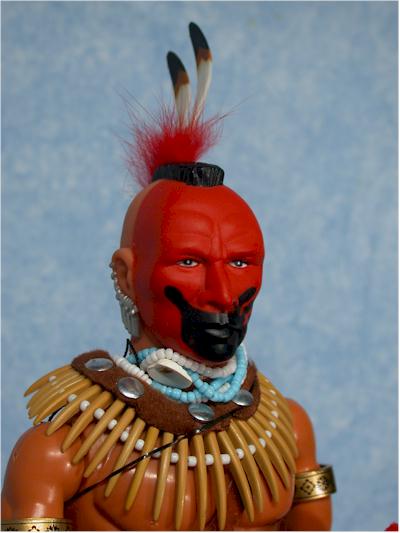

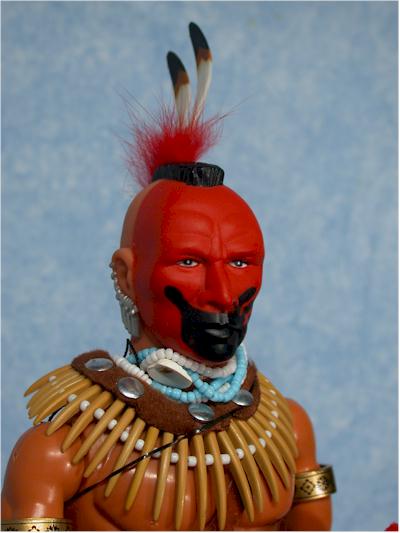

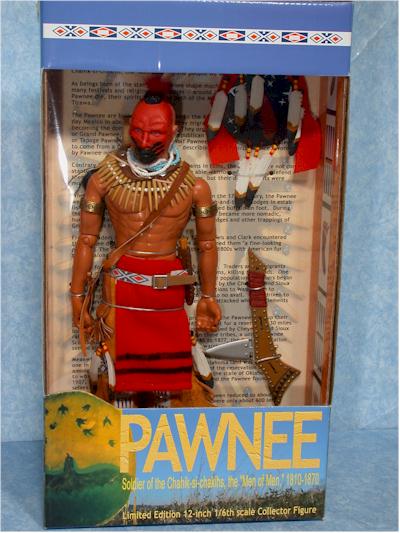

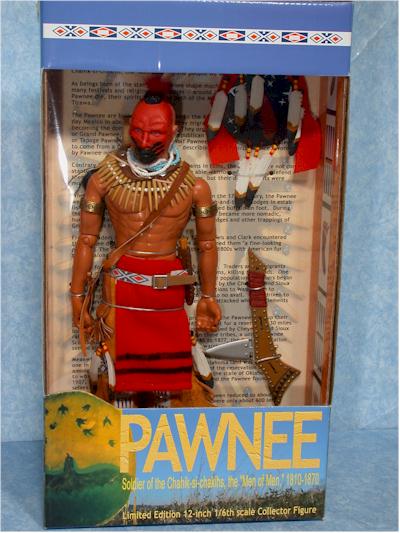

Paw nee. A confederacy belonging to the Caddoan family. The name is probably derived from parika, a horn, a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat,

nee. A confederacy belonging to the Caddoan family. The name is probably derived from parika, a horn, a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat, and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. This marked features of the Pawnee gave currency to the name and its application to cognate tribes. The people called themselves Chahiksichahiks, `men of men.'

and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. This marked features of the Pawnee gave currency to the name and its application to cognate tribes. The people called themselves Chahiksichahiks, `men of men.'

In the general northeastwardly movement of the Caddoan tribes the Pawnee seem to have brought up the rear. Their migration was not in a compact body, but in groups, whose slow progress covered long periods of time. The Pawnee tribes finally established themselves in the valley of Platte river, Nebr.,

In the general northeastwardly movement of the Caddoan tribes the Pawnee seem to have brought up the rear. Their migration was not in a compact body, but in groups, whose slow progress covered long periods of time. The Pawnee tribes finally established themselves in the valley of Platte river, Nebr., which territory, their traditions say, was acquired by conquest, but the people who were driven out are not named. It is not improbable that in making their way north east the Pawnee may have encountered one or more waves of the southward movements of Shoshonean and Athapascan tribes.

which territory, their traditions say, was acquired by conquest, but the people who were driven out are not named. It is not improbable that in making their way north east the Pawnee may have encountered one or more waves of the southward movements of Shoshonean and Athapascan tribes.

