The Indian brought the water every morning in buckets from the river. It looked like melted chocolate. He filled the barrels, and when it had settled clear, the ollas were filled, and thus(below Valiant miniatures) the drinking water was a trifle cooler than the air. One day it seemed unusually cool, so I said:

mins ‘‘“Let us see by the thermometer how cool the water really is.”’’ We found the temperature of the water to be 86 degrees; but that, with the air at 122 in the shade, seemed quite refreshing to drink.

mins ‘‘“Let us see by the thermometer how cool the water really is.”’’ We found the temperature of the water to be 86 degrees; but that, with the air at 122 in the shade, seemed quite refreshing to drink.

Abe Frank (the mail contractor), and one or two of the younger merchants. If I wanted anything, I went to Fisher. He always could solve the difficulty.

He procured for me an excellent middle-aged laundress, who came and brought the linen herself, and, bowing to the floor, said always, ‘‘“Buenos dias, Senorita!”’’ dwelling on the latter word, as a gentle compliment to a younger woman, and then, ‘‘“Mucho calor este dia,”’’ in her low, drawling voice.

He procured for me an excellent middle-aged laundress, who came and brought the linen herself, and, bowing to the floor, said always, ‘‘“Buenos dias, Senorita!”’’ dwelling on the latter word, as a gentle compliment to a younger woman, and then, ‘‘“Mucho calor este dia,”’’ in her low, drawling voice.

Like the others, she was spotlessly clean, modest and gentle. I asked her what on earth they did about bathing, for I had found the tub baths with the muddy water so disagreeable. She told me the women bathed in the river at daybreak, and asked me if I (below valiant mins)would like to go with

them.

I was only too glad to avail myself of her invitation, and so, like Pharoah's daughter of old, I went with my gentle handmaiden every morning to the river bank, and, wading in about knee-deep in the thick red waters, we sat down and let the (below pegaso mins)swift current flow by us.

We dared not go deeper, as the currents were so tremendously strong that we could not keep our foothold. But the swiftly-moving muddy water was vastly to be preferred to the muddy tub.

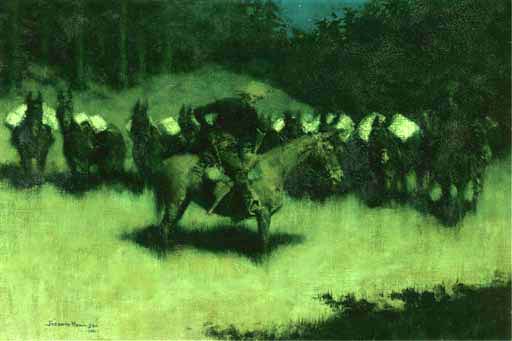

We dared not go deeper, as the currents were so tremendously strong that we could not keep our foothold. But the swiftly-moving muddy water was vastly to be preferred to the muddy tub.A clump of low mesquite trees at the top of the bank afforded sufficient protection at that hour; we rubbed dry, slipped on a loose gown, and wended our way home. What a contrast to the limpid, bracing salt waters of my own beloved shores!( by Remington)

When I thought of them, I was seized with a longing which consumed me and made my heart sick; and I thought of these poor people, who had never known anything in their lives but those desert places, and that muddy red water, and wondered what they would do, how they would act, if transported into some beautiful forest, or to the cool bright shores where clear blue waters invite to a plunge.(below both models modelbrau)

Whenever the river-boat came up, we were sure to have guests, for many officers went into the Territory via Ehrenberg. Sometimes the “transportation” was awaiting them; at other times, they were obliged to wait at Ehrenberg until it arrived. They usually lived on the boat; as we had no extra rooms, but I generally asked them to luncheon or supper (for anything that could be called a dinner was out of the question).

This caused me some anxiety, as there was nothing to be had; but I remembered the hospitality I had received, and thought of what they had been obliged to eat on the voyage, and I always asked them to share what we could provide, however simple it might be.

