The Pleasant Valley War, sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud, or Tonto Basin War, was commonly

The Pleasant Valley War, sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud, or Tonto Basin War, was commonly  thought to be an Arizona range war between two feuding families, the cattle-herding Grahams and the sheep-herding Tewksburys. However, eyewitness reports show that sheep were not brought into Pleasant Valley until 1885,

thought to be an Arizona range war between two feuding families, the cattle-herding Grahams and the sheep-herding Tewksburys. However, eyewitness reports show that sheep were not brought into Pleasant Valley until 1885, two years after the feuding between the Tewksbury and Graham factions began. Although Pleasant Valley is physically

two years after the feuding between the Tewksbury and Graham factions began. Although Pleasant Valley is physically  located in Gila County, Arizona, many of the events in the feud took place in Apache County,

located in Gila County, Arizona, many of the events in the feud took place in Apache County, and in Navajo County. The feud itself lasted for about a decade, with its most deadly incidents between 1886 and

and in Navajo County. The feud itself lasted for about a decade, with its most deadly incidents between 1886 and 1887, with the last known killing occurring in 1892. At one stage, outsider and known assassin Tom Horn

1887, with the last known killing occurring in 1892. At one stage, outsider and known assassin Tom Horn  participated as a killer for hire, but it is unknown as to which side employed him, and both sides suffered several murders to which no

participated as a killer for hire, but it is unknown as to which side employed him, and both sides suffered several murders to which no  suspect was ever identified. Of all the feuds that have taken place throughout American history, the Pleasant Valley War was the most costly, resulting in an almost complete annihilation of the two families involved.During the late 1880s, a number of range wars—informal undeclared violent conflicts—erupted between cattlemen and sheepmen over water rights, grazing rights, or property and border disagreements. In this case, there had been quarrels between the workhands of both factions as far back as 1882. The early clashes stemmed from accusations of cattle and horse rustling leveled at both parties, and some both the Tewksbury's and Grahams were arrested on charges made by another rancher,

suspect was ever identified. Of all the feuds that have taken place throughout American history, the Pleasant Valley War was the most costly, resulting in an almost complete annihilation of the two families involved.During the late 1880s, a number of range wars—informal undeclared violent conflicts—erupted between cattlemen and sheepmen over water rights, grazing rights, or property and border disagreements. In this case, there had been quarrels between the workhands of both factions as far back as 1882. The early clashes stemmed from accusations of cattle and horse rustling leveled at both parties, and some both the Tewksbury's and Grahams were arrested on charges made by another rancher,  Jim Stinson, that they all had taken part in rustling cattle from Stinson's ranch.

Jim Stinson, that they all had taken part in rustling cattle from Stinson's ranch.

There is also an undercurrent of racial prejudice against the Tewksburys who were half-Indian, and therefore referred to as "damn blacks" by the Grahams and Stinson. Stinson made a deal with the Grahams to pay them each fifty head of cattle and see that they never served jail time if they would turn state's evidence against the Tewksbury brothers. The Grahams took the deal and went to work for Stinson with the expressed vow to drive them out of Pleasant Valley. The case against the Tewksbury's was thrown out of court for lack of evidence.

The notion that this was a sheep v. cattle range war came about in part because the first killing in the feud was the murder of a Basque sheep herder who worked for the Daggs Brothers sheep ranch in northern Arizona. In 1885, the Tewksbury brothers leased some sheep from Daggs, and they sent the sheep to Pleasant Valley with the Basque sheep herder. The Basque sheep herder was murdered and robbed by Andy Cooper who was one of

In 1885, the Tewksbury brothers leased some sheep from Daggs, and they sent the sheep to Pleasant Valley with the Basque sheep herder. The Basque sheep herder was murdered and robbed by Andy Cooper who was one of the Graham faction. Overall, between twenty to thirty-four deaths resulted directly from the feud.

the Graham faction. Overall, between twenty to thirty-four deaths resulted directly from the feud.

In 1885, the Tewksbury brothers leased some sheep from Daggs, and they sent the sheep to Pleasant Valley with the Basque sheep herder. The Basque sheep herder was murdered and robbed by Andy Cooper who was one of

In 1885, the Tewksbury brothers leased some sheep from Daggs, and they sent the sheep to Pleasant Valley with the Basque sheep herder. The Basque sheep herder was murdered and robbed by Andy Cooper who was one of the Graham faction. Overall, between twenty to thirty-four deaths resulted directly from the feud.

the Graham faction. Overall, between twenty to thirty-four deaths resulted directly from the feud.

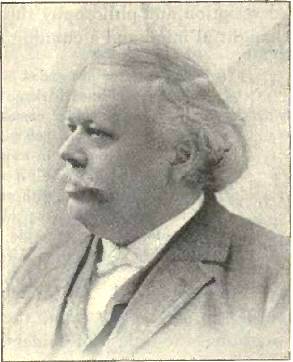

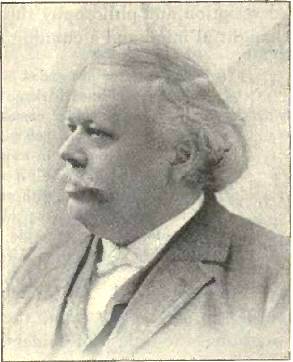

Once partisan feelings became tense and hostilities began, Frederick Russell Burnham was drawn into the conflict in 1884. Initially he was not involved but was dragged into it and subsequently marked for death. Burnham hid for many days before he could escape from the valley. With the help of friends, he managed to get out of the feud district after several months during which he had a number of narrow escapes, accounts he recalls in his memoirs, Scouting on Two Continents.[A local cattleman, Fred Wells had borrowed a lot of money in Globe, Arizona

Initially he was not involved but was dragged into it and subsequently marked for death. Burnham hid for many days before he could escape from the valley. With the help of friends, he managed to get out of the feud district after several months during which he had a number of narrow escapes, accounts he recalls in his memoirs, Scouting on Two Continents.[A local cattleman, Fred Wells had borrowed a lot of money in Globe, Arizona  to build back his cattle herd. The Wells clan had no stake in the feud, but his creditors did. Wells was told to join their forces in driving off the opposition's cattle or forfeit his own stock. When Wells refused, his creditors demanded immediate payment of the loans and sent two deputies to attach his cattle.

