berliner

berlinerposse would never be prosecuted because of arrangements with Arizona authorities.

He most likely would have been right had a two-bit con man named Perry Mallon not “arrested” him on a trumped up charge in Denver.

The arrest gave local officials in Arizona who were not parties to the arrangement an opportunity to demand extradition of Doc to Arizona to face murder charges.

Mallon’s unexpected inter-vention forced Arizona Gov. Frederick Tritle to pursue a matter he would just as lief leave alone. Even before the governor could begin the process of preparing the requisite

By the time that the extradition was denied, Doc’s story had gained a national audience. His arrest for larceny in Pueblo even introduced a new word to Colorado’s legal lexicon—“Hollidaying,” which

referred to the practice of filing false charges against an individual to avoid the prosecution of real ones.

referred to the practice of filing false charges against an individual to avoid the prosecution of real ones.

The extradition controversy marked the beginning of a new—and final—chapter in Doc’s life. He had previously qualified as a “well-known sport” who had been in and out of trouble in Texas, Kansas,

New Mexico and Arizona. He earned a reputation as a bad man in Arizona, but he gained a national reputation from his Colorado days. Newspaper editors from Denver to Kansas City to Cincinnati filled columns with stories about Doc that made Jesse James and Billy the Kid “fade into insignificance.”

New Mexico and Arizona. He earned a reputation as a bad man in Arizona, but he gained a national reputation from his Colorado days. Newspaper editors from Denver to Kansas City to Cincinnati filled columns with stories about Doc that made Jesse James and Billy the Kid “fade into insignificance.”No one cared that the controversy was all “twaddle,” as one Colorado editor put it. It gained a life of its own, and it produced an additional stream of stories designed to set the record straight from both friends and enemies of Doc’s.

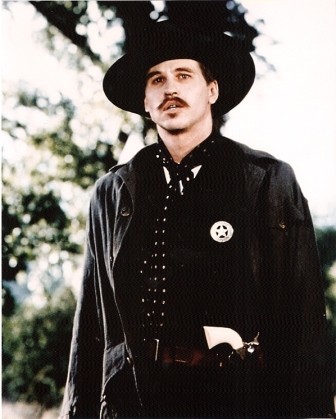

These stories did not stand up well against the facts, but they did provide at least a bare outline of Doc’s life, from his birth until his departure from Tombstone, Arizona. They also gave him the image of a dapper, quiet-spoken, gentlemanly man, even while they fed his image as a deadly mankiller.

These stories did not stand up well against the facts, but they did provide at least a bare outline of Doc’s life, from his birth until his departure from Tombstone, Arizona. They also gave him the image of a dapper, quiet-spoken, gentlemanly man, even while they fed his image as a deadly mankiller. the earps and doc

the earps and docDoc himself told his side of the story with a soft Southern drawl and a genteel demeanor that surprised reporters, especially in light of Mallon’s wild tales. He became an enigma, endlessly interesting because of the seeming contrast between his personality and the claims about his murderous record. Doc assured a reporter in Gunnison,

who was clearly charmed by him, “I’m not traveling about the country in search of notoriety, and I think you newspaper fellows have already had a fair hack at me.”

who was clearly charmed by him, “I’m not traveling about the country in search of notoriety, and I think you newspaper fellows have already had a fair hack at me.”

If the gunfighter-dentist believed his appeal to the public would change, he was mistaken. For the rest of his life, notoriety defined him and affected how others responded to him. It opened doors and closed them, inspiring awe and ridicule. In an odd way, his reputation even seemed to protect him. He was involved in only one deadly encounter from the time he arrived in Colorado until his death.

The extradition may have contributed to his good behavior in another way. After Gov. Pitkin refused to honor the extradition, Denver’s Rocky Mountain News reported that, “He feels perfectly safe against any and all proceedings that may be brought against him in the neighboring territory of Arizona, being protected by Colorado state authorities.”