nee. A confederacy belonging to the Caddoan family. The name is probably derived from parika, a horn, a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat,

nee. A confederacy belonging to the Caddoan family. The name is probably derived from parika, a horn, a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat, and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. This marked features of the Pawnee gave currency to the name and its application to cognate tribes. The people called themselves Chahiksichahiks, `men of men.'

and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. This marked features of the Pawnee gave currency to the name and its application to cognate tribes. The people called themselves Chahiksichahiks, `men of men.'  In the general northeastwardly movement of the Caddoan tribes the Pawnee seem to have brought up the rear. Their migration was not in a compact body, but in groups, whose slow progress covered long periods of time. The Pawnee tribes finally established themselves in the valley of Platte river, Nebr.,

In the general northeastwardly movement of the Caddoan tribes the Pawnee seem to have brought up the rear. Their migration was not in a compact body, but in groups, whose slow progress covered long periods of time. The Pawnee tribes finally established themselves in the valley of Platte river, Nebr., which territory, their traditions say, was acquired by conquest, but the people who were driven out are not named. It is not improbable that in making their way north east the Pawnee may have encountered one or more waves of the southward movements of Shoshonean and Athapascan tribes.

which territory, their traditions say, was acquired by conquest, but the people who were driven out are not named. It is not improbable that in making their way north east the Pawnee may have encountered one or more waves of the southward movements of Shoshonean and Athapascan tribes. When the Siouan tribes entered Platte valley they found the Pawnee there. The geographic arrangement always observed by the four leading Pawnee tribes may give a hint of the order of their northeastward movement, or of their grouping in their traditionary southwestern home White emigration and Indian removal from the East brought devastating disease and warfare to the Pawnee and, more widely, to Indian life on the eastern Plains.

White emigration and Indian removal from the East brought devastating disease and warfare to the Pawnee and, more widely, to Indian life on the eastern Plains.  Throughout the century a series of epidemics took a steady toll on the Pawnee population. In 1849, for example, cholera killed more than a thousand individuals, and in 1852 a smallpox epidemic, only one of many, reduced the tribe.

Throughout the century a series of epidemics took a steady toll on the Pawnee population. In 1849, for example, cholera killed more than a thousand individuals, and in 1852 a smallpox epidemic, only one of many, reduced the tribe. (pawnee Buttes)Equally demoralizing was the loss of life from the unremitting attacks of their enemies, particularly the Sioux. The Pawnee had always been at war with most Plains tribes. Their only friends had been the Arikara, Mandan, and Wichita(here).

(pawnee Buttes)Equally demoralizing was the loss of life from the unremitting attacks of their enemies, particularly the Sioux. The Pawnee had always been at war with most Plains tribes. Their only friends had been the Arikara, Mandan, and Wichita(here). They had also enjoyed intermittent peace with the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto, but only because they had inspired fear in them. With all others, particularly the large nomadic ones, there was perpetual conflict. After the treaty of 1833,

They had also enjoyed intermittent peace with the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto, but only because they had inspired fear in them. With all others, particularly the large nomadic ones, there was perpetual conflict. After the treaty of 1833,  however, the Pawnee gave up their weapons, renounced warfare, and agreed to take up new lives as agrarians, ostensibly to be protected by the U.S. government. The effect of this new life of dependency, combined with severe population loss from disease, left the Pawnee vulnerable to their enemies, primarily the Sioux, who vowed a war of extermination. For forty years after that treaty the weaponless and unprotected Pawnee endured constant attacks by Sioux war parties that inflicted a major loss of life. Finally, in 1874 the tribe began a two-year removal to Indian Territory, where the Pawnee began new lives.

however, the Pawnee gave up their weapons, renounced warfare, and agreed to take up new lives as agrarians, ostensibly to be protected by the U.S. government. The effect of this new life of dependency, combined with severe population loss from disease, left the Pawnee vulnerable to their enemies, primarily the Sioux, who vowed a war of extermination. For forty years after that treaty the weaponless and unprotected Pawnee endured constant attacks by Sioux war parties that inflicted a major loss of life. Finally, in 1874 the tribe began a two-year removal to Indian Territory, where the Pawnee began new lives.