to build back his cattle herd. The Wells clan had no stake in the feud, but his creditors did. Wells was told to join their forces in driving off the opposition's cattle or forfeit his own stock. When Wells refused, his creditors demanded immediate payment of the loans and sent two deputies to attach his cattle. Wells gathered his clan and cattle together along with a young ranch hand named Frederick Russell Burnham, below Edwin Tewkesbury and below that his grave

Wells gathered his clan and cattle together along with a young ranch hand named Frederick Russell Burnham, below Edwin Tewkesbury and below that his grave who Wells had trained in shooting and considered him almost a part of his family, and began driving his herd into the mountains, hotly pursued by the deputies.

who Wells had trained in shooting and considered him almost a part of his family, and began driving his herd into the mountains, hotly pursued by the deputies.

Initially he was not involved but was dragged into it and subsequently marked for death. Burnham hid for many days before he could escape from the valley. With the help of friends, he managed to get out of the feud district after several months during which he had a number of narrow escapes, accounts he recalls in his memoirs, Scouting on Two Continents.[A local cattleman, Fred Wells had borrowed a lot of money in Globe, Arizona

Initially he was not involved but was dragged into it and subsequently marked for death. Burnham hid for many days before he could escape from the valley. With the help of friends, he managed to get out of the feud district after several months during which he had a number of narrow escapes, accounts he recalls in his memoirs, Scouting on Two Continents.[A local cattleman, Fred Wells had borrowed a lot of money in Globe, Arizona  Wells gathered his clan and cattle together along with a young ranch hand named Frederick Russell Burnham, below Edwin Tewkesbury and below that his grave

Wells gathered his clan and cattle together along with a young ranch hand named Frederick Russell Burnham, below Edwin Tewkesbury and below that his grave who Wells had trained in shooting and considered him almost a part of his family, and began driving his herd into the mountains, hotly pursued by the deputies.

who Wells had trained in shooting and considered him almost a part of his family, and began driving his herd into the mountains, hotly pursued by the deputies.

It was slow going to drive the cattle into the mountains and the deputies had no trouble overtaking the Wells clan. The deputies forced the girls and the mother to halt which then set off the barking dogs. Burnham and John Wells, the son of Fred Wells and Burnham's close friend, rushed back. Just when they arrived one of the dogs bit a deputy as he was dismounting. The deputy drew and shot the dog, which then caused Burnham, John, and two of the girls to also draw their weapons. The dismounted deputy then fell dead, shot from a long distance by Fred Wells, and the other deputy raised his hands. The clan continued into the mountains with the captured deputy and then released him once their objectives were secure. The deputy returned to Globe and reported on the incident.

In Globe, a meeting was held to discuss the elimination of Fred and John Wells, and an "unknown gunman carrying a Remington six-shoot belt", that is, Burnham and his Remington Model 1875 sidearm  and bandolier. Private posses were raised for raiding the opposition. Killings and counter-killings became a weekly occurrence. For the Wells outfit it became a sheer waste of human life in a struggle without honor or profit in another mans feud, and seemingly without end.For Burnham, it became apparent that he had the worst of two worlds.

and bandolier. Private posses were raised for raiding the opposition. Killings and counter-killings became a weekly occurrence. For the Wells outfit it became a sheer waste of human life in a struggle without honor or profit in another mans feud, and seemingly without end.For Burnham, it became apparent that he had the worst of two worlds. His faction was losing and every man he killed created a new feud, a personal one, not winner take all, but winner take on all. Only nineteen years old and facing a grim future as a nameless gunslinger whose only "crime" had been to stand by his friends the Wells, Burnham went to Globe and looked up another friend, the editor of the

His faction was losing and every man he killed created a new feud, a personal one, not winner take all, but winner take on all. Only nineteen years old and facing a grim future as a nameless gunslinger whose only "crime" had been to stand by his friends the Wells, Burnham went to Globe and looked up another friend, the editor of the  Silver Belt newspaper. On his way to Globe he was nearly killed by George Dixon, a well-known bounty hunter and cattle rustler who found Burnham hiding in a cave. Dixon held a Colt 45 to Burnham's head and was orderng him outside when someone outside the cave shot and killed Dixon.

Silver Belt newspaper. On his way to Globe he was nearly killed by George Dixon, a well-known bounty hunter and cattle rustler who found Burnham hiding in a cave. Dixon held a Colt 45 to Burnham's head and was orderng him outside when someone outside the cave shot and killed Dixon. A White MountainApache nicknamed Coyotero had been tracking Dixon and he shot the bounty hunter through the heart just as he was capturing Burnham. Burnham immediately grabbed his Remington, moved behind a ledge, and shot Coyotero dead.

A White MountainApache nicknamed Coyotero had been tracking Dixon and he shot the bounty hunter through the heart just as he was capturing Burnham. Burnham immediately grabbed his Remington, moved behind a ledge, and shot Coyotero dead.

and bandolier. Private posses were raised for raiding the opposition. Killings and counter-killings became a weekly occurrence. For the Wells outfit it became a sheer waste of human life in a struggle without honor or profit in another mans feud, and seemingly without end.For Burnham, it became apparent that he had the worst of two worlds.

and bandolier. Private posses were raised for raiding the opposition. Killings and counter-killings became a weekly occurrence. For the Wells outfit it became a sheer waste of human life in a struggle without honor or profit in another mans feud, and seemingly without end.For Burnham, it became apparent that he had the worst of two worlds. His faction was losing and every man he killed created a new feud, a personal one, not winner take all, but winner take on all. Only nineteen years old and facing a grim future as a nameless gunslinger whose only "crime" had been to stand by his friends the Wells, Burnham went to Globe and looked up another friend, the editor of the

His faction was losing and every man he killed created a new feud, a personal one, not winner take all, but winner take on all. Only nineteen years old and facing a grim future as a nameless gunslinger whose only "crime" had been to stand by his friends the Wells, Burnham went to Globe and looked up another friend, the editor of the  Silver Belt newspaper. On his way to Globe he was nearly killed by George Dixon, a well-known bounty hunter and cattle rustler who found Burnham hiding in a cave. Dixon held a Colt 45 to Burnham's head and was orderng him outside when someone outside the cave shot and killed Dixon.

