‘“Yes,”’’ he said, ‘‘“in 1826, we put into San Francisco harbor and sent our boats up to San JosÉ for

water and we took goats from some of those islands, too. Oh! I know the coast well enough. We were on our way to the Ar'tic Ocean then, after right whales.”’’

But, as a rule, people there seemed to have little interest in the army and it had made me feel as one apart.

Gila City was our first camp; not exactly a city, to be sure, at that time, whatever it may be now. We were greeted by the sight of a few old adobe houses, and the usual saloon. I had ceased, however, to dwell upon such trifles as names. Even “Filibuster,” the name of our next camp, elicited no remark from me.

The weather was fine beyond description. Each day, at noon, we got out of the ambulance, and sat down on the warm white sand, by a little clump of mesquite, and ate our luncheon. Coveys of quail flew up and we shot them, thereby insuring a good supper.

The mules trotted along contentedly on the smooth white road, which followed the south bank of the Gila River. Myriads of lizards ran out and looked at us. ‘‘“Hello, here you are again,”’’ they seemed to say.

The Gila Valley in December was quite a different thing from the Mojave desert in September; and although there was not much to see, in that low, flat country, yet we three were joyous and happy.

Good health again was mine, the travelling was

ideal, there were no discomforts, and I experienced no terrors in this part of Arizona.

Each morning, when the tent was struck, and I sat on the camp-stool by the little heap of ashes, which was all that remained of what had been so pleasant a home for an afternoon and a night, a little lonesome feeling crept over me, at the thought of leaving the place. So strong is the instinct and love of home in some people, that the little tendrils shoot out in a day and weave themselves around a spot which has given them shelter. Such as those are not born to be nomads.Below remains of Stanwix

Camps were made at Stanwix, Oatman flats (Below) and Gila Bend. There we left the river, which makes a mighty loop at this point, and struck across the plains to Maricopa Wells. The last day's march took us across the Gila River, over the Maricopa desert, and brought us to the Salt River.

We forded it at sundown, rested our animals a half hour or so, and drove through the MacDowell canon in the dark of the evening, nine miles more to the post. A day's march of forty-five miles. (A relay of mules had been sent to meet us at the Salt River, but by some oversight, we had missed it.)

We forded it at sundown, rested our animals a half hour or so, and drove through the MacDowell canon in the dark of the evening, nine miles more to the post. A day's march of forty-five miles. (A relay of mules had been sent to meet us at the Salt River, but by some oversight, we had missed it.)

Jack had told me of the curious cholla cactus, which is said to nod at the approach of human beings, and to deposit its barbed needles at their feet. Also I had heard stories of this deep, dark cañon and things that had happened there.below Oatman Flats

Fort MacDowell was in Maricopa County, Arizona, on the Verde River, seventy miles of so south of Camp Verde; the roving bands of Indiana, escaping from Camp Apache and the San Carlos reservation,

Grandson of Judge Henry Boyce and Irene Archinard, Powhatan was the son of Louise Frances Boyce and Powhatan Clarke. After finishing West Point, he served in the 10th U.S. Cavalry in Arizona. He was awarded the Congresional Medal of Honor for bravery in Battle, which he wears in this official portrait.

Grandson of Judge Henry Boyce and Irene Archinard, Powhatan was the son of Louise Frances Boyce and Powhatan Clarke. After finishing West Point, he served in the 10th U.S. Cavalry in Arizona. He was awarded the Congresional Medal of Honor for bravery in Battle, which he wears in this official portrait.Hence, a company of cavalry and one of infantry were stationed at Camp MacDowell, and the officers and men of this small command were kept busy, scouting, and driving the renegades from out of this part of the country back to their reservations. It was by no means an idle post, as I found after I got there; the life at Camp MacDowell meant hard work, exposure and fatigue for this small body of men.

As we wound our way through this deep, dark cañon, after crossing the Salt River below, I remembered the things I had heard, of ambush and murder. Our animals were too tired to go out of a walk, the night fell in black shadows down between those high mountain walls, the chollas, which are a pale sage-green color in the day-time, took on a ghastly hue. They were dotted here and there along the road, and on the steep mountain-sides. They grew nearly as tall as a man, and on each branch were great excrescences which looked like people's heads, in the vague light which fell upon them.

They nodded to us, and it made me shudder; they seemed to be something human.

The soldiers were not partial to MacDowell cañon; they knew too much about the place; and we all breathed a sigh of relief when we emerged from this dark uncanny road and saw the lights of the post, lying low, long, flat, around a square.WE WERE expected, evidently, for as we drove along the road in front of the officers' quarters they all came out to meet us, and we received a great welcome.

Captain Corliss of C company welcomed us to the post and to his company, and said he hoped I should like MacDowell better than I did Ehrenberg. Now Ehrenberg seemed years agone, and I could laugh at the mention of it.

Supper was awaiting us at Captain Corliss's, and Mrs. Kendall, wife of Lieutenant Kendall, Sixth Cavalry, had, in Jack's absence, put the finishing touches to our quarters. So I went at once to a comfortable home, and life in the army began again for me.