At such times we heard all the news from Washington and the States, and all about the fashions, and they, in their turn, asked me all sorts of questions about Ehrenberg and how I managed to endure the life. They were always astonished when the Cocopah Indian waited on them at table, for he wore nothing

but his loin-cloth, with about a yard of calico floating out behind, and although it was an every-day matter to us, it rather took their breath away

But “Charley” appealed to my æsthetic sense in every way. Tall, and well-made, with clean-cut limbs and features, fine smooth copper-colored skin, handsome face, heavy black hair done up in pompadour fashion and plastered with Colorado mud, which was baked white by the sun, a small feather at the crown of his head, wide turquoise bead bracelets upon his upper arm, and a knife at his waist—this was my Charley, my half-tame Cocopah, my man about the place, my butler in fact, for Charley understood how to open a bottle of Cocomonga gracefully, and to pour it as well.

Charley also wheeled the baby out along the river banks, for we had had a fine (above plastic conversion by eric stabler)“perambulator” sent down from San Francisco. It was an incongruous sight, to be sure, and one must laugh to think of it. The Ehrenberg babies did not have carriages, and the village flocked to see it. There sat the fair-haired, six-months-old boy, with but one linen garment on, no cap, no stockings—and this wild man of the desert, his knife gleaming at his waist, and his loin-cloth floating out behind, wheeling and pushing the carriage along the sandy roads.

But this came to an end; for one day Fisher rushed in, breathless, and said: ‘‘“Well! here is your baby! I was just in time, for that Injun of yours left the (below Histomin)

carriage in the middle of the street, to look in at the store window, and a herd of wild cattle came tearing down! I grabbed the carriage to the sidewalk, cussed the Injun out, and here's the child! It's no use,”’’ he added, ‘‘“you can't trust those Injuns out of sight.”’’

The heat was terrific. Our cots were placed in the open part of the corral (as our courtyard was always called). It was a desolate-looking place; on one side, the high adobe wall; on another, the freight-house; and on the other two, our apartments. Our kitchen and the two other rooms were now completed. The kitchen had no windows, only open spaces to admit the air and light, and we were often startled in the night by the noise of thieves in the house, rummaging for food.

At such times, our soldier-cook would rush into the corral with his rifle, the Lieutenant would jump up and seize his shotgun, which always stood near by, and together they would roam through the house. But the thieving Indians could jump out of the windows as easily as they jumped in, and the excitement would soon be over.

The violent sand-storms which prevail in those deserts, sometimes came up in the night, without warning; then we rushed half suffocated and blinded into the house, and as soon as we had closed the windows it had passed on, leaving a deep layer of sand on everything in the room, and on ourselves as well.below histomin

Then came the work, next day, for the Indian had to carry everything out of doors; and one storm was so bad that he had to use a shovel to remove the sand from the floors. The desert literally blew into the house.

And now we saw a singular phenomenon. In the late afternoon of each day, a hot steam would collect over the face of the river, then slowly rise, and floating over the length and breadth of this wretched hamlet of Ehrenberg, descend upon and envelop us. Thus we wilted and perspired, and had one part of the vapor bath without its bracing concomitant of the cool shower. In a half hour it was gone, but always left me prostrate; then Jack gave me milk punch, if milk was at hand, or sherry and egg, or something to bring me up to normal again. We got to dread the steam so; it was the climax of the long hot day and was peculiar to that part of the river.

The paraphernalia by the side of our cots at night consisted of a pitcher of cold tea, a lantern, matches, a revolver, and a shotgun. Enormous yellow cats, which lived in and around the freight-house, darted to and fro inside and outside the house, along the ceiling-beams, emitting loud cries, and that alone was enough to prevent sleep. In the old part of the house, some of the partitions did not run up to the roof, but were left open (for ventilation, I suppose), thus making a fine play-ground for cats and rats, which darted along, squeaking, meowing and clattering all the night.below Comanche histomin 54mm

through. An uncanny feeling of insecurity was ever with me. What with the accumulated effect of the day's heat, what with the thieving Indians, the sandstorms and the cats, our nights by no means gave us the refreshment needed by our worn-out systems. By the latter part of the summer, I was so exhausted by the heat and the various difficulties of living, that I had become a mere shadow of my former self.

Men and children seem to thrive in those climates, but it is death to women.