Silver Belt newspaper. On his way to Globe he was nearly killed by George Dixon, a well-known bounty hunter and cattle rustler who found Burnham hiding in a cave. Dixon held a Colt 45 to Burnham's head and was orderng him outside when someone outside the cave shot and killed Dixon. A White MountainApache nicknamed Coyotero had been tracking Dixon and he shot the bounty hunter through the heart just as he was capturing Burnham. Burnham immediately grabbed his Remington, moved behind a ledge, and shot Coyotero dead.

A White MountainApache nicknamed Coyotero had been tracking Dixon and he shot the bounty hunter through the heart just as he was capturing Burnham. Burnham immediately grabbed his Remington, moved behind a ledge, and shot Coyotero dead.

Once in Globe, Burnham contacted his friend, the Silver Belt editor, and stayed hidden in his house. With this man's help, Burnham assumed several aliases and made the difficult journey out of the Basin. He eventually arrived in Tombstone, Arizona, and stayed with friends of the Silver Belt editor. Once in Tombstone, he began to reflect on the feud: "Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder's cause [Ed note: John Wells] was all wrong; that avenging only led to more

Once in Tombstone, he began to reflect on the feud: "Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder's cause [Ed note: John Wells] was all wrong; that avenging only led to more  vengeance and to even greater injustice than that suffered through the often unjustly administered laws of the land. I realized that I was in the wrong and had been for a long time, without knowing it.

vengeance and to even greater injustice than that suffered through the often unjustly administered laws of the land. I realized that I was in the wrong and had been for a long time, without knowing it. That was why I had suffered so in the Pinal Mountains."

That was why I had suffered so in the Pinal Mountains." [3]n February, 1887 a Navajo employee of the Tewksburys was herding sheep in an area called the Mogollon Rim,

[3]n February, 1887 a Navajo employee of the Tewksburys was herding sheep in an area called the Mogollon Rim, which until that point had been tacitly accepted as the line across which sheep were not permitted. He was ambushed, shot and killed by Tom Graham, who buried him where he died.

which until that point had been tacitly accepted as the line across which sheep were not permitted. He was ambushed, shot and killed by Tom Graham, who buried him where he died.

Once in Tombstone, he began to reflect on the feud: "Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder's cause [Ed note: John Wells] was all wrong; that avenging only led to more

Once in Tombstone, he began to reflect on the feud: "Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder's cause [Ed note: John Wells] was all wrong; that avenging only led to more  That was why I had suffered so in the Pinal Mountains."

That was why I had suffered so in the Pinal Mountains." [3]n February, 1887 a Navajo employee of the Tewksburys was herding sheep in an area called the Mogollon Rim,

[3]n February, 1887 a Navajo employee of the Tewksburys was herding sheep in an area called the Mogollon Rim, which until that point had been tacitly accepted as the line across which sheep were not permitted. He was ambushed, shot and killed by Tom Graham, who buried him where he died.

which until that point had been tacitly accepted as the line across which sheep were not permitted. He was ambushed, shot and killed by Tom Graham, who buried him where he died.

In September, 1887, a grisly incident occurred which has been the basis of many stories about the feud and which sparked a deadly chain of events. The Graham faction surrounded a Tewksbury cabin in the early morning hours  and coolly shot down John Tewksbury and William Jacobs as they started out for horses.

and coolly shot down John Tewksbury and William Jacobs as they started out for horses.

and coolly shot down John Tewksbury and William Jacobs as they started out for horses.

and coolly shot down John Tewksbury and William Jacobs as they started out for horses.

The Grahams continued firing at the cabin for hours, with fire returned from within. As the battle continued, a drove of hogs began devouring the bodies of Tewksbury and Jacobs. Although the Grahams did not offer a truce, John  Tewksbury's wife came out of the cabin with a shovel. The firing stopped while she scooped out shallow graves for her husband and his companion. Firing on both sides resumed once she was back inside, but no further deaths occurred that day, and after a few hours the Grahams rode away.

Tewksbury's wife came out of the cabin with a shovel. The firing stopped while she scooped out shallow graves for her husband and his companion. Firing on both sides resumed once she was back inside, but no further deaths occurred that day, and after a few hours the Grahams rode away.

Tewksbury's wife came out of the cabin with a shovel. The firing stopped while she scooped out shallow graves for her husband and his companion. Firing on both sides resumed once she was back inside, but no further deaths occurred that day, and after a few hours the Grahams rode away.

Tewksbury's wife came out of the cabin with a shovel. The firing stopped while she scooped out shallow graves for her husband and his companion. Firing on both sides resumed once she was back inside, but no further deaths occurred that day, and after a few hours the Grahams rode away.

A few days later, Andy Cooper, or Andy Blevins, one of the leaders of the Graham faction, was overheard in a store in Holbrook, Arizona bragging that he had shot and killed both John Tewksbury and William Jacobs.

bragging that he had shot and killed both John Tewksbury and William Jacobs.  The sheriff for Apache County,

The sheriff for Apache County, Commodore Perry Owens, was a noted gunman, and had a warrant for Blevins' arrest on an unrelated charge.

Commodore Perry Owens, was a noted gunman, and had a warrant for Blevins' arrest on an unrelated charge. Owens rode alone out to the Blevins house near Holbrook to serve the warrant.

Owens rode alone out to the Blevins house near Holbrook to serve the warrant.

bragging that he had shot and killed both John Tewksbury and William Jacobs.

bragging that he had shot and killed both John Tewksbury and William Jacobs.  Commodore Perry Owens, was a noted gunman, and had a warrant for Blevins' arrest on an unrelated charge.

Commodore Perry Owens, was a noted gunman, and had a warrant for Blevins' arrest on an unrelated charge. Owens rode alone out to the Blevins house near Holbrook to serve the warrant.