How good everything seemed! There was Doctor Clark, whom I had met first at Ehrenberg(above), and who wanted to throw Patrocina and Jesusíta into the Colorado. I was so glad to find him there; he was such a good doctor, and we never had a moment's anxiety, as long as he staid at Camp MacDowell. Our confidence in him was unbounded.

It was easy enough to obtain a man from the company. There were then no hateful laws forbidding soldiers to work in officers' families; no dreaded inspectors

who put the flat question, “Do you employ a soldier for menial labor?”

Captain Corliss gave me an old man by the name of Smith, and he was glad to come and stay with us and do what simple cooking we required. One of the laundresses let me have her daughter for nurserymaid, and our small establishment at Camp MacDowell moved on smoothly, if not with elegance.

The officers' quarters were a long, low line of adobe buildings with no space between them; the houses were separated only by thick walls. In front, the windows looked out over the parade ground. In the rear, they opened out on a road which ran along the whole length, and on the other side of which lay another row of long, low buildings which were the kitchens, each set of quarters having its own.

We occupied the quarters at the end of the row, and a large bay window looked out over a rather desolate plain, and across to the large and well-kept hospital. As all my draperies and pretty crÉtonnes had been burnt up on the ill-fated ship, I had nothing but bare white shades at the windows, and the rooms looked desolate enough. But a long divan was soon built, and some coarse yellow cotton bought at John Smith's (the sutler's) store, to cover it. My pretty rugs and mats were also gone, and there was only the old ingrain carpet from Fort Russell. The floors were adobe, and some men from the company came and laid down old canvas, then the carpet, and drove

[page 198]

in great spikes around the edge, to hold it down. The floors of the bedroom and dining-room were covered with canvas in the same manner. Our furnishings were very scanty and I felt very mournful about the loss of the boxes. We could not claim restitution, as the steamship company had been courteous enough to take the boxes down free of charge.

John Smith, the post trader (the name “sutler” fell into disuse about now), kept a large store, but nothing that I could use to beautify my quarters with,—and our losses had been so heavy that we really could not afford to send back East for more things. My new white dresses came, and were suitable enough for the winter climate of MacDowell. But I missed the thousand and one accessories of a woman's wardrobe, the accumulation of years, the comfortable things which money could not buy, especially at that distance.

I had never learned how to make dresses or to fit garments, and, although I knew how to sew, my accomplishments ran more in the line of outdoor sports.

But Mrs. Kendall, whose experience in frontier life had made her self-reliant, lent me some patterns, and I bought some of John Smith's calico and went to work to make gowns suited to the hot weather. This was in 1877, and every, one will remember that the ready-made house-gowns were not to be had in those days in the excellence and profusion in which they can to-day be found, in all parts of the country.

Now Mrs. Kendall was a tall, fine woman, much larger than I, but I used her patterns without alterations, and the result was something like a bag. They were freshly laundried and cool, however, and I did not place so much importance on the lines of them, as the young women of the present time do. To-day, the poorest farmer's wife in the wilds of Arkansas or Alaska can wear better fitting gowns than I wore then. But my riding habits, of which I had several kinds, to suit warm and cold countries, had been left in Jack's care at Ehrenberg, and as long as these fitted well, it did not so much matter about the gowns.(below Mexican infantry)

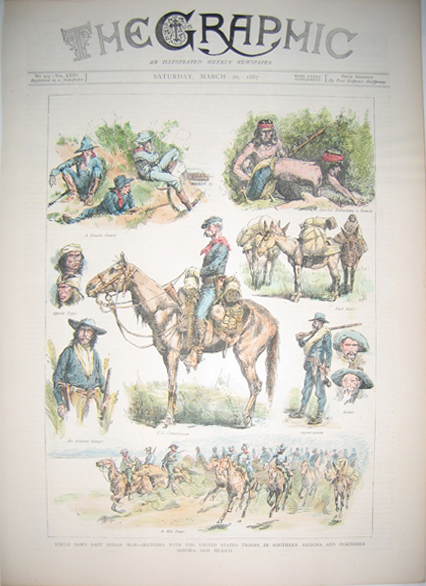

Captain Chaffee, who commanded the company of the Sixth Cavalry stationed there, was away on leave, but Mr. Kendall, his first lieutenaut, consented for me to exercise “Cochise,” Captain Chaffee's Indian pony, and I had a royal time.above mexicans and apache scouts below.I'm mnot sure of the period of the mexicans ,both riveresco. the mexicans are 28mm

Cavalry officers usually hate riding: that is, riding for pleasure; for they are in the saddle so much, for dead earnest work; but a young officer, a second lieutenant, not long out from the Academy, liked to ride, and we had many pleasant riding parties. Mr. Dravo and I rode one day to the Mormon settlement, seventeen miles away, on some business with the bishop, and a Mormon woman gave us a lunch of fried salt pork, potatoes, bread, and milk. How good it tasted, after our long ride! and how we laughed about it all, and jollied, after the fashion of young people, all the way back to the post! Mr. Dravo had also

[page 200]

lost all his things on the “Montana,” and we sympathized greatly with each other. He, however, had sent an order home to Pennsylvania, duplicating all the contents of his boxes. I told him I could not duplicate mine, if I sent a thousand orders East.

