The next morning we set out for Fort Whipple, making a long day's march, and arriving late in the evening.

‘‘“You have a sick child; give him to me;”’’ then I told her some things, and she said: ‘‘“I wonder he is alive.”’’ Then she took him under her charge and declared we should not leave her house until he was well again. She understood all about nursing, and day by day, under her good care, and Doctor Henry Lippincott's skilful treatment, I saw my baby brought back to life again. Can I ever forget Mrs. Aldrich's blessed kindness?FORT WHIPPLE officers house

Up to then, I had taken no interest in Camp MacDowell, where was stationed the company into which my husband was promoted.

The Fort Whipple gates, erected in 1864, were saved from being removed and stand in front of the Performance Hall at the Yavapai College. This was once the site of the entrance to the Fort.

The Fort Whipple gates, erected in 1864, were saved from being removed and stand in front of the Performance Hall at the Yavapai College. This was once the site of the entrance to the Fort. I knew it was somewhere in the southern part of the Territory, and isolated. The present was enough. I was meeting my old Fort Russell friends, and under Doctor Lippincott's good care I was getting back a measure of strength. Camp MacDowell was not yet a reality to me.

We met again Colonel Wilkins and Mrs. Wilkins and Carrie, and Mrs. Wilkins thanked me for bringing her daughter alive out of those wilds. Poor girl; 'twas but a few months when we heard of her death, at the birth of her second child. I have always thought her death was caused by the long hard journey from Apache to Whipple, for Nature never intended women to go through what we went through, on that memorable, journey by Stoneman's Lake.

There I met again Captain Porter, and I asked him if he had progressed any in his courtship, the railway came after the apache wars but not that long and he,

being very much embarrassed, said he did not know, but if patient waiting was of any avail, he believed he might win his bride.

After we had been at Whipple a few days, Jack came in and remarked casually to Lieutenant Aldrich, ‘‘“Well, I heard Bernard has asked to be relieved from Ehrenberg.”’’

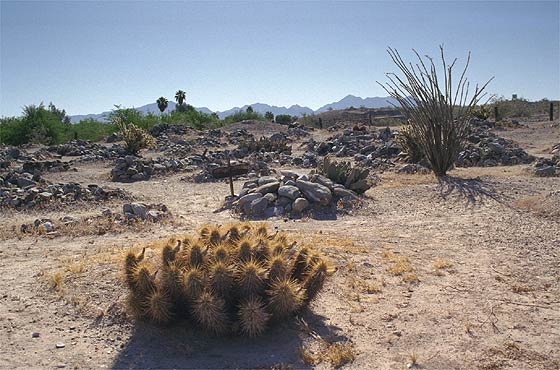

‘‘“What!”’’ I said, ‘‘“the lonely man down there on the river—the prisoner of Chillon—the silent one? Well, they are going to relieve him, of course?”’’Arizona spring

‘‘“Why, yes,”’’ said Jack, falteringly, ‘‘“if they can get anyone to take his place.”’’

‘‘“Can't they order some one?”’’ I inquired.

‘‘“Of course they can,”’’ he replied, and then, turning towards the window, he ventured: ‘‘“The fact is, Martha, I've been offered it, and am thinking it over.”’’ (The real truth was, that he had applied for it, thinking it possessed great advantages over Camp MacDowell.)

‘‘“What! do I hear aright? Have your senses left you? Are you crazy? Are you going to take me to that awful place? Why, Jack, I should die there!”’’

‘‘“Now, Martha, be reasonable; listen to me, and if you really decide against it, I'll throw up the detail. But don't you see, we shall be right on the river, the boat comes up every fortnight or so, you can jump aboard and go up to San Francisco.”’’ (Oh, how alluring that sounded to my ears!) ‘‘“Why, it's no trouble to get out of Arizona from Ehrenberg. Then,

too, I shall be independent, and can do just as I like, and when I like,”’’ et cætera, et cætera. ‘‘“Oh, you'll be making the greatest mistake, if you decide against it. As for MacDowell, it's a hell of a place, down there in the South; and you never will be able to go back East with the baby, if we once get settled down there. Why, it's a good fifteen days from the river.”’’

And so he piled up the arguments in favor of Ehrenberg, saying finally, ‘‘“You need not stop a day there. If the boat happens to be up, you can jump right aboard and start at once.”’’