Owens rode alone out to the Blevins house near Holbrook to serve the warrant. John Blevins, then came out the front door and fired a shot at Owens with a rifle. Owens returned fire, wounding John and killing Andy. A friend of the family named Mose Roberts who was in a back room, jumped up and through a window at the side of the house.

John Blevins, then came out the front door and fired a shot at Owens with a rifle. Owens returned fire, wounding John and killing Andy. A friend of the family named Mose Roberts who was in a back room, jumped up and through a window at the side of the house.

Owens, hearing the noise, ran to the side of the house and fired on the man, killing him. It is disputed as to whether Roberts was armed or not. Some reports indicate he was armed with a rifle, others alleged that he was unarmed. It has also been alleged that he only leaped through the window to avoid bullets that passed into his room. At that moment, fifteen year old Sam Houston Blevins then ran outside, armed with a pistol he had picked up off the floor next to the body of his brother Andy. With his mothers arms around him trying to hold him back, Owens shot and killed him, as the boy fired on Owens.

The whole incident took less than one minute but resulted in three dead and one wounded. Despite the shots fired at him, Owens was not injured. The afternoon made Owens a legend, but only added fuel to the fire of the feud. Owens was not indicted, and the shooting was ruled self defense without any trial. He was dismissed by the County Commission over the incident, mostly due to the boy being killed, regardless of the fact that the boy himself was armed.

In September 1887, Sheriff Mulvernon of Prescott, Arizona led a posse that pursued and killed John Graham and Charles Blevins during a shootout at Perkins Store in Young, Arizona.

Over the next few years after 1887, several lynchings and unsolved murders of members of both factions took  place, often committed by masked men. Both the Tewksburys and the Grahams continued fighting, until there were only two left.

place, often committed by masked men. Both the Tewksburys and the Grahams continued fighting, until there were only two left.

place, often committed by masked men. Both the Tewksburys and the Grahams continued fighting, until there were only two left.

place, often committed by masked men. Both the Tewksburys and the Grahams continued fighting, until there were only two left.

In 1892, Tom Graham, the last of the Graham faction involved in the feud, was murdered in Tempe, Arizona.  Edwin Tewksbury, the last of that faction involved in the feud, was accused of the murder. Defended by well-known Arizona attorney Thomas Fitch, the first trial ended in a mistrial due to a legal technicality.

Edwin Tewksbury, the last of that faction involved in the feud, was accused of the murder. Defended by well-known Arizona attorney Thomas Fitch, the first trial ended in a mistrial due to a legal technicality.

Edwin Tewksbury, the last of that faction involved in the feud, was accused of the murder. Defended by well-known Arizona attorney Thomas Fitch, the first trial ended in a mistrial due to a legal technicality.

Edwin Tewksbury, the last of that faction involved in the feud, was accused of the murder. Defended by well-known Arizona attorney Thomas Fitch, the first trial ended in a mistrial due to a legal technicality.

The jury in the second trial dead-locked seven to five for acquittal.[5] Edwin Tewksbury died in Globe, Arizona in April, 1904. By the time of his release, none of the Grahams remained to retaliate against him, nor was there anyone on the Tewksbury side to have avenged his death had anyone killed him.

The so-called sheep wars, conflicts between cattlemen and sheepmen over grazing rights, took place particularly between the early 1870s and 1900. Fundamental differences between sheep and cattle meant that they required different amounts of water, different types of food, and different manners of herding. Differences in life and equipment of the cowboy on horseback and the sheepherder on a burro or afoot also made for antagonisms. W,QumuBO(PMKkhzQ~~60_12.JPG) The cattleman had priority of establishment in most areas of Texas and resented encroachment of the sheepman on his domain. The cattleman was the more aggressive of the antagonists. His methods of attempting to drive out his rival

The cattleman had priority of establishment in most areas of Texas and resented encroachment of the sheepman on his domain. The cattleman was the more aggressive of the antagonists. His methods of attempting to drive out his rival ranged from intimidation to violence, directed at both the sheepman and his flock. Nomadic sheepmen or drifters were

ranged from intimidation to violence, directed at both the sheepman and his flock. Nomadic sheepmen or drifters were  attacked by both cattlemen and settled sheepmen because of their twisting or rolling of fences to allow passage of their flocks and because they drove sheep infected with scab across the ranges.

attacked by both cattlemen and settled sheepmen because of their twisting or rolling of fences to allow passage of their flocks and because they drove sheep infected with scab across the ranges. In 1875 there were clashes on the Charles Goodnight range and in the Texas-New Mexico boundary area. Schleicher, Nolan, Brown, Crane, Tom Green, Coleman, and other Central and West Texas counties were scenes of the

In 1875 there were clashes on the Charles Goodnight range and in the Texas-New Mexico boundary area. Schleicher, Nolan, Brown, Crane, Tom Green, Coleman, and other Central and West Texas counties were scenes of the wars.Charles Goodnight, rancher, the fourth of five children of Charles and Charlotte (Collier) Goodnight, was born on March 5, 1836, on the family farm in Macoupin County, Illinois. His father died of pneumonia in 1841 when Charles was five, and shortly

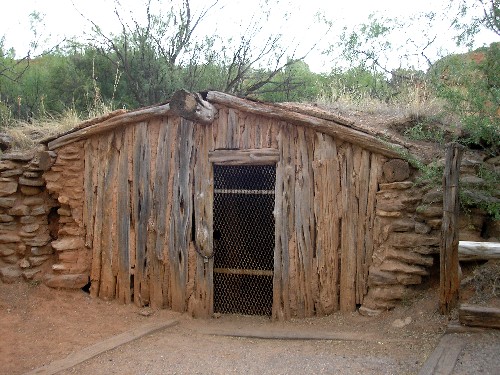

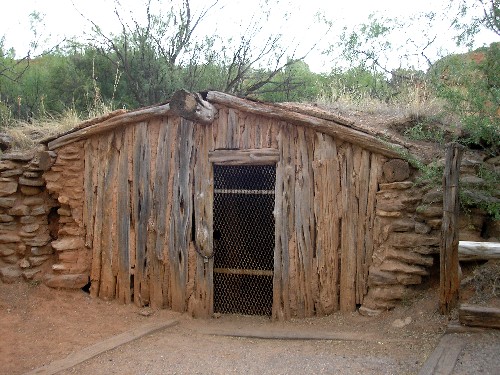

wars.Charles Goodnight, rancher, the fourth of five children of Charles and Charlotte (Collier) Goodnight, was born on March 5, 1836, on the family farm in Macoupin County, Illinois. His father died of pneumonia in 1841 when Charles was five, and shortly  thereafter his mother married Hiram Daugherty, a neighboring farmer. In all, Charles had only six months of formal schooling. Late in 1845 he accompanied his family on the 800-mile trek south to a site in Milam County, Texas