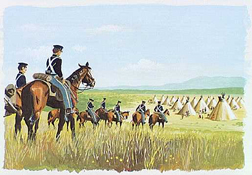

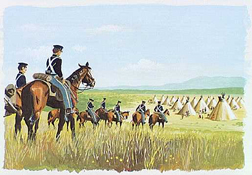

Pressure from the Sioux motivated the Pawnee to furnish scouts who served with the U.S. Army during the Plains Indian wars. The first enlistment comprised ninety-five scouts who served in the 1865-66 Powder River Expedition against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, a battalion of four companies of Pawnee scouts was enlisted to protect workers engaged in constructing the Union Pacific Railroad's transcontinental line through Nebraska and Wyoming during the late 1860s. In 1871 the scouts were mustered out, but again during the 1876-77 campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne, scouts were enlisted.

The first enlistment comprised ninety-five scouts who served in the 1865-66 Powder River Expedition against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, a battalion of four companies of Pawnee scouts was enlisted to protect workers engaged in constructing the Union Pacific Railroad's transcontinental line through Nebraska and Wyoming during the late 1860s. In 1871 the scouts were mustered out, but again during the 1876-77 campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne, scouts were enlisted.

White emigration and Indian removal from the East brought devastating disease and warfare to the Pawnee and, more widely, to Indian life on the eastern Plains.

White emigration and Indian removal from the East brought devastating disease and warfare to the Pawnee and, more widely, to Indian life on the eastern Plains.  Throughout the century a series of epidemics took a steady toll on the Pawnee population. In 1849, for example, cholera killed more than a thousand individuals, and in 1852 a smallpox epidemic, only one of many, reduced the tribe.

Throughout the century a series of epidemics took a steady toll on the Pawnee population. In 1849, for example, cholera killed more than a thousand individuals, and in 1852 a smallpox epidemic, only one of many, reduced the tribe. (pawnee Buttes)Equally demoralizing was the loss of life from the unremitting attacks of their enemies, particularly the Sioux. The Pawnee had always been at war with most Plains tribes. Their only friends had been the Arikara, Mandan, and Wichita(here).

(pawnee Buttes)Equally demoralizing was the loss of life from the unremitting attacks of their enemies, particularly the Sioux. The Pawnee had always been at war with most Plains tribes. Their only friends had been the Arikara, Mandan, and Wichita(here). They had also enjoyed intermittent peace with the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto, but only because they had inspired fear in them. With all others, particularly the large nomadic ones, there was perpetual conflict. After the treaty of 1833,

They had also enjoyed intermittent peace with the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto, but only because they had inspired fear in them. With all others, particularly the large nomadic ones, there was perpetual conflict. After the treaty of 1833,  however, the Pawnee gave up their weapons, renounced warfare, and agreed to take up new lives as agrarians, ostensibly to be protected by the U.S. government. The effect of this new life of dependency, combined with severe population loss from disease, left the Pawnee vulnerable to their enemies, primarily the Sioux, who vowed a war of extermination. For forty years after that treaty the weaponless and unprotected Pawnee endured constant attacks by Sioux war parties that inflicted a major loss of life. Finally, in 1874 the tribe began a two-year removal to Indian Territory, where the Pawnee began new lives.

however, the Pawnee gave up their weapons, renounced warfare, and agreed to take up new lives as agrarians, ostensibly to be protected by the U.S. government. The effect of this new life of dependency, combined with severe population loss from disease, left the Pawnee vulnerable to their enemies, primarily the Sioux, who vowed a war of extermination. For forty years after that treaty the weaponless and unprotected Pawnee endured constant attacks by Sioux war parties that inflicted a major loss of life. Finally, in 1874 the tribe began a two-year removal to Indian Territory, where the Pawnee began new lives.

Pressure from the Sioux motivated the Pawnee to furnish scouts who served with the U.S. Army during the Plains Indian wars.

The first enlistment comprised ninety-five scouts who served in the 1865-66 Powder River Expedition against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, a battalion of four companies of Pawnee scouts was enlisted to protect workers engaged in constructing the Union Pacific Railroad's transcontinental line through Nebraska and Wyoming during the late 1860s. In 1871 the scouts were mustered out, but again during the 1876-77 campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne, scouts were enlisted.

The first enlistment comprised ninety-five scouts who served in the 1865-66 Powder River Expedition against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, a battalion of four companies of Pawnee scouts was enlisted to protect workers engaged in constructing the Union Pacific Railroad's transcontinental line through Nebraska and Wyoming during the late 1860s. In 1871 the scouts were mustered out, but again during the 1876-77 campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne, scouts were enlisted.

