The troubles at the Siletz and Yaquina Bay were settled without further excitement by the arrival in due time of plenty of food,  and as the buildings, at fort haskins (below)were so near completion that my services as quartermaster were no longer needed,

and as the buildings, at fort haskins (below)were so near completion that my services as quartermaster were no longer needed, I was ordered to join my own company at Fort Yamhill, where Captain Russell was still in command.

I was ordered to join my own company at Fort Yamhill, where Captain Russell was still in command. I returned to that place in May, 1857, and at a period a little later,

I returned to that place in May, 1857, and at a period a little later, in consequence of the close of hostilities in southern Oregon, the Klamaths

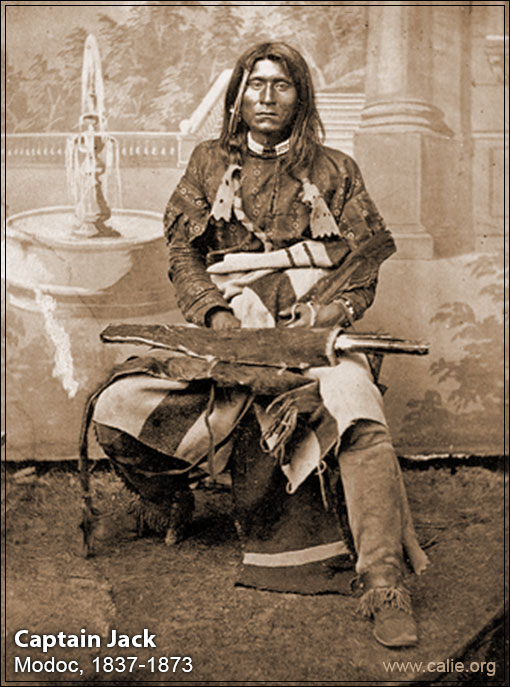

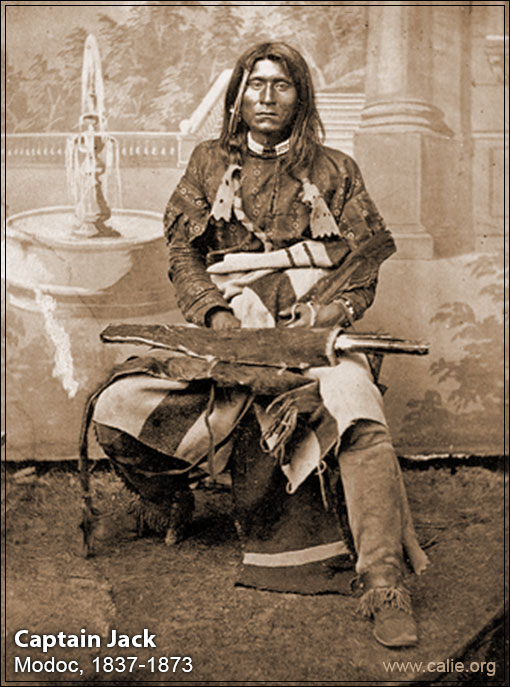

in consequence of the close of hostilities in southern Oregon, the Klamaths and Modocs

and Modocs were sent back to their own country, to that section in which occurred,

were sent back to their own country, to that section in which occurred, in 1873, the disastrous war with the latter tribe. This reduced considerably the number of Indians at the Grande Ronde, but as those remaining were still

in 1873, the disastrous war with the latter tribe. This reduced considerably the number of Indians at the Grande Ronde, but as those remaining were still  somewhat unruly, from the fact that many questions requiring adjustment were constantly arising between the different bands,

somewhat unruly, from the fact that many questions requiring adjustment were constantly arising between the different bands,  the agent and the officers at the post were kept pretty well occupied. Captain Russell assigned to me the

the agent and the officers at the post were kept pretty well occupied. Captain Russell assigned to me the  special work of keeping up the police control, and as I had learned at an early day to speak Chinook (the "court language" among the coast tribes)

special work of keeping up the police control, and as I had learned at an early day to speak Chinook (the "court language" among the coast tribes) almost as well as the Indians themselves, I was thereby enabled to steer my way successfully on many critical occasions.

almost as well as the Indians themselves, I was thereby enabled to steer my way successfully on many critical occasions.

and as the buildings, at fort haskins (below)were so near completion that my services as quartermaster were no longer needed,

and as the buildings, at fort haskins (below)were so near completion that my services as quartermaster were no longer needed, I was ordered to join my own company at Fort Yamhill, where Captain Russell was still in command.