thereafter his mother married Hiram Daugherty, a neighboring farmer. In all, Charles had only six months of formal schooling. Late in 1845 he accompanied his family on the 800-mile trek south to a site in Milam County, Texas , near Nashville-on-the-Brazos, riding bareback on a white-faced mare named Blaze.

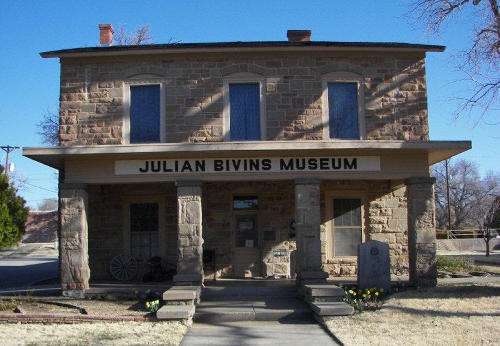

, near Nashville-on-the-Brazos, riding bareback on a white-faced mare named Blaze.  above goodnights home

above goodnights home

ranged from intimidation to violence, directed at both the sheepman and his flock. Nomadic sheepmen or drifters were

ranged from intimidation to violence, directed at both the sheepman and his flock. Nomadic sheepmen or drifters were  attacked by both cattlemen and settled sheepmen because of their twisting or rolling of fences to allow passage of their flocks and because they drove sheep infected with scab across the ranges.

attacked by both cattlemen and settled sheepmen because of their twisting or rolling of fences to allow passage of their flocks and because they drove sheep infected with scab across the ranges. In 1875 there were clashes on the Charles Goodnight range and in the Texas-New Mexico boundary area. Schleicher, Nolan, Brown, Crane, Tom Green, Coleman, and other Central and West Texas counties were scenes of the

In 1875 there were clashes on the Charles Goodnight range and in the Texas-New Mexico boundary area. Schleicher, Nolan, Brown, Crane, Tom Green, Coleman, and other Central and West Texas counties were scenes of the wars.Charles Goodnight, rancher, the fourth of five children of Charles and Charlotte (Collier) Goodnight, was born on March 5, 1836, on the family farm in Macoupin County, Illinois. His father died of pneumonia in 1841 when Charles was five, and shortly

wars.Charles Goodnight, rancher, the fourth of five children of Charles and Charlotte (Collier) Goodnight, was born on March 5, 1836, on the family farm in Macoupin County, Illinois. His father died of pneumonia in 1841 when Charles was five, and shortly  thereafter his mother married Hiram Daugherty, a neighboring farmer. In all, Charles had only six months of formal schooling. Late in 1845 he accompanied his family on the 800-mile trek south to a site in Milam County, Texas

thereafter his mother married Hiram Daugherty, a neighboring farmer. In all, Charles had only six months of formal schooling. Late in 1845 he accompanied his family on the 800-mile trek south to a site in Milam County, Texas , near Nashville-on-the-Brazos, riding bareback on a white-faced mare named Blaze.

, near Nashville-on-the-Brazos, riding bareback on a white-faced mare named Blaze.  above goodnights home

above goodnights home

He later took pride in the fact that he was born at the same time as the Republic of Texas and that he "joined" Texas the year it joined the Union. Growing up in the Brazos bottoms, the boy learned to hunt and track from an old Indian named Caddo Jake. At age eleven Charles began hiring out to neighboring farms, and at fifteen he rode as a jockey for a racing outfit at Port Sullivan. Not satisfied

Growing up in the Brazos bottoms, the boy learned to hunt and track from an old Indian named Caddo Jake. At age eleven Charles began hiring out to neighboring farms, and at fifteen he rode as a jockey for a racing outfit at Port Sullivan. Not satisfied  with that occupation, he returned to his widowed mother and younger siblings, continued at various farm and plantation jobs, including supervision of black slave crews,

with that occupation, he returned to his widowed mother and younger siblings, continued at various farm and plantation jobs, including supervision of black slave crews,  and for two years freighted with ox teams. In 1853 his mother married Rev. Adam Sheek, a Methodist preacher; that led to the formation of the partnership three years later between Charles and his step-brother, John Wesley Sheek. Although they considered going to California, they were dissuaded by Sheek's brother-in-law, Claiborne Varner, who induced them to run about 400 head of cattle on shares along the Brazos valley for a ten-year period. In 1857 the young partners trailed their herd up the Brazos to the Keechi valley in Palo Pinto County. At Black Springs they built a log cabin buttressed with stone chimneys, to which they brought their parents in 1858. Goodnight continued freighting cotton and provisions to Houston and back for a time until Wes Sheek married, then assumed the bulk of responsibility of looking after the growing herd of scrawny, wild Texas cattle. With his acquired hunting and trailing skills, he quickly mastered the modes of survival in the wilderness. During this time he became acquainted with Oliver Loving,

and for two years freighted with ox teams. In 1853 his mother married Rev. Adam Sheek, a Methodist preacher; that led to the formation of the partnership three years later between Charles and his step-brother, John Wesley Sheek. Although they considered going to California, they were dissuaded by Sheek's brother-in-law, Claiborne Varner, who induced them to run about 400 head of cattle on shares along the Brazos valley for a ten-year period. In 1857 the young partners trailed their herd up the Brazos to the Keechi valley in Palo Pinto County. At Black Springs they built a log cabin buttressed with stone chimneys, to which they brought their parents in 1858. Goodnight continued freighting cotton and provisions to Houston and back for a time until Wes Sheek married, then assumed the bulk of responsibility of looking after the growing herd of scrawny, wild Texas cattle. With his acquired hunting and trailing skills, he quickly mastered the modes of survival in the wilderness. During this time he became acquainted with Oliver Loving, who was also running cattle in the Western Cross Timbers. When the gold rush to Colorado began, Goodnight helped Loving send a herd through the Indian Territory and Kansas to the Rocky Mountain mining camps.

who was also running cattle in the Western Cross Timbers. When the gold rush to Colorado began, Goodnight helped Loving send a herd through the Indian Territory and Kansas to the Rocky Mountain mining camps. A law of March 9, 1881, which provided for appointment of state sheep inspectors and the quarantine of diseased sheep, merely resulted in driving drifters under cover. Laws that forbade sheepmen to herd sheep on the open range were ineffective because no representatives of the General Land Office were located in West Texas to delimit the open range.

