Ask any audience attending a lecture on Robin Hood the following questions: to each there will be an entirely predictable answer.

Ask any audience attending a lecture on Robin Hood the following questions: to each there will be an entirely predictable answer.  \ Who has never read, heard or seen a tale of Robin Hood? Answer: no-one. \ Who has read the stories as an adult other than to children? Answer: no-one.

\ Who has never read, heard or seen a tale of Robin Hood? Answer: no-one. \ Who has read the stories as an adult other than to children? Answer: no-one. \ Who has ever read the stories in the original versions? \ Answer: no-one. \

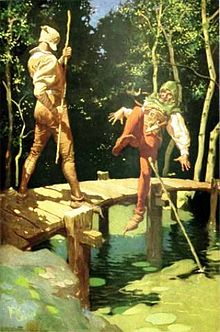

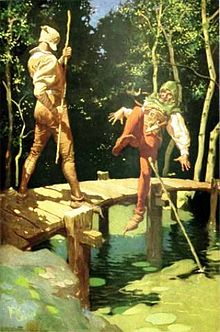

\ Who has ever read the stories in the original versions? \ Answer: no-one. \EE9s2uiO)-BR!6TTEHQg~~60_12.JPG) In one form or another, the tales have been told to children by adults who themselves learned them as children. That holds good for the last two hundred years, probably for much longer.

In one form or another, the tales have been told to children by adults who themselves learned them as children. That holds good for the last two hundred years, probably for much longer.  It is thus that the legend has been transmitted and transmuted; and has endured.

It is thus that the legend has been transmitted and transmuted; and has endured. - Professor. J.C. Holt, Robin HooThe Robin Hood legends form part of a corpus of outlaw stories which date from around the reign of King John. Two other key outlaws, Fulk fitzWarin and Eustace the Monk, were historical figures whose lives can be clearly identified at this time, but Robin Hood himself is much more problematical.

- Professor. J.C. Holt, Robin HooThe Robin Hood legends form part of a corpus of outlaw stories which date from around the reign of King John. Two other key outlaws, Fulk fitzWarin and Eustace the Monk, were historical figures whose lives can be clearly identified at this time, but Robin Hood himself is much more problematical.

What is striking about these stories is that they reveal that, in an age when the Rule of Law was respected as the foundation of good government, those who put themselves outside the law had become popular heroes. This is in complete contrast to public perceptions of the outlaw at the beginning of King Henry II's reign, and shows that the existing order had come to be regarded as tyrannical. Tyranny was the abuse of law.

If the existing order was founded on the arbitrary will of evil men who could twist the law to their own ends, then it was the role of the outlaw to seek redress and justice by other means. In a violent age, these means were invariably violent. Robin Hood  and his contemporaries were cunning, merciless and often brutal (in one instance Much the Miller's Son murders a monk's page to prevent him giving them away); but by the codes of their time, they were also honourable.

and his contemporaries were cunning, merciless and often brutal (in one instance Much the Miller's Son murders a monk's page to prevent him giving them away); but by the codes of their time, they were also honourable.

and his contemporaries were cunning, merciless and often brutal (in one instance Much the Miller's Son murders a monk's page to prevent him giving them away); but by the codes of their time, they were also honourable.

and his contemporaries were cunning, merciless and often brutal (in one instance Much the Miller's Son murders a monk's page to prevent him giving them away); but by the codes of their time, they were also honourable. In all these tales, the forest figures prominently. The forest in the Middle Ages included very extensive areas of cultivated land as well as wood and waste land. They were the private preserve of the king and his officers, and were protected by a harsh series of forest laws, against which there could be no appeal - not even to the ecclesiastical courts..

In all these tales, the forest figures prominently. The forest in the Middle Ages included very extensive areas of cultivated land as well as wood and waste land. They were the private preserve of the king and his officers, and were protected by a harsh series of forest laws, against which there could be no appeal - not even to the ecclesiastical courts..

