I went to Fisher for everything—a large, well-built American, and a kind good man. Mrs. Fisher could not endure the life at Ehrenberg, so she lived in San Francisco, he told me.

There were several other white men in the place, and two large stores where everything was kept that people in such countries buy. These merchants made enormous profits, and their families lived in luxury in San Francisco.

There were several other white men in the place, and two large stores where everything was kept that people in such countries buy. These merchants made enormous profits, and their families lived in luxury in San Francisco.

The rest of the population consisted of a very poor class of Mexicans, Cocopah, Yuma and Mojave Indians, and half-breeds.

The duties of the army officer stationed here consisted principally in receiving and shipping the enormous quantity of Government freight which was landed by the river steamers.

It was shipped by wagon trains across the Territory, and at all times the work carried large responsibilities with it.

It was shipped by wagon trains across the Territory, and at all times the work carried large responsibilities with it.

I soon realized that however much the present incumbent might like the situation, it was no fit place for a woman.

The station at Ehrenberg was what we call, in the army, “detached service.” I realized that we had left the army for the time being; that we had cut loose from a garrison; that we were in a place where good food could not be procured, and where there were practically no servants to be had. That there was not a woman to speak to, or to go to for advice or help, and, worst of all, that there was no doctor in the place. Besides all this, my clothes were all ruined by lying wet for a fortnight in the boxes, and I had practically

nothing to wear. I did not then know what useless things clothes were in Ehrenberg.dragoon mountains

nothing to wear. I did not then know what useless things clothes were in Ehrenberg.dragoon mountainsThe situation appeared rather serious; the weather had grown intensely hot, and it was decided that the only thing for me to do was to go to San Francisco for the summer.

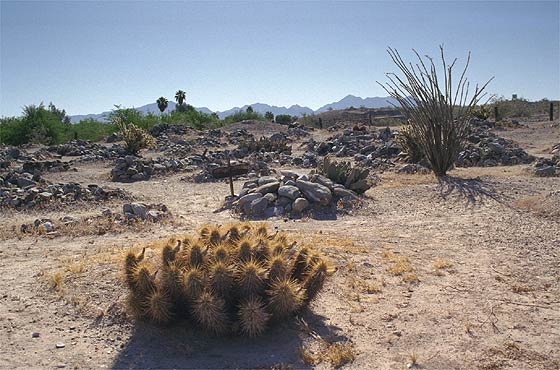

So one day we heard the whistle of the “Gila” going up; and when she came down river, I was all ready to go on board, with Patrocina and Jesusita, * and my own child, who was yet but five months old. I bade farewell to the man on detached service, and we headed down river. We seemed to go down very rapidly, although the trip lasted several days. Patrocina took to her bed with neuralgia (or nostalgia);her little devil of a child screamed the entire days and nights through, to the utter discomfiture of the few other passengers. A young lieutenant and his wife and an army surgeon were among the number, and they seemed to think that I could help it (though they did not say so).all thats left of Ehrenburg below

The cemetery is all that's left of old Ehrenberg. Ehrenberg was settled in 1867 and named for surveyor Herman Ehrenberg. By the mid-1870s the town had a population of about 500 and featured a hotel, a bakery and a stage station.

Finally the doctor said that if I did not throw Jesusta overboard, he would; why didn't I “wring the neck of its worthless Mexican of a mother?” and so on, until I really grew very nervous and unhappy, thinking what I should do after we got on board the ocean steamer. I, a victim of seasickness, with this unlucky woman and her child on my hands, in addition to my own! No; I made up my mind to go back to Ehrenberg, but I said nothing.

I did not dare to let Doctor Clark know of my decision, for I knew he would try to dissuade me; but when we reached the mouth of the river, and they began to transfer the passengers to the ocean steamer which lay in the offing, I quietly sat down upon my trunk and told them I was going back to Ehrenberg. Captain Mellon grinned; the others were speechless; they tried persuasion, but saw it was useless; and then they said good-bye to me, and our stern-wheeler headed about and started for up river.

Ehrenberg had become truly my old man of the sea; I could not get rid of it, There I must go, and there I must stay, until circumstances and the Fates were more propitious for my departure.THE WEEK we spent going up the Colorado in June was not as uncomfortable as the time spent on the river in August of the previous year. Everything is relative, I discovered, and I was happy in going back to stay with the First Lieutenant of C Company, and share his fortunes awhile longer.