It was in the late summer that the boat arrived one day bringing a large number of staff officers and their wives, head clerks, and “general service” men for Fort Whipple. They had all been stationed in Washington for a number of years, having had what is known in the army as “gilt-edged” details. I went to the boat to call on them, and, remembering my voyage from San Francisco the year before, prepared to sympathize with them. But they had met their fate with resignation; knowing they should find a good climate and a pleasant post up in the mountains, and as they had no young children with them, they were disposed to make merry over their discomforts.

We asked them to come to our quarters for supper, and to come early, as any place was cooler than the boat, lying down there in the melting sun, and nothing to look upon but those hot zinc-covered decks or the ragged river banks, with their uninviting huts scattered along the edge.

The surroundings somehow did not fit these people. Now Mrs. Montgomery at Camp Apache seemed to have adapted herself to the rude setting of a log cabin in the mountains, but these were Staff people and they had enjoyed for years the civilized side of army life; now they were determined to rough it, but they did not know how to begin.

The beautiful wife of the Adjutant-General was mourning over some freckles which had come to adorn her dazzling complexion, and she had put on a large hat with a veil. Was there ever anything so incongruous as a hat and veil in Ehrenberg! For a long time I had not seen a woman in a hat; the Mexicans all wore a linen towel over their heads.

But her beauty was startling, and, after all, I thought, a woman so handsome must try to live up to her reputation.

Now for some weeks Jack had been investigating the sulphur well, which was beneath the old pump in our corral. He had had a long wooden bath-tub built, and I watched it with a lazy interest, and observed his glee as he found a longshoreman or roustabout who could caulk it. The shape was exactly like a coffin (but men have no imaginations), and when I told him how it made me feel to look at it, he said: ‘‘“Oh! you are always thinking of gloomy things. It's a fine tub, and we are mighty lucky to find that man to caulk it. I'm going to set it up in the little square room, and lead the sulphur water into it, and

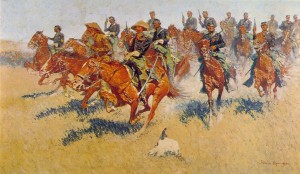

above andrea 54mm

it will be splendid, and just think,”’’ he added, ‘‘“what it will do for rheumatism!”’’

Now Jack had served in the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteers during the Civil War, and the swamps of the Chickahominy had brought him into close acquaintance with that dread disease.

As for myself, rheumatism was about the only ailment I did not have at that time, and I suppose I did not really sympathize with him. But this energetic and indomitable man mended the pump, with Fisher's help, and led the water into the house, laid a floor, set up the tub in the little square room, and behold, our sulphur bath!

After much persuasion, I tried the bath. The water flowed thick and inky black into the tub; of course the odor was beyond description, and the effect upon me was not such that I was ever willing to try it again. Jack beamed. ‘‘“How do you like it, Martha?”’’ said he. ‘‘“Isn't it fine? Why, people travel hundreds of miles to get a bath like that!”’’

I had my own opinion, but I did not wish to dampen his enthusiasm. Still, in order to protect myself in the future, I had to tell him I thought I should ordinarily prefer the river.

‘‘“Well,”’’ he said, ‘‘“there are those who will be thankful to have a bath in that water; I am going to use it every day.”’’

I remonstrated: ‘‘“How do you know what is in that inky water—and how do you dare to use it?”’’

‘‘“Oh, Fisher says it's all right; people here used to drink it years ago, but they have not done so lately, because the pump was broken down.”’’

The Washington people seemed glad to pay us the visit. Jack's eyes danced with true generosity and glee. He marked his victim; and, selecting the Staff beauty and the Paymaster's wife, he expatiated on the wonderful properties of his sulphur bath.

‘‘“Why, yes, the sooner the better,”’’ said Mrs. Martin. ‘‘“I'd give everything I have in this world, and all my chances for the next, to get a tub bath!”’’

‘‘“It will be so refreshing just before supper,”’’ said Mrs. Maynadier, who was more conservative.

So the Indian, who had put on his dark blue waistband (or sash), made from flannel, ravelled out and twisted into strands of yarn, and which showed the supple muscles of his clean-cut thighs, and who had done up an extra high pompadour in white clay, and burnished his knife, which gleamed at his waist, ushered these Washington women into a small apartment adjoining the bath-room, and turned on the inky stream into the sarcophagus.