A law of March 9, 1881, which provided for appointment of state sheep inspectors and the quarantine of diseased sheep, merely resulted in driving drifters under cover. Laws that forbade sheepmen to herd sheep on the open range were ineffective because no representatives of the General Land Office were located in West Texas to delimit the open range. A law of April 1883 called for a certificate of inspection to show that sheep were free of scab before they could be moved across a county line. Legislation, along with strict enforcement of tax collections, soon put a stop to nomadic sheepherders from out of state using Texas lands. With the general rush for leasing public lands after 1884, many

A law of April 1883 called for a certificate of inspection to show that sheep were free of scab before they could be moved across a county line. Legislation, along with strict enforcement of tax collections, soon put a stop to nomadic sheepherders from out of state using Texas lands. With the general rush for leasing public lands after 1884, many  sheepmen could not secure adjoining pastures and had to drive their herds across ranchers' lands, the sheep grazing on the pastures as they crossed. A code was evolved that required the herder to drive his flocks at least five miles a day on level terrain or at least three miles a day in rougher country. In court action, the cowman usually won. After the law of

sheepmen could not secure adjoining pastures and had to drive their herds across ranchers' lands, the sheep grazing on the pastures as they crossed. A code was evolved that required the herder to drive his flocks at least five miles a day on level terrain or at least three miles a day in rougher country. In court action, the cowman usually won. After the law of  1884, which made fence-cutting a felony and abolished the open range, both the cattleman and the sheepman confined their herds to their own land, and the sheep wars came to an end. Despite the occasional fights between sheepherders and cattlemen in Texas, the level of violence never reached that of some other Western states. Moreover, sheepherders and cattlemen in many areas lived in peaceful coexistence, and some ranchers ran sheep, cattle, and goats on their

1884, which made fence-cutting a felony and abolished the open range, both the cattleman and the sheepman confined their herds to their own land, and the sheep wars came to an end. Despite the occasional fights between sheepherders and cattlemen in Texas, the level of violence never reached that of some other Western states. Moreover, sheepherders and cattlemen in many areas lived in peaceful coexistence, and some ranchers ran sheep, cattle, and goats on their  spreads.

spreads.

Growing up in the Brazos bottoms, the boy learned to hunt and track from an old Indian named Caddo Jake. At age eleven Charles began hiring out to neighboring farms, and at fifteen he rode as a jockey for a racing outfit at Port Sullivan. Not satisfied

Growing up in the Brazos bottoms, the boy learned to hunt and track from an old Indian named Caddo Jake. At age eleven Charles began hiring out to neighboring farms, and at fifteen he rode as a jockey for a racing outfit at Port Sullivan. Not satisfied  with that occupation, he returned to his widowed mother and younger siblings, continued at various farm and plantation jobs, including supervision of black slave crews,

with that occupation, he returned to his widowed mother and younger siblings, continued at various farm and plantation jobs, including supervision of black slave crews,  and for two years freighted with ox teams. In 1853 his mother married Rev. Adam Sheek, a Methodist preacher; that led to the formation of the partnership three years later between Charles and his step-brother, John Wesley Sheek. Although they considered going to California, they were dissuaded by Sheek's brother-in-law, Claiborne Varner, who induced them to run about 400 head of cattle on shares along the Brazos valley for a ten-year period. In 1857 the young partners trailed their herd up the Brazos to the Keechi valley in Palo Pinto County. At Black Springs they built a log cabin buttressed with stone chimneys, to which they brought their parents in 1858. Goodnight continued freighting cotton and provisions to Houston and back for a time until Wes Sheek married, then assumed the bulk of responsibility of looking after the growing herd of scrawny, wild Texas cattle. With his acquired hunting and trailing skills, he quickly mastered the modes of survival in the wilderness. During this time he became acquainted with Oliver Loving,

and for two years freighted with ox teams. In 1853 his mother married Rev. Adam Sheek, a Methodist preacher; that led to the formation of the partnership three years later between Charles and his step-brother, John Wesley Sheek. Although they considered going to California, they were dissuaded by Sheek's brother-in-law, Claiborne Varner, who induced them to run about 400 head of cattle on shares along the Brazos valley for a ten-year period. In 1857 the young partners trailed their herd up the Brazos to the Keechi valley in Palo Pinto County. At Black Springs they built a log cabin buttressed with stone chimneys, to which they brought their parents in 1858. Goodnight continued freighting cotton and provisions to Houston and back for a time until Wes Sheek married, then assumed the bulk of responsibility of looking after the growing herd of scrawny, wild Texas cattle. With his acquired hunting and trailing skills, he quickly mastered the modes of survival in the wilderness. During this time he became acquainted with Oliver Loving, who was also running cattle in the Western Cross Timbers. When the gold rush to Colorado began, Goodnight helped Loving send a herd through the Indian Territory and Kansas to the Rocky Mountain mining camps.

who was also running cattle in the Western Cross Timbers. When the gold rush to Colorado began, Goodnight helped Loving send a herd through the Indian Territory and Kansas to the Rocky Mountain mining camps. A law of March 9, 1881, which provided for appointment of state sheep inspectors and the quarantine of diseased sheep, merely resulted in driving drifters under cover. Laws that forbade sheepmen to herd sheep on the open range were ineffective because no representatives of the General Land Office were located in West Texas to delimit the open range.