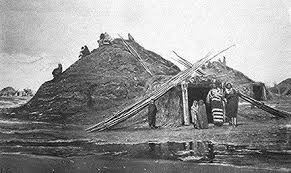

From the treaty of 1833 until their move to Indian Territory, Pawnees were also under progressively increasing pressure to change from their traditional lifestyle to the new agrarian one represented by white farmers. Missionary efforts began in 1831, with the arrival of the Presbyterians John Dunbar and Samuel Allis. Government farmers soon settled among the Pawnees as well, and Allis opened a school for Pawnee children. Until 1860, however, most of these efforts at changing Pawnee life were desultory and ineffective. After the tribe settled on a reservation, however, government efforts at acculturation intensified. Conscious of the gradual disappearance of the buffalo, many Pawnees were becoming more amenable to an agricultural way of life by individual families and to education. Nevertheless, right up to their removal from Nebraska, they still clung to their village life. Most people lived in earth lodges, cultivated corn, beans, and squash in the traditional manner, and depended on the buffalo for part of their subsistence.

DER BUNTE ROCK Pawnee scout

DER BUNTE ROCK Pawnee scout In 1874 the Pawnee gave up their Nebraska reservation over a three-year period moved to Oklahoma. Meanwhile, the Pawnee agent had selected a new reservation for them on Cherokee land between the forks of the Arkansas and Cimarron rivers, south of the Osage Reservation. The bulk of this land comprises contemporary Pawnee County. After tribal leaders accepted the land, the tribe, with a population of some 2,000, settled into a pattern of life much like the one they had known in Nebraska. Each band settled on a large, separate tract of land assigned to it and, initially, began cooperatively to farm the band tract. For a short time an attenuated form of their old village life was maintained; chiefs, priests, and doctors continued to organize Pawnee social, economic, and religious life. Nevertheless, many younger, progressive Pawnees soon began to move onto individual farms during their first decade in Indian Territory. By 1890 most of the Skiris and a large proportion of the Chawis were living in houses on their own farms, dressing like contemporary whites, and speaking English in daily life. (below Pawnee Buttes)

By the close of the century, then, Pawnee culture fundamentally had changed. The symbols of the old were now by and large vestiges. Village life had been replaced by life on individual farms; a mixed horticultural-hunting subsistence pattern had given way to agriculture and government rations; the authority of chiefs had been replaced by that of the agent; and religious ceremonies and the knowledge of sacred bundles was rapidly disappearing as the priests who possessed that knowledge died and no successors came forward. Doctors' dances were to continue in attenuated form for several decades, but after 1878 the protracted late-summer doctors' dance, in which the doctors demonstrated their powers, ceased.

During the early years on their new reservation, the Pawnees tried to provide for themselves by farming. The produce, however, proved inadequate because of natural misfortunes. Since no more than one-third of the reservation was suited for cultivation, the government tried to develop a stock-raising program, but that ended in failure in 1882. In that same year, as a result of the Allotment Act, individual families were encouraged to relocate on individual farms. In 1890 most Skiris and a large proportion of Chawis lived in houses on their own farms, and during the decade most Pitahawiratas and Kitkahahkis moved onto their own land as well. At the same time agency officials relentlessly attacked many Pawnee social customs: polygamous marriages, dances, gambling, and feasting. By 1890 Pawnees were relatively prosperous materially and had adopted most of the material culture of their white neighbors. However, over the first three decades of their new residence in Indian Territory, the Pawnee people experienced poor health, coupled with inadequate sanitation and health care. As a result, the population reached a record low of 629 individuals in 1901 and did not begin to recover until the 1930s.

On his way west in June 1842 explorer John C. Frémont encountered a cluster of burned and blackened lodges scattered in an open wood on the east bank of the Vermillion River, just north of the Kansas River in present-day Kansas. What Frémont saw were the results of a bitter event in a long and sometimes bloody war between the Kansa (or Kaw) and Pawnee people.

Situated near Belvue, this abandoned Kansa village had been attacked and burned earlier that spring by the Pawnees.The burning of the village was in retaliation for a massacre of Pawnees perpetrated by Kansa warriors in December 1840. Sixty-five Kansa warriors had surprised a Pawnee camp whose warriors had left on a buffalo hunt. The Kansa killed more than 70 people, mostly women and children, and captured 11.