The Staff beauty looked at the black pool, and shuddered. ‘‘“Do you use it?”’’ said she.

‘‘“Occasionally,”’’ I equivocated.

‘‘“Does it hurt the complexion?”’’ she ventured.

‘‘“Jack thinks it excellent for that,”’’ I replied.

And then I left them, directing Charley to wait, and prepare the bath for the second victim.

By and by the beauty came out. ‘‘“Where is your mirror?”’’ cried she (for our appointments were primitive, and mirrors did not grow on bushes at Ehrenberg); ‘‘“I fancy I look queer,”’’ she added, and, in truth, she did; for our water of the Styx did not seem to affiliate with the chemical properties of the numerous cosmetics used by her, more or less, all her life, but especially on the voyage, and her face had taken on a queer color, with peculiar spots here and there.

Fortunately my mirrors were neither large nor true, and she never really saw how she looked, but when she came back into the living-room, she laughed and said to Jack: ‘‘“What kind of water did you say that was? I never saw any just like it.”’’

‘‘“Oh! you have probably never been much to the sulphur springs,”’’ said he, with his most superior and crushing manner.

‘‘“Perhaps not,”’’ she replied, ‘‘“but I thought I knew something about it; why, my entire body turned such a queer color.”’’

‘‘“Oh! it always does that,”’’ said this optimistic soldier man, ‘‘“and that shows it is doing good.”’’

The Paymaster's wife joined us later. I think she had profited by the beauty's experience, for she said but little.

The Quartermaster was happy; and what if his wife did not believe in that uncanny stream which flowed somewhere from out the infernal regions, underlying

that wretched hamlet, he had succeeded in being a benefactor to two travellers at least!

We had a merry supper: cold ham, chicken, and fresh biscuit, a plenty of good Cocomonga wine, sweet milk, which to be sure turned to curds as it stood on the table, some sort of preserves from a tin, and good coffee. I gave them the best to be had in the desert—and at all events it was a change from the Chinaman's salt beef and peach pies, and they saw fresh table linen and shining silver, and accepted our simple hospitality in the spirit in which we gave it.

Alice Martin was much amused over Charley; and Charley could do nothing but gaze on her lovely features. ‘‘“Why on earth don't you put some clothes on him?”’’ laughed she, in her (below Gweronimo leads other indian chiefs i bn a parade in washington)delightful way.

I explained to her that the Indian's fashion of wearing white men's clothes was not pleasing to the eye, and told her that she must cultivate her æsthetic sense, and in a short time she would be able to admire these copper-colored creatures of Nature as much as I did.

But I fear that a life spent mostly in a large city had cast fetters around her imagination, and that the life at Fort Whipple afterwards savored too much of civilization to loosen the bonds of her soul. I saw her many times again, but she never recovered from her amazement at Charley's lack of apparel, and she never forgot the sulphur bath.ONE DAY, in the early autumn, as the “Gila” touched at Ehrenberg, on her way down river, Captain Mellon called Jack on to the boat, and, pointing to a young woman, who was about to go ashore, said: ‘‘“Now, there's a girl I think will do for your wife. She imagines she has bronchial troubles, and some doctor has ordered her to Tucson. She comes from up North somewhere. Her money has given out, and she thinks I am going to leave her here. Of course, you know I would not do that; I can take her on down to Yuma, but I thought your wife might like to have her, so I've told her she could not travel on this boat any farther without she could pay her fare. Speak to her: she looks to me like a nice sort of a girl.”’’

In the meantime, the young woman had gone ashore and was sitting upon her trunk' gazing hopelessly about. Jack approached, offered her a home and good wages, and brought her to me.

I could have hugged her for very joy, but I restrained myself and advised her to stay with us for awhile, saying the Ehrenberg climate was quite as good as that of Tucson.

She remarked quietly: ‘‘“You do not look as if it agreed with you very well, ma'am.”’’

Then I told her of my young child, and my hard journeys, and she decided to stay until she could earn enough to reach Tucson.