Patrocina recovered, as soon as she found we were to return to Ehrenberg. I wondered how anybody could be so homesick for such a God-forsaken place. I asked her if she had ever seen a tree, or green grass (for I could talk with her quite easily now). She shook her mournful head. ‘‘“But don't you want to see trees and grass and flowers?”’’

Another sad shake of the head was the only reply.

Such people, such natures, and such lives, were incomprehensible to me then. I could not look at things except from my own standpoint.

She took her child upon her knee, and lighted a cigarette; I took mine upon my knee, and gazed at the river banks: they were now old friends: I had gazed at them many times before; how much I had experienced, and how much had happened since I first saw them! Could it be that I should ever come to love them, and the pungent smell of the arrow-weed which covered them to the water's edge? below barneys store Ehrenburg

The huge mosquitoes swarmed over us in the nights from those thick clumps of arrow-weed and willow, and the nets with which Captain Mellon provided us did not afford much protection.

The June heat was bad enough, though not quite so stifling as the August heat. I was becoming accustomed to climates, and had learned to endure discomfort. The salt beef and the Chinaman's peach pies were no longer offensive to me. Indeed, I had a good appetite for them, though they were not exactly the sort of food prescribed by the modern doctor, for a young mother. Of course, milk eggs, and all fresh food were not to be had on the river boats. Ice was still a thing unknown on the Colorado.

When, after a week, the “Gila” pushed her nose up to the bank at Ehrenberg, there stood the Quartermaster. He jumped aboard, and did not seem in the least surprised to see me. ‘‘“I knew you'd come back,”’’ said he. I laughed, of course, and we both laughed.

‘‘“I hadn't the courage to go on,”’’ I replied.

‘‘“Oh, well, we can make things comfortable here and get through the summer some way,”’’ he said. ‘‘“I'll build some rooms on, and a kitchen, and we can surely get along. It's the healthiest place in the world for children, they tell me.”’’

So after a hearty handshake with Captain Mellon, who had taken such good care of me on my week's voyage up river, I being almost the only passenger,

I put my foot once more on the shores of old Ehrenberg, and we wended our way towards the blank white walls of the Government house. I was glad to be back, and content to wait.

So work was begun immediately on the kitchen. My first stipulation was, that the new rooms were to have wooden floors; for, although the Cocopah Charley kept the adobe floors in perfect condition, by sprinkling them down and sweeping them out every morning, they were quite impossible, especially where it concerned white dresses and children, and the little sharp rocks in them seemed to be so tiring to the feet.

Life as we Americans live it was difficult in Ehrenberg. I often said: ‘‘“Oh! if we could only live as the Mexicans live, how easy it would be!”’’ For they had their fire built between some stones piled up in their yard, a piece of sheet iron laid over the top: this was the cooking-stove. A pot of coffee was made in the morning early, and the family sat on the low porch and drank it, and ate a biscuit. Then a kettle of frijoles * was put over to boil. These were boiled slowly for some hours, then lard and salt were added, and they simmered down until they were deliciously fit to eat, and had a thick red gravy.

Then the young matron, or daughter of the house, would mix the peculiar paste of flour and salt and water, for tortillas, a species of unleavened bread. These tortillas were patted out until they were as

]arge as a dinner plate, and very thin; then thrown onto the hot sheet-iron, where they baked. Each one of the family then got a tortilla, the spoonful of beans was laid upon it, and so they managed without the paraphernalia of silver and china and napery.

How I envied them the simplicity of their lives! Besides, the tortillas were delicious to eat, and as for the frijoles, they were beyond anything I had ever eaten in the shape of beans. I took lessons in the making of tortillas. A woman was paid to come and teach me; but I never mastered the art. It is in the blood of the Mexican, and a girl begins at a very early age to make the tortilla. It is the most graceful thing to see a pretty Mexican toss the wafer-like disc over her bare arm, and pat it out until transparent.

This was their supper; for, like nearly all people in the tropics, they ate only twice a day. Their fare was varied sometimes by a little carni seca, pounded up and stewed with chile verde or chile colorado.

Now if you could hear the soft, exquisite, affectionate drawl with which the Mexican woman says chile verde you could perhaps come to realize what an important part the delicious green pepper plays in the cookery of these countries.

They do not use it in its raw state, but generally roast it, stripping off the thin skin and throwing away the seeds, leaving only the pulp, which acquires a fine flavor by having been roasted or toasted over the hot coals.