The origins of the Robin Hood legend are very obscure. The first literary reference to Robin Hood comes from a passing reference in Piers Plowman, written some time around 1377, and the main body of tales date from the fifteenth century. Q~~60_12.JPG) These are found in the tales of Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450); The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode (written down c.1492-1510, but probably composed c.1400); and the C17th Percy Folio, which contains three C15th stories: Robin Hoode his Death, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne and Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar.

These are found in the tales of Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450); The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode (written down c.1492-1510, but probably composed c.1400); and the C17th Percy Folio, which contains three C15th stories: Robin Hoode his Death, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne and Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar.

Q~~60_12.JPG) These are found in the tales of Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450); The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode (written down c.1492-1510, but probably composed c.1400); and the C17th Percy Folio, which contains three C15th stories: Robin Hoode his Death, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne and Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar.

These are found in the tales of Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450); The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode (written down c.1492-1510, but probably composed c.1400); and the C17th Percy Folio, which contains three C15th stories: Robin Hoode his Death, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne and Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar.

Within these literary references, there is nothing to suggest that Robin Hood should date to the time of King John: in fact the only king mentioned is 'Edward our comely king', which probably refers to a visit to Nottingham of King Edward II in 1324. Yet a court roll from Berkshire indicates that the legend of Robin Hood dates much earlier than this.The King's Remembrancer's Memoranda Roll of Easter 1262 notes the pardoning of the prior of Sandleford for seizing without warrant the chattels of one William

which probably refers to a visit to Nottingham of King Edward II in 1324. Yet a court roll from Berkshire indicates that the legend of Robin Hood dates much earlier than this.The King's Remembrancer's Memoranda Roll of Easter 1262 notes the pardoning of the prior of Sandleford for seizing without warrant the chattels of one William  Robehod, fugitive. This case can be cross-referenced with the roll of the Justices in Eyre in Berkshire in 1261, in which a criminal gang is outlawed, including William son of Robert le Fevere, whose chattels were seized without warrant by the prior of Sandleford.

Robehod, fugitive. This case can be cross-referenced with the roll of the Justices in Eyre in Berkshire in 1261, in which a criminal gang is outlawed, including William son of Robert le Fevere, whose chattels were seized without warrant by the prior of Sandleford.

which probably refers to a visit to Nottingham of King Edward II in 1324. Yet a court roll from Berkshire indicates that the legend of Robin Hood dates much earlier than this.The King's Remembrancer's Memoranda Roll of Easter 1262 notes the pardoning of the prior of Sandleford for seizing without warrant the chattels of one William

which probably refers to a visit to Nottingham of King Edward II in 1324. Yet a court roll from Berkshire indicates that the legend of Robin Hood dates much earlier than this.The King's Remembrancer's Memoranda Roll of Easter 1262 notes the pardoning of the prior of Sandleford for seizing without warrant the chattels of one William  Robehod, fugitive. This case can be cross-referenced with the roll of the Justices in Eyre in Berkshire in 1261, in which a criminal gang is outlawed, including William son of Robert le Fevere, whose chattels were seized without warrant by the prior of Sandleford.

Robehod, fugitive. This case can be cross-referenced with the roll of the Justices in Eyre in Berkshire in 1261, in which a criminal gang is outlawed, including William son of Robert le Fevere, whose chattels were seized without warrant by the prior of Sandleford.

This is merely the earliest of several such references to Robehods or Robynhods, most of them outlaws, after the mid-C13th, and it provides a usefulterminus ante quem for the existence of the legend. Robin Hood must have existed before 1261 for his name to have been misused in such a way.This William son of Robert and William Robehod were certainly one and the same, and some clerk during transcription had changed the name. It follows that the man who changed the name knew of the legend and equated the name of Robin Hood with outlawry.