When, after some months, his boxes came, he brought me in a package, done up in tissue paper and tied with ribbon : ‘‘“Mother sends you these; she wrote that I was not to open them; I think she felt sorry for you, when I wrote her you had lost all your clothing. I suppose,”’’ he added, mustering his West Point French to the front, and handing me the package, ‘‘“it is what you ladies call ‘lingerie.’”’’

I hope I blushed, and I think I did, for I was not so very old, and I was touched by this sweet remembrance from the dear mother back in Pittsburgh. And so many lovely things happened all the time; everybody was so kind to me. Mrs. Kendall and her young sister, Kate Taylor, Mrs. John Smith and I, were the only women that winter at Camp MacDowell. Afterwards, Captain Corliss brought a bride to the post, and a new doctor took Doctor Clark's place.

There were interminable scouts, which took both cavalry and infantry out of the post. We heard a great deal about “chasing Injuns” in the Superstition Mountains, and once a lieutenant of infantry went out to chase an escaping Indian Agent.

Old Smith, my cook, was not very satisfactory; he drank a good deal, and I got very tired of the trouble

[page 201]

he caused me. It was before the days of the canteen, and soldiers could get all the whiskey they wanted at the trader's store; and, it being generally the brand that was known in the army as “Forty rod,” they got very drunk on it sometimes. I never had it in my heart to blame them much, poor fellows, for every human being wants and needs some sort of recreation and jovial excitement.

Captain Corliss said to Jack one day in my presence, ‘‘“I had a fine batch of recruits come in this morning.”’’

‘‘“That's lovely,”’’ said I; ‘‘“what kind of men are they? Any good cooks amongst them?”’’ (for I was getting very tired of Smith).

Captain Corliss smiled a grim smile. ‘‘“What do you think the United States Government enlists men for?”’’ said he; ‘‘“do you think I want my company to be made up of dish-washers?”’’

He was really quite angry with me, and I concluded that I had been too abrupt, in my eagerness for another man, and that my ideas on the subject were becoming warped. I decided that I must be more diplomatic in the future, in my dealings with the Captain of C company.

The next day, when we went to breakfast, whom did we find in the dining-room but Bowen! Our old Bowen of the long march across the Territory! Of Camp Apache and K company. He had his white

apron on, his hair rolled back in his most fetching style, and was putting the coffee on the table.

‘‘“But, Bowen,”’’ said I, ‘‘“where—how on earth—did you—how did you know we—what does it mean?”’’

Bowen saluted the First Lieutenant of C company, and said: ‘‘“Well, sir, the fact is, my time was out, and I thought I would quit. I went to San Francisco and worked in a miners' restaurant”’’ (here he hesitated), ‘‘“but I didn't like it, and I tried something else, and lost all my money, and I got tired of the town, so I thought I'd take on again, and as I knowed ye's were in C company now, I thought I'd come to MacDowell, and I came over here this morning and told old Smith he'd better quit; this was my job, and here I am, and I hope ye're all well—and the little boy?”’’

Here was loyalty indeed, and here was Bowen the Immortal, back again!

And now things ran smoothly once more. Roasts of beef and haunches of venison, ducks and other good things we had through the winter.

It was cool enough to wear white cotton dresses, but nothing heavier. It never rained, and the climate was superb, although it was always hot in the sun. We had heard that it was very hot here; in fact, people called MacDowell by very bad names. As the spring came on, we began to realize that the epithets applied to it might be quite appropriate.In front of our quarters was a ramáda, * supported by rude poles of the cottonwood tree. Then came the sidewalk, and the acÉquia (ditch), then a row of young cottonwood trees, then the parade ground. Through the acÉquia ran the clear water that supplied the post, and under the shade of the ramádas, hung the large ollas from which we dipped the drinking water, for as yet, of course, ice was not even dreamed of in the far plains of MacDowell. The heat became intense, as the summer approached. To sleep inside the house was impossible, and we soon followed the example of the cavalry, who had their beds out on the parade ground.

Two iron cots, therefore, were brought from the hospital, and placed side by side in front of our quarters, beyond the acÉquia and the cottonwood trees, in fact, out in the open space of the parade ground. Upon these were laid some mattresses and sheets, and after “taps” had sounded, and lights were out, we retired to rest. Near the cots stood Harry's crib. We had not thought about the ants, however, and they swarmed over our beds, driving us into the house. The next morning Bowen placed a tin can of water under each point of contact; and as each cot had eight legs, and the crib had four, twenty cans were necessary. He had not taken the trouble to remove the labels, and the pictures of red tomatoes glared at us

We had not thought about the ants, however, and they swarmed over our beds, driving us into the house. The next morning Bowen placed a tin can of water under each point of contact; and as each cot had eight legs, and the crib had four, twenty cans were necessary. He had not taken the trouble to remove the labels, and the pictures of red tomatoes glared at us

in the hot sun through the day; they did not look poetic, but our old enemies, the ants, were outwitted.