The women were scrupulously clean and modest,and always wore, when in their casa, a low-necked and short-sleeved camisa, fitting neatly, with bands around neck and arms. Over this they wore a calico skirt; always white stockings and black slippers. When they ventured out, the younger women put on muslin gowns, and carried parasols. The older women wore a linen towel thrown over their heads, or, in cool weather, the black riboso. I often cried: ‘‘“Oh! if I could only dress as the Mexicans do! Their necks and arms do look so cool and clean.”’’

I have always been sorry I did not adopt their fashion of house apparel. Instead of that, I yielded to the prejudices of my conservative partner, and sweltered during the day in high-necked and long-sleeved white dresses, kept up the table in American fashion, ate American food in so far as we could get it, and all at the expense of strength; for our soldier cooks, who were loaned us by Captain Ernest from his company at Fort Yuma, were constantly being changed, and I was often left with the Indian and the indolent Patrocina. At those times, how I wished I had no silver, no table linen, no china, and could revert to the primitive customs of my neighbors!

There was no market, but occasionally a Mexican killed a steer, and we bought enough for one meal; but having no ice, and no place away from the terrific heat, the meat was hung out under the ramádawith a piece of netting over it, until the first heat had passed out of it, and then it was cooked.

The Mexican, after selling what meat he could, cut the rest into thin strips and hung it up on ropes to dry in the sun. It dried hard and brittle, in its natural state, so pure is the air on that wonderful river bank. They called this carni seca, and the Americans called it “jerked beef.”

Patrocina often prepared me a dish of this, when I was unable to taste the fresh meat. She would pound it fine with a heavy pestle, and then put it to simmer, seasoning it with the green or red pepper. It was most savory. There was no butter at all during the hot months, but our hens laid a few eggs, and the Quartermaster was allowed to keep a small lot of commissary stores, from which we drew our supplies of flour, ham, and canned things. We were often without milk for weeks at a time, for the cows crossed the river to graze, and sometimes could not get back until the river fell again.

Adversities suffered by the German settlers in Texas during the years 1846 and 1847 could have been reason enough to discourage them from immigrating to Texas unless they felt conditions in Germany were worse. Ludwig felt his life would be better in America.

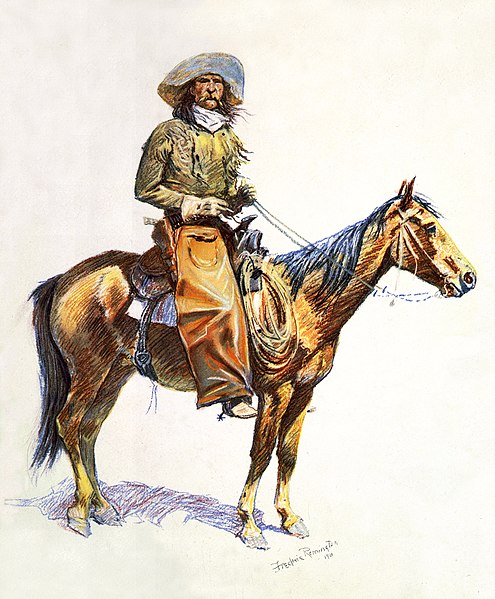

Many Germans left the German states to avoid hunger at home and many met nasty ends One called Ludwig set sail from the Rhine River to avoid fighting in a war. The irony was that he ended up serving with the Union Army during the Civil War where he was captured and forced to make confederate uniforms while in prison because he was a tailor by trade. When the Civil War ended, troops that had been withdrawn to fight in the war returned to Texas, including Ludwig, this time to stay until the frontier was tamed. In 1866, thousands of black cavalrymen were recruited by the United States government to open the west and fight the battles against the Indians.

These troops had brought peace to the plains and came to be known as the Buffalo Soldiers. (The nickname was given to them by the Indians of the plains who likened their hair to that of the buffalo.) In 1867 and 1868, federal troops re-occupied Forts Davis, Stockton, Lancaster and Quitman, this time building permanent housing and facilities of stone and adobe to replace the uncomfortable and unsanitary pre-war jacales (one-room Mexican adobe huts).

Ludwig Mueller (Louis Miller, the American translation), met and married Clara S. (Olmstead) Howard, a widow with five children in 1870. Her family lived at Fort Croghan, another fort in the Fisher-Miller grant which was about three miles south of the town of Burnet, TX. The Olmstead family had a contract with the government to supply food for another fort before the Civil War and may have been under contract now at Fort Croghan. Seven children were born to Ludwig and Clara while in Texas.