And so Ellen became a member of our Ehrenberg family. She was a fine, strong girl, and a very good cook, and seemed to be in perfect health. She said, however, that she had had an obstinate cough which nothing would reach, and that was why she came to Arizona. From that time, things went more smoothly. Some yeast was procured from the Mexican bake-shop, and Ellen baked bread and other things, which seemed like the greatest luxuries to us. We sent the soldier back to his company at Fort Yuma, and began to live with a degree of comfort.

I looked at Ellen as my deliverer, and regarded her coming as a special providence, the kind I had heard about all my life in New England, but had never much believed in.

After a few weeks, Ellen was one evening seized with a dreadful toothache, which grew so severe that she declared she could not endure it another hour: she must have the tooth out. ‘‘“Was there a dentist in the place?”’’

I looked at Jack: he looked at me: Ellen groaned with pain.

‘‘“Why, yes! of course there is,”’’ said this man for emergencies; ‘‘“Fisher takes out teeth, he told me so the other day.”’’

Now I did not believe that Fisher knew any more

about extracting teeth than I did myself, but I breathed a prayer to the Recording Angel, and said naught.

‘‘“I'll go get Fisher,”’’ said Jack.

Now Fisher was the steamboat agent. He stood six feet in his stockings, had a powerful physique and a determined eye. Men in those countries had to be determined; for if they once lost their nerve, Heaven save them. Fisher had handsome black eyes.

When they came in, I said: ‘‘“Can you attend to this business, Mr. Fisher?”’’

‘‘“I think so,”’’ he replied, quietly. ‘‘“The Quartermaster says he has some forceps.”’’

I gasped. Jack, who had left the room, now appeared, a box of instruments in his hand, his eyes shining with joy and triumph.

Fisher took the box, and scanned it. ‘‘“I guess they'll do,”’’ said he.

So we placed Ellen in a chair, a stiff barrack chair, with a raw-hide seat, and no arms.

It was evening.

‘‘“Mattie, you must hold the candle,”’’ said Jack. ‘‘“I'll hold Ellen, and, Fisher, you pull the tooth.”’’

So I lighted the candle, and held it, while Ellen tried, by its flickering light, to show Fisher the tooth that ached.

Fisher looked again at the box of instruments. ‘‘“Why,”’’ said he, ‘‘“these are lower jaw rollers, the

kind used a hundred years ago; and her tooth is an upper jaw.”’’

‘‘“Never mind,”’’ answered the Lieutenant, ‘‘“the instruments are all right. Fisher, you can get the tooth out, that's all you want, isn't it?”’’

The Lieutenant was impatient; and besides he did not wish any slur cast upon his precious instruments.

So Fisher took up the forceps, and clattered around amongst Ellen's sound white teeth. His hand shook, great beads of perspiration gathered on his face, and I perceived a very strong odor of Cocomonga wine. He had evidently braced for the occasion.

It was, however, too late to protest. He fastened onto a molar, and with the lion's strength which lay in his gigantic frame, he wrenched it out.

Ellen put up her hand and felt the place. ‘‘“My God! you've pulled the wrong tooth!”’’ cried she, and so he had.

I seized a jug of red wine which stood near by, and poured out a gobletful, which she drank. The blood came freely from her mouth, and I feared something dreadful had happened.

Fisher declared she had shown him the wrong tooth, and was perfectly willing to try again. I could not witness the second attempt, so I put the candle down and fled.

The stout-hearted and confiding girl allowed the second trial, and between the steamboat agent, the (below Apache woman today)

Lieutenant, and the red wine, the ailing molar was finally extracted.

This was a serious and painful occurrence. It did not cause any of us to laugh, at the time. I am sure that Ellen, at least, never saw the comical side of it.

When it was all over, I thanked Fisher, and Jack beamed upon me with: ‘‘“You see, Mattie, my case of instruments did come in handy, after all.”’’

Encouraged by success, he applied for a pannier of medicines, and the Ehrenberg citizens soon regarded him as a healer. At a certain hour in the morning, the sick ones came to his office, and he dispensed simple drugs to them and was enabled to do much good. He seemed to have a sort of intuitive knowledge about medicines and performed some miraculous cures, but acquired little of no facility in the use of the language.