A law of March 9, 1881, which provided for appointment of state sheep inspectors and the quarantine of diseased sheep, merely resulted in driving drifters under cover. Laws that forbade sheepmen to herd sheep on the open range were ineffective because no representatives of the General Land Office were located in West Texas to delimit the open range. A law of April 1883 called for a certificate of inspection to show that sheep were free of scab before they could be moved across a county line. Legislation, along with strict enforcement of tax collections, soon put a stop to nomadic sheepherders from out of state using Texas lands. With the general rush for leasing public lands after 1884, many

A law of April 1883 called for a certificate of inspection to show that sheep were free of scab before they could be moved across a county line. Legislation, along with strict enforcement of tax collections, soon put a stop to nomadic sheepherders from out of state using Texas lands. With the general rush for leasing public lands after 1884, many  sheepmen could not secure adjoining pastures and had to drive their herds across ranchers' lands, the sheep grazing on the pastures as they crossed. A code was evolved that required the herder to drive his flocks at least five miles a day on level terrain or at least three miles a day in rougher country. In court action, the cowman usually won. After the law of

sheepmen could not secure adjoining pastures and had to drive their herds across ranchers' lands, the sheep grazing on the pastures as they crossed. A code was evolved that required the herder to drive his flocks at least five miles a day on level terrain or at least three miles a day in rougher country. In court action, the cowman usually won. After the law of  1884, which made fence-cutting a felony and abolished the open range, both the cattleman and the sheepman confined their herds to their own land, and the sheep wars came to an end. Despite the occasional fights between sheepherders and cattlemen in Texas, the level of violence never reached that of some other Western states. Moreover, sheepherders and cattlemen in many areas lived in peaceful coexistence, and some ranchers ran sheep, cattle, and goats on their

1884, which made fence-cutting a felony and abolished the open range, both the cattleman and the sheepman confined their herds to their own land, and the sheep wars came to an end. Despite the occasional fights between sheepherders and cattlemen in Texas, the level of violence never reached that of some other Western states. Moreover, sheepherders and cattlemen in many areas lived in peaceful coexistence, and some ranchers ran sheep, cattle, and goats on their  spreads.

spreads.

The pastores were sheepmen, usually of Hispanic origin from New Mexico, who settled with their flocks along the Canadian River and its tributaries during the 1870s and early 1880s. Although they stayed only for a brief period, they made a significant impact on both the society and agriculture of the Texas Panhandle. Since numerous flocks of sheep had practically overrun available ranges in New Mexico by 1874

,

, the pastores began looking toward the Llano Estacado with its lush river valleys and seemingly endless grasslands. Even prior to 1874 a few daring Indian and Mexican sheepmen probably herded their flocks on a seasonal basis along the upper Canadian as far east as the area of present Oldham County.

the pastores began looking toward the Llano Estacado with its lush river valleys and seemingly endless grasslands. Even prior to 1874 a few daring Indian and Mexican sheepmen probably herded their flocks on a seasonal basis along the upper Canadian as far east as the area of present Oldham County. Sometimes they utilized the old cibolero and Comancherocampsites on which they erected crude rock shelters.

Sometimes they utilized the old cibolero and Comancherocampsites on which they erected crude rock shelters. In their search for the best grass and water itinerant pastores are thought to have made large circuits and followed old Indian trade routes as far east as Palo Duro Canyon or beyond on occasion. Often several large flocks would travel

In their search for the best grass and water itinerant pastores are thought to have made large circuits and followed old Indian trade routes as far east as Palo Duro Canyon or beyond on occasion. Often several large flocks would travel  simultaneously over the circuit under the watchful eye of a mayordomo, who, with the aid of well-trained sheep dogs,

simultaneously over the circuit under the watchful eye of a mayordomo, who, with the aid of well-trained sheep dogs,  directed the movement of the sheep as he rode from one flock to another. Although poorly armed and thus easy targets for nomadic warriors, the pastores usually enjoyed fairly peaceful relations with the Plains tribes. Even so, they stayed wary of any Indians who might have resented their intrusion. During the 1860s a small group of families from New Mexico established a settlement on the Canadian

directed the movement of the sheep as he rode from one flock to another. Although poorly armed and thus easy targets for nomadic warriors, the pastores usually enjoyed fairly peaceful relations with the Plains tribes. Even so, they stayed wary of any Indians who might have resented their intrusion. During the 1860s a small group of families from New Mexico established a settlement on the Canadian  below Parker Creek at a site now in Oldham County, but they only stayed briefly.

below Parker Creek at a site now in Oldham County, but they only stayed briefly.  Soon after the Civil War a sheepman named Antonio Baca reportedly ran 30,000 head in the area of the present Oklahoma Panhandle, but because of the potential Indian danger these transientpastores never remained for long. After the Red River War,

Soon after the Civil War a sheepman named Antonio Baca reportedly ran 30,000 head in the area of the present Oklahoma Panhandle, but because of the potential Indian danger these transientpastores never remained for long. After the Red River War,

,

, the pastores began looking toward the Llano Estacado with its lush river valleys and seemingly endless grasslands. Even prior to 1874 a few daring Indian and Mexican sheepmen probably herded their flocks on a seasonal basis along the upper Canadian as far east as the area of present Oldham County.

the pastores began looking toward the Llano Estacado with its lush river valleys and seemingly endless grasslands. Even prior to 1874 a few daring Indian and Mexican sheepmen probably herded their flocks on a seasonal basis along the upper Canadian as far east as the area of present Oldham County. Sometimes they utilized the old cibolero and Comancherocampsites on which they erected crude rock shelters.