I was ordered to join my own company at Fort Yamhill, where Captain Russell was still in command. I returned to that place in May, 1857, and at a period a little later,

I returned to that place in May, 1857, and at a period a little later, in consequence of the close of hostilities in southern Oregon, the Klamaths

in consequence of the close of hostilities in southern Oregon, the Klamaths and Modocs

and Modocs were sent back to their own country, to that section in which occurred,

were sent back to their own country, to that section in which occurred, in 1873, the disastrous war with the latter tribe. This reduced considerably the number of Indians at the Grande Ronde, but as those remaining were still

in 1873, the disastrous war with the latter tribe. This reduced considerably the number of Indians at the Grande Ronde, but as those remaining were still  somewhat unruly, from the fact that many questions requiring adjustment were constantly arising between the different bands,

somewhat unruly, from the fact that many questions requiring adjustment were constantly arising between the different bands,  the agent and the officers at the post were kept pretty well occupied. Captain Russell assigned to me the

the agent and the officers at the post were kept pretty well occupied. Captain Russell assigned to me the  special work of keeping up the police control, and as I had learned at an early day to speak Chinook (the "court language" among the coast tribes)

special work of keeping up the police control, and as I had learned at an early day to speak Chinook (the "court language" among the coast tribes) almost as well as the Indians themselves, I was thereby enabled to steer my way successfully on many critical occasions.

almost as well as the Indians themselves, I was thereby enabled to steer my way successfully on many critical occasions.

For some time the most disturbing and most troublesome element we had was the Rogue River band. For three or four years they had fought our troops obstinately,

band. For three or four years they had fought our troops obstinately, and surrendered at the bitter end in the belief that they were merely overpowered, not

and surrendered at the bitter end in the belief that they were merely overpowered, not  conquered. They openly boasted to the other Indians that they could whip the soldiers, and that they did not wish to follow the white man's ways, continuing consistently their wild habits, unmindful of all admonitions. Indeed, they often destroyed their household utensils, tepees and clothing, and killed their horses on the graves of the dead,

conquered. They openly boasted to the other Indians that they could whip the soldiers, and that they did not wish to follow the white man's ways, continuing consistently their wild habits, unmindful of all admonitions. Indeed, they often destroyed their household utensils, tepees and clothing, and killed their horses on the graves of the dead, in the fulfillment of a superstitious custom, which demanded that they should undergo, while mourning for their kindred, the deepest privation in a property sense. Everything the loss of which would make them poor was sacrificed on the graves of their

in the fulfillment of a superstitious custom, which demanded that they should undergo, while mourning for their kindred, the deepest privation in a property sense. Everything the loss of which would make them poor was sacrificed on the graves of their relatives or distinguished warriors, and as melancholy because of removal from their old homes caused frequent deaths, there was no lack of occasion for the sacrifices. The widows and orphans of the dead

relatives or distinguished warriors, and as melancholy because of removal from their old homes caused frequent deaths, there was no lack of occasion for the sacrifices. The widows and orphans of the dead  warriors were of course the chief mourners, and exhibited their grief in many peculiar ways. I

warriors were of course the chief mourners, and exhibited their grief in many peculiar ways. I  remember one in particular which was universally practiced by the near kinsfolk. They would crop their hair very close, and then cover the head with a sort of hood or plaster of black pitch, the composition being clay, pulverized charcoal, and the resinous gum which exudes from the pine-tree. The hood, nearly an inch in thickness, was worn during a period of mourning that lasted through the time it would take nature, by the growth of the hair, actually to lift from the head the heavy covering of pitch after it had become solidified and hard as stone. It must be admitted that they underwent considerable discomfort in memory of their relatives. It took all the influence we could bring to bear to break up these absurdly superstitious practices, and it looked as if no permanent improvement could be effected, for as soon as we got them to discard one, another would be invented. When not allowed to burn down their tepees or houses, those poor souls who were in a dying condition would be carried out to the neighboring hillsides just before dissolution, and there abandoned to their sufferings, with little or no attention, unless the placing under their heads of a small stick of wood—with possibly some laudable object, but doubtless great discomfort to their victim—might be considered such.