We should not be surprised at such misuse. There are numerous cases in the C13th & C14th of outlaws deliberately taking on the pseudonyms of Robin Hood and Little John, and it seems likely that the original Friar Tuck who got accreted to the legend was one Robert Stafford who was active in Sussex between 1417 and 1429. Yet this in itself indicates just how difficult it is to tie Robin Hood down, since each misuse of the legend adds details of its own.It is simply not possible to locate the historical Robin Hood with any certainty. The literary corpus very firmly locates the activities of the outlaw in the north, around the Barnsdale area and Sherwood Forest.

EUSTACE

He was born in 1170 and for a time during his childhood (though it is not quite certain just how long), Eustace lived in a monastery. While this didn’t last very long, and it doesn’t seem that he really “took” to the religion, it at least explains where his later moniker rose from.

After this, between the years of 1202 and 1204 (he was already 32 years old at this point, so clearly much of his early history is lost), Eustace the Monk went to work in the household of the Count of Boulogne (the city in France in which he had been born).

As the legend goes, it is here that he got his start in some of the shadier aspects of life.Eustace was accused by the Count, for one reason or another, of improper stewardship of his possessions. Having been accused (and most likely guilty), Eustace fled the city as an outlaw. He would never again live a proper or legal life.

So what did Eustace the Monk do in this sticky situation? Why, just what any rational man would do.

He became a pirate.

Somehow, Eustace gained control of a ship and a crew. He was so good at what he did, sailing as a mercenary for hire throughout the British Channel, that eventually he was commanding an entire fleet.

This is how things would remain for the rest of Eustace the Monk's life, which was surely full of many great stories and legends which have long since been lost and forgotten.

At this point, Eustace and his fleet acted on behalf of the highest bidder. For a considerable period of time (the 8 years between 1205 to 1212), the highest bidder for the fleet was King John of England  (that same King John whom the villain in most modern adaptations of the tales of Robin Hood, usually called Prince John, are based – the brother of King Richard the Lionheart

(that same King John whom the villain in most modern adaptations of the tales of Robin Hood, usually called Prince John, are based – the brother of King Richard the Lionheart ), who was at the time in a war against King Phillip II of France (Eustace’s home country).

), who was at the time in a war against King Phillip II of France (Eustace’s home country).

Eustace's fleet performed many duties during this war, pillaging and plundering French coastal towns and destroying French ships. King John felt he needed Eustace's ships enough that when the pirate’s ships began to raid English towns as well, King John went so far as to issue him a full pardon.

But, like any good pirate, Eustace the Monk's relationship with England didn't last long. In 1212, after the British began to seize several of the island assets he had claimed in the English Channel, Eustace decided to side with the French instead. In 1215, a Civil War broke out in England, which France took as their opportunity to invade, with Eustace the Monk's help.

And this is how Eustace the Monk made enemies of both England and France and became the most feared and  despised of men.

despised of men.

despised of men.

despised of men.

In early 1217, as Eustace and his fleet were transporting French troops to England for an invasion, they were attacked by  British ships. While Eustace's ships and men were at last bested (so great was the British fleet), he himself escaped, though only temporarily.

British ships. While Eustace's ships and men were at last bested (so great was the British fleet), he himself escaped, though only temporarily.

British ships. While Eustace's ships and men were at last bested (so great was the British fleet), he himself escaped, though only temporarily.

British ships. While Eustace's ships and men were at last bested (so great was the British fleet), he himself escaped, though only temporarily.

In August of that same year, Eustace was finally captured by the British during the Battle of Sandwich (one of two Battles  of Sandwich during the medieval period).

of Sandwich during the medieval period).

of Sandwich during the medieval period).

of Sandwich during the medieval period).

Under the command of William d'Aubigney, 3rd Earl of Arundel, Eustace the Monk was finally captured and there, just off  the coast of Sandwich, England (hence the name of the battle), he was beheaded.

the coast of Sandwich, England (hence the name of the battle), he was beheaded.

the coast of Sandwich, England (hence the name of the battle), he was beheaded.

the coast of Sandwich, England (hence the name of the battle), he was beheaded.

Not a surprising end to this important, yet mostly unknown, character from the history of the middle ages.