We did not look along the line, when we retired to our cots, but if we had, we should have seen shadowy figures, laden with pillows, flying from the houses to the cots or vice versa. It was certainly a novel experience.

With but a sheet for a covering, there we lay, looking up at the starry heavens. I watched the Great Bear go around, and other constellations and seemed to come into close touch with Nature and the mysterious night. But the melancholy solemnity of my communings was much affected by the howling of the coyotes, which seemed sometimes to be so near that I jumped to the side of the crib, to see if my little boy was being carried off. The good sweet slumber which I craved never came to me in those weird Arizona nights under the stars.

At about midnight, a sort of dewy coolness would come down from the sky, and we could then sleep a little; but the sun rose incredibly early in that southern country, and by the crack of dawn sheeted figures were to be seen darting back into the quarters, to try for another nap. The nap rarely came to any of us, for the heat of the houses never passed off, day of night, at that season. After an early breakfast, the long day began again.

The question of what to eat came to be a serious one. We experimented with all sorts of tinned foods, and

tried to produce some variety from them, but it was all rather tiresome. We almost dreaded the visits of the Paymaster and the Inspector at that season, as we never had anything in the house to give them.

One hot night, at about ten o'clock, we heard the rattle of wheels, and an ambulance drew up at our door. Out jumped Colonel Biddle, Inspector General, from Fort Whipple. ‘‘“What shall I give him to eat, poor hungry man?”’’ I thought. I looked in the wire-covered safe, which hung outside the kitchen, and discovered half a beefsteak-pie. The gallant Colonel declared that if there was one thing above all others that he liked, it was cold beefsteak-pie. Lieutenant Thomas of the Fifth Cavalry echoed his sentiments, and with a bottle of Cocomonga, which was always kept cooling somewhere, they had a merry supper.

These visits broke the monotony of our life at Camp MacDowell. We heard of the gay doings up at Fort Whipple, and of the lovely climate there.

Mr. Thomas said he could not understand why we wore such bags of dresses. I told him spitefully that if the women of Fort Whipple would come down to MacDowell to spend the summer, they would soon be able to explain it to him. I began to feel embarrassed at the fit of my house-gowns. After a few days spent with us, however, the mercury ranging from 104 to 120 degrees in the shade, he ceased to comment upon our dresses of our customs.

I had a glass jar of butter sent over from the Commissary, and asked Colonel Biddle if he thought it right that such butter as that should be bought by the purchasing officer in San Francisco. It had melted, and separated into layers of dead white, deep orange and pinkish-purple colors. Thus I, too, as well as General Miles, had my turn at trying to reform the Commissary Department of Uncle Sam's army.

Hammocks were swung under the ramádas, and after luncheon everybody tried a siesta. Then, near sundown, an ambulance came and took us over to the Verde River, about a mile away, where we bathed in water almost as thick as that of the Great Colorado. We taught Mrs. Kendall to swim, but Mr. Kendall, being an inland man, did not take to the water. Now the Verde River was not a very good substitute for the sea, and the thick water filled our ears and mouths, but it gave us a little half hour in the day when we could experience a feeling of being cool, and we found it worth while to take the trouble. Thick clumps of mesquite trees furnished us with dressing-rooms. We were all young, and youth requires so little with which to make merry.

After the meagre evening dinner, the Kendalls and ourselves sat together under the ramáda until taps, listening generally to the droll anecdotes told by Mr. Kendall, who had an inexhaustible fund. Then anotheright under the stars, and so passed the time away.

The Sunday inspection of men and barracks, which was performed with much precision and formality, and often in full dress uniform, gave us something by which we could mark the weeks, as they slipped along. There was no religious service of any kind, as Uncle Sam had not enough chaplains to go round. Those he had were kept for the larger posts, of those nearer civilization. The good Catholics read their prayer-books at home, and the non-religious people almost forgot that such organizations as churches existed.

Another bright winter found us still gazing at the Four Peaks of the MacDowell Mountains, the only landmark on the horizon. I was glad, in those days, that I had not staid back East, for the life of an officer without his family, in those drear places, is indeed a blank and empty one.

‘‘“Four years I have sat here and looked at the Four Peaks,”’’ said Captain Corliss, one day, ‘‘“and I'm getting almighty tired of it.”’’IN JUNE, 1878, Jack was ordered to report to the commanding officer at Fort Lowell (near the ancient city of Tucson), to act as Quartermaster and Commissary at that post. This was a sudden and totally unexpected order. It was indeed hard, and it seemed to me cruel. For our regiment had been four years in the Territory, and we were reasonably sure of being ordered out before long. Tucson lay far to the south of us, and was even hotter than this place. But there was nothing to be done; we packed up, I with a heavy heart, Jack with his customary stoicism.(below scott mingus)

With the grief which comes only at that time in one's life, and which sees no end and no limit, I parted from my friends at Camp MacDowell. Two years together, in the most intimate companionship, cut off from the outside world, and away from all early ties, had united us with indissoluble bonds,—and now we were to part,—forever as I thought.