Sometimes they utilized the old cibolero and Comancherocampsites on which they erected crude rock shelters. In their search for the best grass and water itinerant pastores are thought to have made large circuits and followed old Indian trade routes as far east as Palo Duro Canyon or beyond on occasion. Often several large flocks would travel

In their search for the best grass and water itinerant pastores are thought to have made large circuits and followed old Indian trade routes as far east as Palo Duro Canyon or beyond on occasion. Often several large flocks would travel  simultaneously over the circuit under the watchful eye of a mayordomo, who, with the aid of well-trained sheep dogs,

simultaneously over the circuit under the watchful eye of a mayordomo, who, with the aid of well-trained sheep dogs,  directed the movement of the sheep as he rode from one flock to another. Although poorly armed and thus easy targets for nomadic warriors, the pastores usually enjoyed fairly peaceful relations with the Plains tribes. Even so, they stayed wary of any Indians who might have resented their intrusion. During the 1860s a small group of families from New Mexico established a settlement on the Canadian

directed the movement of the sheep as he rode from one flock to another. Although poorly armed and thus easy targets for nomadic warriors, the pastores usually enjoyed fairly peaceful relations with the Plains tribes. Even so, they stayed wary of any Indians who might have resented their intrusion. During the 1860s a small group of families from New Mexico established a settlement on the Canadian  below Parker Creek at a site now in Oldham County, but they only stayed briefly.

below Parker Creek at a site now in Oldham County, but they only stayed briefly.  Soon after the Civil War a sheepman named Antonio Baca reportedly ran 30,000 head in the area of the present Oklahoma Panhandle, but because of the potential Indian danger these transientpastores never remained for long. After the Red River War,

Soon after the Civil War a sheepman named Antonio Baca reportedly ran 30,000 head in the area of the present Oklahoma Panhandle, but because of the potential Indian danger these transientpastores never remained for long. After the Red River War,

when the nomadic Indians were confined to their reservationsThe Red River War, a series of military engagements fought between the United States Army and warriors of the Kiowa, Comanche, Southern Cheyenne, and southern  Arapaho Indian tribes from June of 1874 into the spring of 1875, began when the federal government defaulted on obligations undertaken to those tribes by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867. Rations to be issued the Indians

Arapaho Indian tribes from June of 1874 into the spring of 1875, began when the federal government defaulted on obligations undertaken to those tribes by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867. Rations to be issued the Indians  consistently fell short or failed entirely, gun running and liquor trafficking by white profiteers were not curtailed, and white outlaws from both Kansas and Texas who entered the Indian Territory to steal Indian stock were not punished or even, in most cases, pursued. On all these counts, the two federal Indian agents who dealt with the Indians, James M. Haworth at Fort Sill and John D. Miles at Darlington, both Quaker missionaries, did everything in their power to remedy the situation, but they received no cooperation from either the military or the Washington officials of the Office of Indian Affairs.,

consistently fell short or failed entirely, gun running and liquor trafficking by white profiteers were not curtailed, and white outlaws from both Kansas and Texas who entered the Indian Territory to steal Indian stock were not punished or even, in most cases, pursued. On all these counts, the two federal Indian agents who dealt with the Indians, James M. Haworth at Fort Sill and John D. Miles at Darlington, both Quaker missionaries, did everything in their power to remedy the situation, but they received no cooperation from either the military or the Washington officials of the Office of Indian Affairs.,

Arapaho Indian tribes from June of 1874 into the spring of 1875, began when the federal government defaulted on obligations undertaken to those tribes by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867. Rations to be issued the Indians

Arapaho Indian tribes from June of 1874 into the spring of 1875, began when the federal government defaulted on obligations undertaken to those tribes by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867. Rations to be issued the Indians  consistently fell short or failed entirely, gun running and liquor trafficking by white profiteers were not curtailed, and white outlaws from both Kansas and Texas who entered the Indian Territory to steal Indian stock were not punished or even, in most cases, pursued. On all these counts, the two federal Indian agents who dealt with the Indians, James M. Haworth at Fort Sill and John D. Miles at Darlington, both Quaker missionaries, did everything in their power to remedy the situation, but they received no cooperation from either the military or the Washington officials of the Office of Indian Affairs.,

consistently fell short or failed entirely, gun running and liquor trafficking by white profiteers were not curtailed, and white outlaws from both Kansas and Texas who entered the Indian Territory to steal Indian stock were not punished or even, in most cases, pursued. On all these counts, the two federal Indian agents who dealt with the Indians, James M. Haworth at Fort Sill and John D. Miles at Darlington, both Quaker missionaries, did everything in their power to remedy the situation, but they received no cooperation from either the military or the Washington officials of the Office of Indian Affairs.,

pastores began infiltrating the Panhandle more frequently. Some of them carried on trade with hunting parties of Indians who, with permits from the federal government agents, sought out the few remaining buffalo in the area.

more frequently. Some of them carried on trade with hunting parties of Indians who, with permits from the federal government agents, sought out the few remaining buffalo in the area.

more frequently. Some of them carried on trade with hunting parties of Indians who, with permits from the federal government agents, sought out the few remaining buffalo in the area.

more frequently. Some of them carried on trade with hunting parties of Indians who, with permits from the federal government agents, sought out the few remaining buffalo in the area.

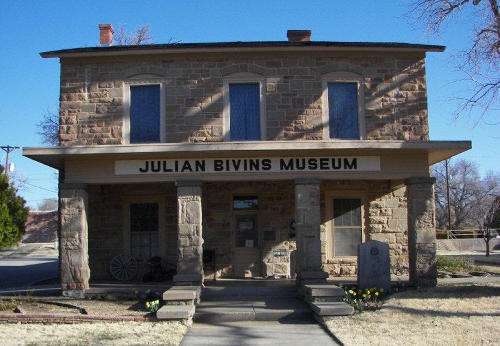

The pastores exchanged cattle and trade goods from Las Vegas and other New Mexico towns for horses )ZBRDnFNQ(5!~~60_12.JPG) and whatever items the Indians had to offer. This trade gradually diminished as hide hunters exterminated the once-numerous buffalo herds.

and whatever items the Indians had to offer. This trade gradually diminished as hide hunters exterminated the once-numerous buffalo herds.

)ZBRDnFNQ(5!~~60_12.JPG) and whatever items the Indians had to offer. This trade gradually diminished as hide hunters exterminated the once-numerous buffalo herds.

and whatever items the Indians had to offer. This trade gradually diminished as hide hunters exterminated the once-numerous buffalo herds.

No comments:

Post a Comment