References:

There was an upsurge in piracy during the Hundred Years’ War (circa 1337 to 1453). The dukes of Mecklenburg hired German seamen, who became known as Victual Brothers (Vitalienbrüder) because they supplied food to Stockholm while the Danes besieged it. In reality, though, they were sevore (sea robbers), and since they received no wages, they survived by plundering ships of the Hanse. Once they boarded a vessel, they slew anyone who had dared to resist them. The rest they put in barrels, nailed shut the lids, and stowed them in the hold until they could be ransomed. But the Vitalienbrüder weren’t always successful:

because they supplied food to Stockholm while the Danes besieged it. In reality, though, they were sevore (sea robbers), and since they received no wages, they survived by plundering ships of the Hanse. Once they boarded a vessel, they slew anyone who had dared to resist them. The rest they put in barrels, nailed shut the lids, and stowed them in the hold until they could be ransomed. But the Vitalienbrüder weren’t always successful:

because they supplied food to Stockholm while the Danes besieged it. In reality, though, they were sevore (sea robbers), and since they received no wages, they survived by plundering ships of the Hanse. Once they boarded a vessel, they slew anyone who had dared to resist them. The rest they put in barrels, nailed shut the lids, and stowed them in the hold until they could be ransomed. But the Vitalienbrüder weren’t always successful:

because they supplied food to Stockholm while the Danes besieged it. In reality, though, they were sevore (sea robbers), and since they received no wages, they survived by plundering ships of the Hanse. Once they boarded a vessel, they slew anyone who had dared to resist them. The rest they put in barrels, nailed shut the lids, and stowed them in the hold until they could be ransomed. But the Vitalienbrüder weren’t always successful:

, and nine others in the fourteenth century. Like its counterpart, the league’s mission was to protect local shipping from pirates while encouraging trade, but its members tended toward piracy, attacking any and all ships that refused to pay protection money.

, and nine others in the fourteenth century. Like its counterpart, the league’s mission was to protect local shipping from pirates while encouraging trade, but its members tended toward piracy, attacking any and all ships that refused to pay protection money.

The English Channel, the North Sea, and the Baltic Sea were not the only waters where pirates hunted during the Middle Ages. They also plagued the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Adriatic Seas. Byzantium employed pirates and their captains to further its reach. In the 1260s, the emperor primarily used the sea rogues for his navyOne of the earliest pirates who engraved his name on the historical record was Margaritone of Brindisi, an Italian knight

known as “The New Neptune.” He allied himself with Sicily’s Norman rulers and eventually became that island’s Grand Admiral. In 1185 he proclaimed himself Count of Cephalonia and Zante and used the island for a privateering base. While participating in the defense of Naples in 1194, he was captured by troops of the Holy Roman Emperor and spent the remainder of his days in a German prison.

known as “The New Neptune.” He allied himself with Sicily’s Norman rulers and eventually became that island’s Grand Admiral. In 1185 he proclaimed himself Count of Cephalonia and Zante and used the island for a privateering base. While participating in the defense of Naples in 1194, he was captured by troops of the Holy Roman Emperor and spent the remainder of his days in a German prison.

1261. Quite frankly, I wouldn't stake my reputation on it. John Major's dating is purely arbitrary, and two of his contemporaries give Robin's dates as 1283-5 or 1266; while the full date on the Kirklees gravestone, 25 Kalends Decembris 1247, is impossible as there is no 25 Kalends in the Roman calendar.This is the only possible original bearing the name of Robin Hood who is know to have been an outlaw (there are other Hoods in Wakefield, but none of them seem to have been fugitives). An epitaph recorded by Thomas Gale in 1702 recorded that a grave purporting to be that of Robin Hood lay at Kirklees (where the legend claims he was killed), dated to 1247.