We all wept; I embraced them all, and Jack lifted me into the ambulance; Mrs. Kendall gave a last kiss to our little boy; Donahue, our soldier-driver, loosened up his brakes, cracked his long whip, and away we went, down over the flat, through the dark MacDowell cañon, with the chollas nodding to us as we passed,

across the Salt River, and on across an open desert to Florence, forty miles or so to the southeast of us.

At Florence we sent our military transportation back and staid over a day at a tavern to rest. We met there a very agreeable and cultivated gentleman, Mr. Charles Poston, who was en route to his home, somewhere in the mountains near by. We took the Tucson stage at sundown, and travelled all night. I heard afterwards more about Mr. Poston: he had attained some reputation in the literary world by writing about the Sun-worshippers of Asia. He had been a great traveller in his early life, but now had built himself some sort of a house in one of the desolate mountains which rose out of these vast plains of Arizona, hoisted his sun-flag on the top, there to pass the rest of his days. People out there said he was a sun-worshipper. I do not know. ‘‘“But when I am tired of life and people,”’’ I thought, ‘‘“this will not be the place I shall choose.”’’

Arriving at Tucson(above), after a hot and tiresome night in the stage, we went to an old hostelry. Tucson looked attractive. Ancient civilization is always interesting to me.

Leaving me at the tavern, my husband drove out to Fort Lowell, to see about quarters and things in general. In a few hours he returned with the overwhelming news that he found a dispatch awaiting him at that post, ordering him to return immediately to his company at Camp MacDowell, as the Eighth Infantry

was ordered to the Department of California.

Ordered “out” at last! I felt like jumping up onto the table, climbing onto the roof, dancing and singing and shouting for joy! Tired as we were (and I thought I had reached the limit), we were not too tired to take the first stage back for Florence, which left that evening. Those two nights on the Tucson stage are a blank in my memory. I got through them somehow.

In the morning, as we approached the town of Florence, the great blue army wagon containing our household goods, hove in sight—its white canvas cover stretched over hoops, its six sturdy mules coming along at a good trot, and Sergeant Stone cracking his long whip, to keep up a proper pace in the eyes of the Tucson stage-driver.

Jack called him to halt, and down went the Sergeant's big brakes. Both teams came to a stand-still, and we told the Sergeant the news. Bewilderment, surprise, joy, followed each other on the old Sergeant's countenance. He turned his heavy team about, and promised to reach Camp MacDowell as soon as the animals could make it. At Florence, we left the stage, and went to the little tavern once more; the stage-route did not lie in our direction, so we must hire a private conveyance to bring us to Camp MacDowell. Jack found a man who had a good pair of ponies and an open buckboard. Towards night we set forth to

cross the plain which lies between Florence and the Salt River, due northwest by the map.

When I saw the driver I did not care much for his appearance. He did not inspire me with confidence, but the ponies looked strong, and we had forty or fifty miles before us.

After we got fairly into the desert, which was a trackless waste, I became possessed by a feeling that the man did not know the way. He talked a good deal about the North Star, and the fork in the road, and that we must be sure not to miss it.

It was a still, hot, starlit night. Jack and the driver sat on the front seat. They had taken the back seat out, and my little boy and I sat in the bottom of the wagon, with the hard cushions to lean against through the night. I suppose we were drowsy with sleep; at all events, the talk about the fork of the road and the North Star faded away into dreams.

Captain Corliss gave me an old man by the name of Smith, and he was glad to come and stay with us and do what simple cooking we required. One of the laundresses let me have her daughter for nurserymaid, and our small establishment at Camp MacDowell moved on smoothly, if not with elegance.

The officers' quarters were a long, low line of adobe buildings with no space between them; the houses were separated only by thick walls. In front, the windows looked out over the parade ground. In the rear, they opened out on a road which ran along the whole length, and on the other side of which lay another row of long, low buildings which were the kitchens, each set of quarters having its own.

We occupied the quarters at the end of the row, and a large bay window looked out over a rather desolate plain, and across to the large and well-kept hospital. As all my draperies and pretty crÉtonnes had been burnt up on the ill-fated ship, I had nothing but bare white shades at the windows, and the rooms looked desolate enough. But a long divan was soon built, and some coarse yellow cotton bought at John Smith's (the sutler's) store, to cover it. My pretty rugs and mats were also gone, and there was only the old ingrain carpet from Fort Russell. The floors were adobe, and some men from the company came and laid down old canvas, then the carpet, and drove

[page 198]

in great spikes around the edge, to hold it down. The floors of the bedroom and dining-room were covered with canvas in the same manner. Our furnishings were very scanty and I felt very mournful about the loss of the boxes. We could not claim restitution, as the steamship company had been courteous enough to take the boxes down free of charge.

John Smith, the post trader (the name “sutler” fell into disuse about now), kept a large store, but nothing that I could use to beautify my quarters with,—and our losses had been so heavy that we really could not afford to send back East for more things. My new white dresses came, and were suitable enough for the winter climate of MacDowell. But I missed the thousand and one accessories of a woman's wardrobe, the accumulation of years, the comfortable things which money could not buy, especially at that distance.

I had never learned how to make dresses or to fit garments, and, although I knew how to sew, my accomplishments ran more in the line of outdoor sports.