I was often called in as interpreter, and with the help of the sign language, and the little I knew of Spanish, we managed to get an idea of the ailments of these poor people.

And so our life flowed on in that desolate spot, by the banks of the Great Colorado.

I rarely went outside the enclosure, except for my bath in the river at daylight, or for some urgent matter. The one street along the river was hot and sandy and neglected. One had not only to wade through the sand, but to step over the dried heads or horns or bones of animals left there to whiten

where they died, of thrown out, possibly, when some one killed a sheep of beef. Nothing decayed there, but dried and baked hard in that wonderful air and sun.

Then, the groups of Indians, squaws and half-breeds loafing around the village and the store! One never felt sure what one was to meet, and although by this time I tolerated about everything that I had been taught to think wicked or immoral, still, in Ehrenberg, the limit was reached, in the sights I saw on the village streets, too bold and too rude to be described in these pages.

The few white men there led respectable lives enough for that country. The standard was not high, and when I thought of the dreary years they had already spent there without their families, and the years they must look forward to remaining there, I was willing to reserve my judgment.WE ASKED my sister, Mrs. Penniman, to come out and spend the winter with us, and to bring her son, who was in most delicate health. It was said that the climate of Ehrenberg would have a magical effect upon all diseases of the lungs or throat. So, to save her boy, my sister made the long and arduous trip out from New England, arriving in Ehrenberg in October.

What a joy to see her, and to initiate her into the ways of our life in Arizona! Everything was new, everything was a wonder to her and to my nephew. At first, he seemed to gain perceptibly, and we had great hopes of his recovery.

It was now cool enough to sleep indoors, and we began to know what it was to have a good night's rest.

But no sooner had we gotten one part of our life comfortably arranged, before another part seemed to fall out of adjustment. Accidents and climatic conditions kept my mind in a perpetual state of unrest.