All the discomforts of the voyage on the “Newbern,” and the memory of those long days spent on the river steamer in August had paled before my recent experiences. I flew, in imagination, to the deck of the “Gila,” and to good Captain Mellon, who would take me and my child out of that wretched Territory.

‘‘“Yes, yes, let us go then,”’’ I cried; for here came in my inexperience. I thought I was choosing the lesser evil, and I knew that Jack believed it to be so, and also that he had set his heart upon Ehrenberg, for reasons known only to the understanding of a military man.

So it was decided to take the Ehrenberg detail.AT THE end of a week, we started forth for Ehrenberg. Our escort was now sent back to Camp Apache, and the Baileys remained at Fort Whipple, so our outfit consisted of one ambulance and one army wagon. One or two soldiers went along, to help with the teams and the camp.

We travelled two days over a semi-civilized country, and found quite comfortable ranches where we spent the nights. The greatest luxury, was fresh milk, and we enjoyed that at these ranches in Skull Valley. They kept American cows, and supplied Whipple Barracks with milk and butter. We drank, and drank, and drank again, and carried a jugful to

our bedside. The third day brought us to Cullen's ranch, at the edge of the desert. Mrs. Cullen was a Mexican woman and had a little boy named Daniel; she cooked us a delicious supper of stewed chicken, and fried eggs, and good bread, and then she put our boy to bed in Daniel's crib. I felt so grateful to her; and with a return of physical comfort, I began to think that life, after all, might be worth the living. (below typical watering hole Tysons well)

our bedside. The third day brought us to Cullen's ranch, at the edge of the desert. Mrs. Cullen was a Mexican woman and had a little boy named Daniel; she cooked us a delicious supper of stewed chicken, and fried eggs, and good bread, and then she put our boy to bed in Daniel's crib. I felt so grateful to her; and with a return of physical comfort, I began to think that life, after all, might be worth the living. (below typical watering hole Tysons well)

Hopefully and cheerfully the next morning we entered the vast Colorado desert. This was verily the desert, more like the desert which our imagination pictures, than the one we had crossed in September from Mojave. It seemed so white, so bare, so endless, and so still; irreclaimable, eternal, like Death itself.

The stillness was appalling. We saw great numbers of lizards darting about like lightning; they were nearly as white as the sand itself, and sat up on their hind legs and looked at us with their pretty, beady black eyes. It seemed very far off from everywhere and everybody, this desert—but I knew there was a camp somewhere awaiting us, and our mules trotted patiently on. Towards noon they began to raise their heads and sniff the air; they knew that water was near.old watering hole below

They quickened their pace, and we soon drew up before a large wooden structure. There were no trees nor grass around it. A Mexican worked the machinery with the aid of a mule, and water was bought for our twelve animals, at so much per head. The place was called Mesquite Wells; the man dwelt Mesquite Wells

They quickened their pace, and we soon drew up before a large wooden structure. There were no trees nor grass around it. A Mexican worked the machinery with the aid of a mule, and water was bought for our twelve animals, at so much per head. The place was called Mesquite Wells; the man dwelt Mesquite Wellsalone in his desolation, with no living being except his mule for company. How could he endure it! I was not able, even faintly, to comprehend it; I had not lived long enough.

He occupied a small hut, and there he staid, year in and year out, selling water to the passing traveller; and I fancy that travellers were not so frequent at Mesquite Wells a quarter of a century ago.

The thought of that hermit and his dreary surroundings filled my mind for a long time after we drove away, and it was only when we halted and a soldier got down to kill a great rattlesnake near the ambulance, that my thoughts were diverted. The man brought the rattles to us and the new toy served to amuse my little son.

At night we arrived at Desert Station. There was a good ranch there, kept by Hunt and Dudley, Englishmen, I believe. I did not see them, but I wondered who they were and why they staid in such a place.

They were absent at the time; perhaps they had mines or something of the sort to look after. One is always imagining things about people who live in such extraordinary places. At all events, whatever Messrs. Hunt and Dudley were doing down there, their ranch was clean and attractive, which was more than could be said of the place where we stopped the next night, a place called Tyson's Wells.

We slept in our tent that night, for of all places on the earth a poorly kept ranch in Arizona is the most melancholy andUNDER THE burning mid-day sun of Arizona, on May 16th, our six good mules, with the long whip cracking about their ears, and the ambulance rattling merrily along, brought us into the village of Ehrenberg.