But Mrs. Kendall, whose experience in frontier life had made her self-reliant, lent me some patterns, and I bought some of John Smith's calico and went to work to make gowns suited to the hot weather. This was in 1877, and every, one will remember that the ready-made house-gowns were not to be had in those days in the excellence and profusion in which they can to-day be found, in all parts of the country.

Now Mrs. Kendall was a tall, fine woman, much larger than I, but I used her patterns without alterations, and the result was something like a bag. They were freshly laundried and cool, however, and I did not place so much importance on the lines of them, as the young women of the present time do. To-day, the poorest farmer's wife in the wilds of Arkansas or Alaska can wear better fitting gowns than I wore then. But my riding habits, of which I had several kinds, to suit warm and cold countries, had been left in Jack's care at Ehrenberg, and as long as these fitted well, it did not so much matter about the gowns.(below Mexican infantry)

Captain Chaffee, who commanded the company of the Sixth Cavalry stationed there, was away on leave, but Mr. Kendall, his first lieutenaut, consented for me to exercise “Cochise,” Captain Chaffee's Indian pony, and I had a royal time.above mexicans and apache scouts below.I'm mnot sure of the period of the mexicans ,both riveresco. the mexicans are 28mm

Cavalry officers usually hate riding: that is, riding for pleasure; for they are in the saddle so much, for dead earnest work; but a young officer, a second lieutenant, not long out from the Academy, liked to ride, and we had many pleasant riding parties. Mr. Dravo and I rode one day to the Mormon settlement, seventeen miles away, on some business with the bishop, and a Mormon woman gave us a lunch of fried salt pork, potatoes, bread, and milk. How good it tasted, after our long ride! and how we laughed about it all, and jollied, after the fashion of young people, all the way back to the post! Mr. Dravo had also

[page 200]

lost all his things on the “Montana,” and we sympathized greatly with each other. He, however, had sent an order home to Pennsylvania, duplicating all the contents of his boxes. I told him I could not duplicate mine, if I sent a thousand orders East.

When, after some months, his boxes came, he brought me in a package, done up in tissue paper and tied with ribbon : ‘‘“Mother sends you these; she wrote that I was not to open them; I think she felt sorry for you, when I wrote her you had lost all your clothing. I suppose,”’’ he added, mustering his West Point French to the front, and handing me the package, ‘‘“it is what you ladies call ‘lingerie.’”’’

I hope I blushed, and I think I did, for I was not so very old, and I was touched by this sweet remembrance from the dear mother back in Pittsburgh. And so many lovely things happened all the time; everybody was so kind to me. Mrs. Kendall and her young sister, Kate Taylor, Mrs. John Smith and I, were the only women that winter at Camp MacDowell. Afterwards, Captain Corliss brought a bride to the post, and a new doctor took Doctor Clark's place.

There were interminable scouts, which took both cavalry and infantry out of the post. We heard a great deal about “chasing Injuns” in the Superstition Mountains, and once a lieutenant of infantry went out to chase an escaping Indian Agent.

Old Smith, my cook, was not very satisfactory; he drank a good deal, and I got very tired of the trouble

[page 201]

he caused me. It was before the days of the canteen, and soldiers could get all the whiskey they wanted at the trader's store; and, it being generally the brand that was known in the army as “Forty rod,” they got very drunk on it sometimes. I never had it in my heart to blame them much, poor fellows, for every human being wants and needs some sort of recreation and jovial excitement.

Captain Corliss said to Jack one day in my presence, ‘‘“I had a fine batch of recruits come in this morning.”’’

‘‘“That's lovely,”’’ said I; ‘‘“what kind of men are they? Any good cooks amongst them?”’’ (for I was getting very tired of Smith).

Captain Corliss smiled a grim smile. ‘‘“What do you think the United States Government enlists men for?”’’ said he; ‘‘“do you think I want my company to be made up of dish-washers?”’’

He was really quite angry with me, and I concluded that I had been too abrupt, in my eagerness for another man, and that my ideas on the subject were becoming warped. I decided that I must be more diplomatic in the future, in my dealings with the Captain of C company.

The next day, when we went to breakfast, whom did we find in the dining-room but Bowen! Our old Bowen of the long march across the Territory! Of Camp Apache and K company. He had his white

apron on, his hair rolled back in his most fetching style, and was putting the coffee on the table.

‘‘“But, Bowen,”’’ said I, ‘‘“where—how on earth—did you—how did you know we—what does it mean?”’’

Bowen saluted the First Lieutenant of C company, and said: ‘‘“Well, sir, the fact is, my time was out, and I thought I would quit. I went to San Francisco and worked in a miners' restaurant”’’ (here he hesitated), ‘‘“but I didn't like it, and I tried something else, and lost all my money, and I got tired of the town, so I thought I'd take on again, and as I knowed ye's were in C company now, I thought I'd come to MacDowell, and I came over here this morning and told old Smith he'd better quit; this was my job, and here I am, and I hope ye're all well—and the little boy?”’’

Here was loyalty indeed, and here was Bowen the Immortal, back again!

And now things ran smoothly once more. Roasts of beef and haunches of venison, ducks and other good things we had through the winter.