The two tribes had been enemies longer than anyone could remember. From the 1500s, if not earlier, the Pawnees had lived and hunted in present-day Nebraska and Kansas. The Pawnees were organized into four independent bands: the Chaui, Pitahauerat, Skidi, and Kitkahahki, the latter having been victimized by the Kansas in the 1840 attack.

By 1700 the Kansas had migrated from the Ohio River Valley and established a village on the west bank of the Missouri River in present Doniphan County. At the time of the massacre of Pawnees, the Kansas were living in three villages—the Vermillion River village and two others near present-day Topeka.

The Pawnees were the dominant power of the Central Plains by the 1800s. Their numerous earth lodge villages were located near the Loup and Platte Rivers in present Nebraska and along the Republican River in what is now Kansas. Their hunting grounds covered much of the High Plains, and this meant conflict with almost every other plains tribe including the Kansa.

Their hunting grounds covered much of the High Plains, and this meant conflict with almost every other plains tribe including the Kansa.

Both cultural practices and historical events fueled the conflict between the two tribes. The Pawnees and Kansas encouraged their young men in the practice of the martial spirit. Those warriors performing daring feats in battle and stealing horses from enemy tribes won honors and gained status in the tribe. Retaliation for violence and attacks was part of the culture for both tribes.

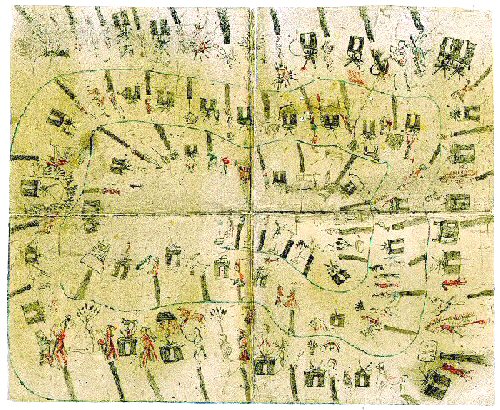

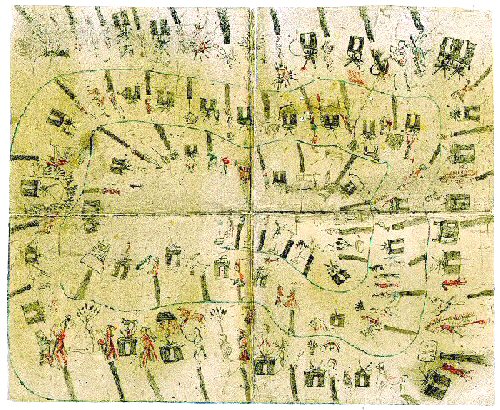

kiowa calender

The arrival of Euro-Americans brought the fur trade to the plains, and competition between the tribes for the harvest of pelts—often encouraged by the traders for business reasons—became fierce. By the late 1700s Pawnee and Kansa warriors had become expert horsemen and were better able to travel long distances to raid each other. Most of these raids were essentially horse-stealing expeditions, but some escalated into violent encounters.

The U.S. government frequently attempted to arrange truces between the Pawnees and the Kansas, but these efforts met with little success. In 1830 pressure from the Kansas and their Osage allies forced the Kitkahahki band to abandon its village in present Republic County and to rejoin the other Pawnee bands to the north in the Platte River Valley.

By the 1870s, however, both the Pawnees and the Kansas were reeling from poverty, disease, and the loss of their lands. In June 1872 a large band of Pawnees traveled from their Nebraska reservation to smoke the pipe with the Kansas on their Council Grove reservation. The week long celebration concluded with an exchange of gifts and expressions of good will between the ancient enemies. At long last the Pawnees and the Kansas were at peace.

One year later the Kansas were removed to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma); the Pawnees were relocated there in 1876.

The Pawnee Nation at present numbers close to 2,500 members with many residing in the Pawnee, Oklahoma area. The Pawnees are very proud of their past and have many annual celebrations to honor their history. They also have a very active language program that helps keep their culture alive.

Today the Kansa tribal organization, known as the Kaw Nation, has a membership of approximately 2,600. Headquartered in Kaw City, Oklahoma, the Kaw Nation provides its members with many social, cultural, and health care benefits under the governance of the Kaw Executive Council.

The Kansas retain vital ties to their homelands in Kansas. In early 2000 the Kaw Nation purchased approximately 170 acres of former reservation land about four miles southeast of Council Grove. Named for their great chief, the Al-le-ga

No comments:

Post a Comment