remember one in particular which was universally practiced by the near kinsfolk. They would crop their hair very close, and then cover the head with a sort of hood or plaster of black pitch, the composition being clay, pulverized charcoal, and the resinous gum which exudes from the pine-tree. The hood, nearly an inch in thickness, was worn during a period of mourning that lasted through the time it would take nature, by the growth of the hair, actually to lift from the head the heavy covering of pitch after it had become solidified and hard as stone. It must be admitted that they underwent considerable discomfort in memory of their relatives. It took all the influence we could bring to bear to break up these absurdly superstitious practices, and it looked as if no permanent improvement could be effected, for as soon as we got them to discard one, another would be invented. When not allowed to burn down their tepees or houses, those poor souls who were in a dying condition would be carried out to the neighboring hillsides just before dissolution, and there abandoned to their sufferings, with little or no attention, unless the placing under their heads of a small stick of wood—with possibly some laudable object, but doubtless great discomfort to their victim—might be considered such.

band. For three or four years they had fought our troops obstinately,

band. For three or four years they had fought our troops obstinately, and surrendered at the bitter end in the belief that they were merely overpowered, not

and surrendered at the bitter end in the belief that they were merely overpowered, not  conquered. They openly boasted to the other Indians that they could whip the soldiers, and that they did not wish to follow the white man's ways, continuing consistently their wild habits, unmindful of all admonitions. Indeed, they often destroyed their household utensils, tepees and clothing, and killed their horses on the graves of the dead,

conquered. They openly boasted to the other Indians that they could whip the soldiers, and that they did not wish to follow the white man's ways, continuing consistently their wild habits, unmindful of all admonitions. Indeed, they often destroyed their household utensils, tepees and clothing, and killed their horses on the graves of the dead, in the fulfillment of a superstitious custom, which demanded that they should undergo, while mourning for their kindred, the deepest privation in a property sense. Everything the loss of which would make them poor was sacrificed on the graves of their

in the fulfillment of a superstitious custom, which demanded that they should undergo, while mourning for their kindred, the deepest privation in a property sense. Everything the loss of which would make them poor was sacrificed on the graves of their relatives or distinguished warriors, and as melancholy because of removal from their old homes caused frequent deaths, there was no lack of occasion for the sacrifices. The widows and orphans of the dead

relatives or distinguished warriors, and as melancholy because of removal from their old homes caused frequent deaths, there was no lack of occasion for the sacrifices. The widows and orphans of the dead  warriors were of course the chief mourners, and exhibited their grief in many peculiar ways. I

warriors were of course the chief mourners, and exhibited their grief in many peculiar ways. I  remember one in particular which was universally practiced by the near kinsfolk. They would crop their hair very close, and then cover the head with a sort of hood or plaster of black pitch, the composition being clay, pulverized charcoal, and the resinous gum which exudes from the pine-tree. The hood, nearly an inch in thickness, was worn during a period of mourning that lasted through the time it would take nature, by the growth of the hair, actually to lift from the head the heavy covering of pitch after it had become solidified and hard as stone. It must be admitted that they underwent considerable discomfort in memory of their relatives. It took all the influence we could bring to bear to break up these absurdly superstitious practices, and it looked as if no permanent improvement could be effected, for as soon as we got them to discard one, another would be invented. When not allowed to burn down their tepees or houses, those poor souls who were in a dying condition would be carried out to the neighboring hillsides just before dissolution, and there abandoned to their sufferings, with little or no attention, unless the placing under their heads of a small stick of wood—with possibly some laudable object, but doubtless great discomfort to their victim—might be considered such.

remember one in particular which was universally practiced by the near kinsfolk. They would crop their hair very close, and then cover the head with a sort of hood or plaster of black pitch, the composition being clay, pulverized charcoal, and the resinous gum which exudes from the pine-tree. The hood, nearly an inch in thickness, was worn during a period of mourning that lasted through the time it would take nature, by the growth of the hair, actually to lift from the head the heavy covering of pitch after it had become solidified and hard as stone. It must be admitted that they underwent considerable discomfort in memory of their relatives. It took all the influence we could bring to bear to break up these absurdly superstitious practices, and it looked as if no permanent improvement could be effected, for as soon as we got them to discard one, another would be invented. When not allowed to burn down their tepees or houses, those poor souls who were in a dying condition would be carried out to the neighboring hillsides just before dissolution, and there abandoned to their sufferings, with little or no attention, unless the placing under their heads of a small stick of wood—with possibly some laudable object, but doubtless great discomfort to their victim—might be considered such.

No comments:

Post a Comment