It was cool enough to wear white cotton dresses, but nothing heavier. It never rained, and the climate was superb, although it was always hot in the sun. We had heard that it was very hot here; in fact, people called MacDowell by very bad names. As the spring came on, we began to realize that the epithets applied to it might be quite appropriate.In front of our quarters was a ramáda, * supported by rude poles of the cottonwood tree. Then came the sidewalk, and the acÉquia (ditch), then a row of young cottonwood trees, then the parade ground. Through the acÉquia ran the clear water that supplied the post, and under the shade of the ramádas, hung the large ollas from which we dipped the drinking water, for as yet, of course, ice was not even dreamed of in the far plains of MacDowell. The heat became intense, as the summer approached. To sleep inside the house was impossible, and we soon followed the example of the cavalry, who had their beds out on the parade ground.

Two iron cots, therefore, were brought from the hospital, and placed side by side in front of our quarters, beyond the acÉquia and the cottonwood trees, in fact, out in the open space of the parade ground. Upon these were laid some mattresses and sheets, and after “taps” had sounded, and lights were out, we retired to rest. Near the cots stood Harry's crib.

We had not thought about the ants, however, and they swarmed over our beds, driving us into the house. The next morning Bowen placed a tin can of water under each point of contact; and as each cot had eight legs, and the crib had four, twenty cans were necessary. He had not taken the trouble to remove the labels, and the pictures of red tomatoes glared at us

We had not thought about the ants, however, and they swarmed over our beds, driving us into the house. The next morning Bowen placed a tin can of water under each point of contact; and as each cot had eight legs, and the crib had four, twenty cans were necessary. He had not taken the trouble to remove the labels, and the pictures of red tomatoes glared at us

in the hot sun through the day; they did not look poetic, but our old enemies, the ants, were outwitted.

We did not look along the line, when we retired to our cots, but if we had, we should have seen shadowy figures, laden with pillows, flying from the houses to the cots or vice versa. It was certainly a novel experience.

With but a sheet for a covering, there we lay, looking up at the starry heavens. I watched the Great Bear go around, and other constellations and seemed to come into close touch with Nature and the mysterious night. But the melancholy solemnity of my communings was much affected by the howling of the coyotes, which seemed sometimes to be so near that I jumped to the side of the crib, to see if my little boy was being carried off. The good sweet slumber which I craved never came to me in those weird Arizona nights under the stars.

At about midnight, a sort of dewy coolness would come down from the sky, and we could then sleep a little; but the sun rose incredibly early in that southern country, and by the crack of dawn sheeted figures were to be seen darting back into the quarters, to try for another nap. The nap rarely came to any of us, for the heat of the houses never passed off, day of night, at that season. After an early breakfast, the long day began again.

The question of what to eat came to be a serious one. We experimented with all sorts of tinned foods, and

tried to produce some variety from them, but it was all rather tiresome. We almost dreaded the visits of the Paymaster and the Inspector at that season, as we never had anything in the house to give them.

One hot night, at about ten o'clock, we heard the rattle of wheels, and an ambulance drew up at our door. Out jumped Colonel Biddle, Inspector General, from Fort Whipple. ‘‘“What shall I give him to eat, poor hungry man?”’’ I thought. I looked in the wire-covered safe, which hung outside the kitchen, and discovered half a beefsteak-pie. The gallant Colonel declared that if there was one thing above all others that he liked, it was cold beefsteak-pie. Lieutenant Thomas of the Fifth Cavalry echoed his sentiments, and with a bottle of Cocomonga, which was always kept cooling somewhere, they had a merry supper.

These visits broke the monotony of our life at Camp MacDowell. We heard of the gay doings up at Fort Whipple, and of the lovely climate there.

Mr. Thomas said he could not understand why we wore such bags of dresses. I told him spitefully that if the women of Fort Whipple would come down to MacDowell to spend the summer, they would soon be able to explain it to him. I began to feel embarrassed at the fit of my house-gowns. After a few days spent with us, however, the mercury ranging from 104 to 120 degrees in the shade, he ceased to comment upon our dresses of our customs.

I had a glass jar of butter sent over from the Commissary, and asked Colonel Biddle if he thought it right that such butter as that should be bought by the purchasing officer in San Francisco. It had melted, and separated into layers of dead white, deep orange and pinkish-purple colors. Thus I, too, as well as General Miles, had my turn at trying to reform the Commissary Department of Uncle Sam's army.

Hammocks were swung under the ramádas, and after luncheon everybody tried a siesta. Then, near sundown, an ambulance came and took us over to the Verde River, about a mile away, where we bathed in water almost as thick as that of the Great Colorado. We taught Mrs. Kendall to swim, but Mr. Kendall, being an inland man, did not take to the water. Now the Verde River was not a very good substitute for the sea, and the thick water filled our ears and mouths, but it gave us a little half hour in the day when we could experience a feeling of being cool, and we found it worth while to take the trouble. Thick clumps of mesquite trees furnished us with dressing-rooms. We were all young, and youth requires so little with which to make merry.