1261. Quite frankly, I wouldn't stake my reputation on it. John Major's dating is purely arbitrary, and two of his contemporaries give Robin's dates as 1283-5 or 1266; while the full date on the Kirklees gravestone, 25 Kalends Decembris 1247, is impossible as there is no 25 Kalends in the Roman calendar.This is the only possible original bearing the name of Robin Hood who is know to have been an outlaw (there are other Hoods in Wakefield, but none of them seem to have been fugitives). An epitaph recorded by Thomas Gale in 1702 recorded that a grave purporting to be that of Robin Hood lay at Kirklees (where the legend claims he was killed), dated to 1247.

ation his true identity had been obsured

ation his true identity had been obsured was furious when he discovered that a northern robber, Piers de Bruville, was using Fulk's name to coFulk is in fact a far more interesting character than Robin Hood, with a personal link to King John. He was a childhood friend of John's, but their relationship was a stormy one. One day, whilst playing chess, John broke the chessboard over Fulk's head.He ambushed Piers and his men in a house they were raiding and forced Piers to tie his men to their seats and behead every one of them with his own hands. When the ugly task was finished, Fulk struck off Piers' head himself, saying: 'None shall ever charge me falsely with theft.'

was furious when he discovered that a northern robber, Piers de Bruville, was using Fulk's name to coFulk is in fact a far more interesting character than Robin Hood, with a personal link to King John. He was a childhood friend of John's, but their relationship was a stormy one. One day, whilst playing chess, John broke the chessboard over Fulk's head.He ambushed Piers and his men in a house they were raiding and forced Piers to tie his men to their seats and behead every one of them with his own hands. When the ugly task was finished, Fulk struck off Piers' head himself, saying: 'None shall ever charge me falsely with theft.' but when John came to power, he gave the honour to Fulk's old enemy, Morys fitzRoger. Fulk reacted by murdering Morys and fleeing into outlawry, where he levied war against John and his agents for 3 years.

but when John came to power, he gave the honour to Fulk's old enemy, Morys fitzRoger. Fulk reacted by murdering Morys and fleeing into outlawry, where he levied war against John and his agents for 3 years.

Nottingham, Fulk lures the king into the forest, where he kidnaps him, invites him to dinner and eventually lets him go. These parallels are not mere coincidences, they are exact analogies,

Nottingham, Fulk lures the king into the forest, where he kidnaps him, invites him to dinner and eventually lets him go. These parallels are not mere coincidences, they are exact analogies,  and they share much of the same mythological basis as the earlier tales of Hereward the Wake (who himself uses disguises and trickery). If our dating of Robin Hood is correct, then the

and they share much of the same mythological basis as the earlier tales of Hereward the Wake (who himself uses disguises and trickery). If our dating of Robin Hood is correct, then the  tales are contemporaneous, and what we can see here is the development of a popular mythology which eulogises those men who stood out against the excesses of John's rule.Both of these interweave magical incidents and anecdotes reminiscent of the tales of Hereward the Wake; but they also contain stories which can be directly compared to some of the tales of

tales are contemporaneous, and what we can see here is the development of a popular mythology which eulogises those men who stood out against the excesses of John's rule.Both of these interweave magical incidents and anecdotes reminiscent of the tales of Hereward the Wake; but they also contain stories which can be directly compared to some of the tales of  Robin Hood. Eustace, like Robin, disguises himself as a potter in order to confound his enemies: Fulk disguises himself as a charcoal-burner. Fulk robs the king's merchants, at the king's expense, and forces them to dine with him.

Robin Hood. Eustace, like Robin, disguises himself as a potter in order to confound his enemies: Fulk disguises himself as a charcoal-burner. Fulk robs the king's merchants, at the king's expense, and forces them to dine with him.

Northampton and stuck his head on the city gates. By the time of John, all this has changed.

Northampton and stuck his head on the city gates. By the time of John, all this has changed. but they do beat the strong to help the weak. This explains the enduring popularity of the Robin Hood legends; they are the little man's way of striking back.

but they do beat the strong to help the weak. This explains the enduring popularity of the Robin Hood legends; they are the little man's way of striking back.

No comments:

Post a Comment