We slept in our tent that night, for of all places on the earth a poorly kept ranch in Arizona is the most melancholy andUNDER THE burning mid-day sun of Arizona, on May 16th, our six good mules, with the long whip cracking about their ears, and the ambulance rattling merrily along, brought us into the village of Ehrenberg.  The cemetery is all that's left of old Ehrenberg. Ehrenberg was settled in 1867 and named for surveyor Herman Ehrenberg. By the mid-1870s the town had a population of about 500 and featured a hotel, a bakery and a stage station

The cemetery is all that's left of old Ehrenberg. Ehrenberg was settled in 1867 and named for surveyor Herman Ehrenberg. By the mid-1870s the town had a population of about 500 and featured a hotel, a bakery and a stage stationThere was one street, so called, which ran along on the river bank, and then a few cross streets straggling back into the desert, with here and there a low adobe casa. The Government house stood not far from the river, and as we drove up to the entrance the same blank white walls stared at me. It did not look so much like a prison, after all, I thought. Captain Bernard, the man whom I had pitied, stood at the doorway, to greet us, and after we were inside the house he had some biscuits and wine brought; and then the change of stations was talked of, and he said to me, ‘‘“Now, please make yourself at home. The house is yours; my things are virtually packed up, and I leave in a day or two. There is a soldier here who can stay with you; he has been able to attend to my simple wants. I eat only twice a day; and there is Charley, my Indian, who fetches the water from the river and does the chores. I dine generally at sundown.”’’ colorado near the village

The house was a one-story adobe. It formed two sides of a hollow square; the other two sides were a (fort Tyson)

high wall, and the Government freight-house respectively. The courtyard was partly shaded by a ramáda and partly open to the hot sun. There was a chicken-yard in one corner of the inclosed square, and in the centre stood a rickety old pump, which indicated some sort of a well. Not a green leaf or tree or blade of grass in sight. Nothing but white sand, as far as one could see, in all directions.

Inside the house there were bare white walls, ceilings covered with manta, and sagging, as they always do; small windows set in deep embrasures, and adobe floors. Small and inconvenient rooms, opening one into another around two sides of the square. A sort of low veranda protected by lattice screens, made from a species of slim cactus, called ocotÉa, woven together, and bound with raw-hide, ran around a part of the house.

Our dinner was enlivened by some good Cocomonga wine. I tried to ascertain something about the source of provisions, but evidently the soldier had done the foraging, and Captain Bernard admitted that it was difficult, adding always that he did not require much, ‘‘“it was so warm,”’’ et cætera, et cætera. The next morning I took the reins, nominally, but told the soldier to go ahead and do just as he had always done.

I selected a small room for the baby's bath, the all important function of the day. The Indian, a fine-looking Cocopah, of about twenty-four, brought me a large tub (the same sort of a half of a vinegar

barrel we had used at Apache for ourselves), set it down in the middle of the floor, and brought water from a barrel which stood in the corral. A low box was placed for me to sit on. This was a bachelor establishment, and there was no place but the floor to lay things on; but what with the splashing and the leaking and the dripping the floor turned to mud, and all the white clothes and towels were covered with it, and I myself was a sight to behold. The Indian stood smiling at my plight. He spoke only a pigeon English, but said, ‘‘“Too much-ee wet.”’’

I was in despair; things began to look hopeless again to me. I thought ‘‘“surely these Mexicans must know how to manage with these floors.”’’ Fisher, the steamboat agent, came in, and I asked him if he could not find me a nurse. He said he would try, and went out to see what could be done.

He finally brought in a rather forlorn looking Mexican woman leading a little child (whose father was not known), and she said she would come to us for quinze pesos a month. I consulted with Fisher, and he said she was a pretty good sort, and that we could not afford to be too particular down in that country. And so she came; and although she was indolent, and forever smoking cigarettes, she did care for the baby, and fanned him when he slept, and proved a blessing to me.

And now came the unpacking of our boxes, which had floated down the Colorado Chiquito below. The fine damask, brought from Germany for my linen chest, was a mass of mildew; and when the books came to light, I could have wept to see the pretty editions of Schiller, Goethe, and Lessing, which I had bought in Hanover, fall out of their bindings; the latter, warped out of all shape, and some of them unrecognizable. I did the best I could, however, not to show too much concern, and gathered the pages carefully together, to dry them in the sun.

They were my pride, my best beloved possessions, the links that bound me to the happy days in old Hanover.

No comments:

Post a Comment