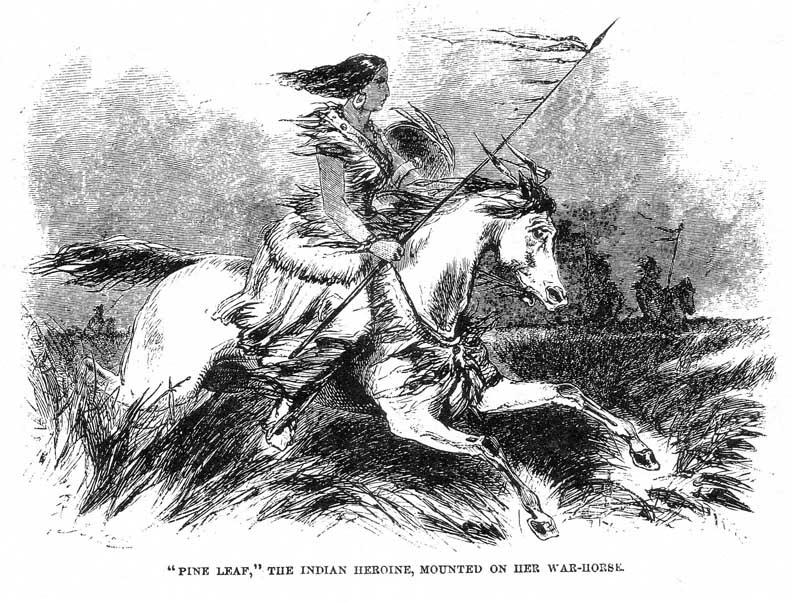

Our dining-room door opened through two small rooms into the kitchen, and one day, as I sat at the table, waiting for Jack to come in to supper, I heard a strange sort of crashing noise. Looking towards the kitchen, through the vista of open doorways, I(The life of the Indian woman, under the most favorable circumstances, is one of continual labor and unmitigated hardship. Trained to servitude from infancy, and condemned to the performance of the most menial offices, they are the servants rather than the companions of man. Upon them, therefore, fall, with peculiar severity, all those vicissitudes and accidents of savage life which impose hardships and privations beyond those that ordinarily attend the state of barbarism. Such is the case with the tribes who inhabit a sterile region, or an inhospitable climate, where the scarcity of food, and the rigor of the seasons enhance the difficulty of supporting life, and impose the' most distressing burdens on the weaker sex. The Chippeway, or, as they pronounce their own name, the Ojibway nation, is scattered along the bleak shores of our north-western lakes, over a region of barren plains, or dreary swamps, which, during the greater part of the year, are covered with snow and ice, and are, at all times, desolate and uninviting. Here the wretched Indian gleans a precarious subsistence; at one season by gathering the wild rice in the rivers and swamps, at another by fishing, and a third by hunting. Long intervals, however, occur when these resources fail, and, when exposed to absolute and hopeless want, the courage of the warrior and the ingenuity of the hunter sink into despair. The woman who, during the season of plenty, was worn down with the labor of following the hunter to the chase, carrying the game and dressing the food, now becomes the purveyor of the family, roaming the forest in search of berries, burrowing in the earth for roots, or ensnaring the lesser animals. While engaged in these various duties, she discharges, also, those of the mother, and travels over the icy plains with her infant) on her back.

saw Ellen rush to the door which led to the courtyard. She turned a livid white, threw up her hands, and cried, ‘‘“Great God! the Captain!”’’ She was transfixed with horror.

I flew to the door, and saw that the pump had collapsed and gone down into the deep sulphur well. In a second, Jack's head and hands appeared at the edge; he seemed to be caught in the dÉbris of rotten timber. Before I could get to him, he had scrambled half way out. ‘‘“Don't come near this place,”’’ he cried, ‘‘“it's all caving in!”’’

And so it seemed; for, as he worked himself up and out, the entire structure fell in, and half the corral with it, as it looked to me.

Jack escaped what might have been an unlucky bath in his sulphur well, and we all recovered our composure as best we could.

Surely, if life was dull at Ehrenberg, it could not be called exactly monotonous. We were not obliged to seek our excitement outside: we had a plenty of it, such as it was, within our walls.

My confidence in Ehrenberg, however, as a salubrious dwelling-place, was being gradually and literally undermined. I began to be distrustful of the very ground beneath my feet. Ellen felt the same way, evidently, although we did not talk much about it. She probably longed also for some of her own kind; and when, one morning, we went into the dining-room for breakfast, Ellen stood, hat on, bag in hand, at the

door. Dreading to meet my chagrin, she said: ‘‘“Goodbye, Captain; good-bye, missis; you've been very kind to me. I'm leaving on the stage for Tucson—where I first started for, you know.”’’

And she tripped out and climbed up into the dusty, rickety vehicle called “the stage.” I had felt so safe about Ellen, as I did not know that any stage line ran through the place.

And now I was in a fine plight! I took a sunshade, and ran over to Fisher's house. “Mr. Fisher, what shall I do? Ellen has gone to Tucson!”

Fisher bethought himself, and we went out together in the village. Not a woman to be found who would come to cook for us! There was only one thing to do. The Quartermaster was allowed a soldier, to assist in the Government work. I asked him if he understood cooking; he said he had never done any, but he would try, if I would show him how.

This proved a hopeless task, and I finally gave it up. Jack dispatched an Indian runner to Fort Yuma, ninety miles or more down river, begging Captain Ernest to send us a soldier-cook on the next boat.

This was a long time to wait; the inconveniences were intolerable: there were our four selves, Patrocina and Jesusíta, the soldier-clerk and the Indian, to be provided for: Patrocina prepared carni secawith peppers, a little boy came around with cuajada, a delicious sweet curd cheese, and I tried my hand at bread, following out Ellen's instructions.

How often I said to my husband, “If we must live in this wretched place, let's give up civilization and live as the Mexicans do! They are the only happy beings around here.

How often I said to my husband, “If we must live in this wretched place, let's give up civilization and live as the Mexicans do! They are the only happy beings around here.“Look at them, as you pass along the street! At nearly any hour in the day you can see them, sitting under their ramáda, their backs propped against the wall of their casa, calmly smoking cigarettes and gazing at nothing, with a look of ineffable contentment upon their features! They surely have solved the problem of life!”

But we seemed never to be able to free ourselves from the fetters of civilization, and so I struggled on.

No comments:

Post a Comment