After the meagre evening dinner, the Kendalls and ourselves sat together under the ramáda until taps, listening generally to the droll anecdotes told by Mr. Kendall, who had an inexhaustible fund. Then anotheright under the stars, and so passed the time away.

The Sunday inspection of men and barracks, which was performed with much precision and formality, and often in full dress uniform, gave us something by which we could mark the weeks, as they slipped along. There was no religious service of any kind, as Uncle Sam had not enough chaplains to go round. Those he had were kept for the larger posts, of those nearer civilization. The good Catholics read their prayer-books at home, and the non-religious people almost forgot that such organizations as churches existed.

Another bright winter found us still gazing at the Four Peaks of the MacDowell Mountains, the only landmark on the horizon. I was glad, in those days, that I had not staid back East, for the life of an officer without his family, in those drear places, is indeed a blank and empty one.

‘‘“Four years I have sat here and looked at the Four Peaks,”’’ said Captain Corliss, one day, ‘‘“and I'm getting almighty tired of it.”’’IN JUNE, 1878, Jack was ordered to report to the commanding officer at Fort Lowell (near the ancient city of Tucson), to act as Quartermaster and Commissary at that post. This was a sudden and totally unexpected order. It was indeed hard, and it seemed to me cruel. For our regiment had been four years in the Territory, and we were reasonably sure of being ordered out before long. Tucson lay far to the south of us, and was even hotter than this place. But there was nothing to be done; we packed up, I with a heavy heart, Jack with his customary stoicism.(below scott mingus)

With the grief which comes only at that time in one's life, and which sees no end and no limit, I parted from my friends at Camp MacDowell. Two years together, in the most intimate companionship, cut off from the outside world, and away from all early ties, had united us with indissoluble bonds,—and now we were to part,—forever as I thought.

We all wept; I embraced them all, and Jack lifted me into the ambulance; Mrs. Kendall gave a last kiss to our little boy; Donahue, our soldier-driver, loosened up his brakes, cracked his long whip, and away we went, down over the flat, through the dark MacDowell cañon, with the chollas nodding to us as we passed,

across the Salt River, and on across an open desert to Florence, forty miles or so to the southeast of us.

At Florence we sent our military transportation back and staid over a day at a tavern to rest. We met there a very agreeable and cultivated gentleman, Mr. Charles Poston, who was en route to his home, somewhere in the mountains near by. We took the Tucson stage at sundown, and travelled all night. I heard afterwards more about Mr. Poston: he had attained some reputation in the literary world by writing about the Sun-worshippers of Asia. He had been a great traveller in his early life, but now had built himself some sort of a house in one of the desolate mountains which rose out of these vast plains of Arizona, hoisted his sun-flag on the top, there to pass the rest of his days. People out there said he was a sun-worshipper. I do not know. ‘‘“But when I am tired of life and people,”’’ I thought, ‘‘“this will not be the place I shall choose.”’’

Arriving at Tucson(above), after a hot and tiresome night in the stage, we went to an old hostelry. Tucson looked attractive. Ancient civilization is always interesting to me.

Leaving me at the tavern, my husband drove out to Fort Lowell, to see about quarters and things in general. In a few hours he returned with the overwhelming news that he found a dispatch awaiting him at that post, ordering him to return immediately to his company at Camp MacDowell, as the Eighth Infantry

was ordered to the Department of California.

Ordered “out” at last! I felt like jumping up onto the table, climbing onto the roof, dancing and singing and shouting for joy! Tired as we were (and I thought I had reached the limit), we were not too tired to take the first stage back for Florence, which left that evening. Those two nights on the Tucson stage are a blank in my memory. I got through them somehow.

In the morning, as we approached the town of Florence, the great blue army wagon containing our household goods, hove in sight—its white canvas cover stretched over hoops, its six sturdy mules coming along at a good trot, and Sergeant Stone cracking his long whip, to keep up a proper pace in the eyes of the Tucson stage-driver.

Jack called him to halt, and down went the Sergeant's big brakes. Both teams came to a stand-still, and we told the Sergeant the news. Bewilderment, surprise, joy, followed each other on the old Sergeant's countenance. He turned his heavy team about, and promised to reach Camp MacDowell as soon as the animals could make it. At Florence, we left the stage, and went to the little tavern once more; the stage-route did not lie in our direction, so we must hire a private conveyance to bring us to Camp MacDowell. Jack found a man who had a good pair of ponies and an open buckboard. Towards night we set forth to

cross the plain which lies between Florence and the Salt River, due northwest by the map.

When I saw the driver I did not care much for his appearance. He did not inspire me with confidence, but the ponies looked strong, and we had forty or fifty miles before us.

After we got fairly into the desert, which was a trackless waste, I became possessed by a feeling that the man did not know the way. He talked a good deal about the North Star, and the fork in the road, and that we must be sure not to miss it.

It was a still, hot, starlit night. Jack and the driver sat on the front seat. They had taken the back seat out, and my little boy and I sat in the bottom of the wagon, with the hard cushions to lean against through the night. I suppose we were drowsy with sleep; at all events, the talk about the fork of the road and the North Star faded away into dreams.

No comments:

Post a Comment