In 1880, Ludwig and his family were living at Fort Concho, TX. Two of Ludwig's step-sons, Herbert and Frank, ran a saloon at the fort. During the years of western expansion, army posts were established on the basis of anticipated use. Reacting to the fast changing needs of the country, the army would set up a post and then abandon it when no longer needed. This string of forts led westward as expansion proceeded. Victorio was a renegade Warm Springs Apache chief who had led a band of Indians for two years near Fort Concho, killing and terrorizing settlers. The need for Fort Concho ended as peace was established after the Victorio campaign ended in 1880 with his death.

This string of forts led westward as expansion proceeded. Victorio was a renegade Warm Springs Apache chief who had led a band of Indians for two years near Fort Concho, killing and terrorizing settlers. The need for Fort Concho ended as peace was established after the Victorio campaign ended in 1880 with his death.

Ludwig Mueller (Louis Miller, the American translation), met and married Clara S. (Olmstead) Howard, a widow with five children in 1870. Her family lived at Fort Croghan, another fort in the Fisher-Miller grant which was about three miles south of the town of Burnet, TX. The Olmstead family had a contract with the government to supply food for another fort before the Civil War and may have been under contract now at Fort Croghan. Seven children were born to Ludwig and Clara while in Texas.

In 1880, Ludwig and his family were living at Fort Concho, TX. Two of Ludwig's step-sons, Herbert and Frank, ran a saloon at the fort. During the years of western expansion, army posts were established on the basis of anticipated use. Reacting to the fast changing needs of the country, the army would set up a post and then abandon it when no longer needed.

This string of forts led westward as expansion proceeded. Victorio was a renegade Warm Springs Apache chief who had led a band of Indians for two years near Fort Concho, killing and terrorizing settlers. The need for Fort Concho ended as peace was established after the Victorio campaign ended in 1880 with his death.

This string of forts led westward as expansion proceeded. Victorio was a renegade Warm Springs Apache chief who had led a band of Indians for two years near Fort Concho, killing and terrorizing settlers. The need for Fort Concho ended as peace was established after the Victorio campaign ended in 1880 with his death.

Col. Benjamin H. Grierson of the 10th U.S. Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers left Fort Concho in 1882 and went to Fort Davis in west Texas before heading further west in 1884. Ludwig and his family followed him and the Buffalo Soldiers building forts from one western frontier post to another all the way into Arizona Territory. below concho

When the family was living at Fort Davis, Ludwig's step-daughter, Pearl Howard met and married John Fletcher Fairchild, a jailer who served for old Presidio County as well as being a deputy sheriff. He also was a bar keeper who built a two story saloon and house of ill repute which he sold in 1883 soon after building it.

Fletcher also worked as a deputy and saloon keeper in New Mexico and Arizona after leaving Texas. The family left Texas in the fall of 1884. Pearl and her husband had their first child on the way to Arizona along the San Antonio-El Paso Road (later Route 66) and decided to stay in the Fort Bayard, New Mexico area for a while. Ludwig, Clara and the children continued on with a wagon train toward Fort Huachuca in Arizona.

Fletcher also worked as a deputy and saloon keeper in New Mexico and Arizona after leaving Texas. The family left Texas in the fall of 1884. Pearl and her husband had their first child on the way to Arizona along the San Antonio-El Paso Road (later Route 66) and decided to stay in the Fort Bayard, New Mexico area for a while. Ludwig, Clara and the children continued on with a wagon train toward Fort Huachuca in Arizona.

Ludwig was unable to avoid war in his homeland of Germany and now was involved in Indian wars in this new land. When Texas was tamed, Ludwig had to move with the action into Indian territory in Arizona.

He made his living serving army posts so he had to go where the work was. He became a casualty of the Indian Wars on his way to Fort Huachuca,

He made his living serving army posts so he had to go where the work was. He became a casualty of the Indian Wars on his way to Fort Huachuca, being killed by marauding Apache Indians who attacked the wagon train traveling near Fort Apache (Safford), Arizona Territory. His wife and children were left behind because they couldn't keep up with the train and another group found them and took them to Phoenix. In 1892, they moved to Prescott where Ludwig and Clara's boys became a part of the new railroad industry in Arizona Territory. Ludwig never saw Prescott as his new home as did his family.

being killed by marauding Apache Indians who attacked the wagon train traveling near Fort Apache (Safford), Arizona Territory. His wife and children were left behind because they couldn't keep up with the train and another group found them and took them to Phoenix. In 1892, they moved to Prescott where Ludwig and Clara's boys became a part of the new railroad industry in Arizona Territory. Ludwig never saw Prescott as his new home as did his family.

No comments:

Post a Comment