But an old friend from Georgia told reporters in Atlanta that Doc would have returned home to Georgia “were it not for the fear that he would be turned over to the authorities of Arizona and Tombstone.”

In 1884, during his troubles in Leadville, Doc told a reporter, “If I should kill someone here...no matter if I were acquitted, the governor would be sure to turn me over to the Arizona authorities, and I would stand no show for life there at all.”

What was he basing such fear upon? Arizona made no more attempts to arrest any of the members of the Earp posse after the failure to extradite Doc in 1882. Wyatt Earp, his brother Warren and the other vendetta riders moved about at will, while Doc, for a time at least, seemed confined to Colorado. Was there some secret caveat that he would be safe in Colorado so long as he stayed out of trouble? Or might it have been something as simple as Doc’s own desire to stay in Colorado and being fearful he could not if he stepped out of line?

Once released in Pueblo on bond, he went to Gunnison for a brief reunion with the Earps. He later visited a few other camps and traveled back to Pueblo to keep a court date. On July 18, 1882, Doc was reportedly “visiting Leadville.”

Leadville had graduated from boom camp to city—lively, urbane, wealthy and wide open. With 120 saloons, 118 gambling halls, 110 beer gardens and 35 brothels, it was a “field of dreams” for a sporting man like Doc.

Leadville had graduated from boom camp to city—lively, urbane, wealthy and wide open. With 120 saloons, 118 gambling halls, 110 beer gardens and 35 brothels, it was a “field of dreams” for a sporting man like Doc.

His notoriety opened doors for him in the best of saloons and gambling houses. He was a celebrity. Men bought him drinks and invited him to join high roller games.

He found old friends there and made new ones. He ran into old enemies as well, although he managed to avoid trouble with them for a while. He registered to vote. He became a charter member of the Lake County Independent Club, which reflected his interest in Colorado state politics. He was acknowledged in the newspaper for his role in fighting a major fire. He attended social events, was a regular at horse races and boxing contests, and hobnobbed with the mining elite who frequented the upscale gambling houses and variety theatres.

He found old friends there and made new ones. He ran into old enemies as well, although he managed to avoid trouble with them for a while. He registered to vote. He became a charter member of the Lake County Independent Club, which reflected his interest in Colorado state politics. He was acknowledged in the newspaper for his role in fighting a major fire. He attended social events, was a regular at horse races and boxing contests, and hobnobbed with the mining elite who frequented the upscale gambling houses and variety theatres.The only blemish on his record in 1882 came three days before Christmas, when he was arrested for being drunk and carrying a concealed weapon. After that, however, he managed to stay out of trouble. Even his failure to appear in court in Pueblo in April 1883 was prearranged. His sureties forfeited bond, and the case was closed, just as its designers had intended.

Doc flourished in Leadville. That spring of 1883, a city correspondent described him dealing cards in the Marble Hall Saloon and Gambling House: “He is a thin, spare looking man; his iron gray hair is always well combed and oiled; his boots usually wear an immaculate polish; his beautiful scarf, with an elegant diamond pin in the center, looks well on his glossy shirt front, and he prides himself on always being scrupulously neat and clean. He usually talks in a very low tone.... In his pocket he always carries a beautiful, silver-mounted revolver, 45 caliber, and while talking to a stranger, his right arm restlessly wanders in that vicinity.” The Doc mystique was now clearly fixed. He was “one of the quietest and most gentlemanly men I’ve ever met,” the reporter continued, despite having killed “only fourteen men.”

In May 1883, Doc joined Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp in Silverton

Whether or not Doc was actually one of the invaders in the “Dodge City War,” the pro-Short forces made good use of his reputation.

Doc was soon back in Leadville, dealing cards at Cy Allen’s Monarch Saloon, but life for him soon took a turn for the worse. In October, he learned that his first cousin, Martha Anne Holliday, his dear “Mattie,” the family member who he cherished most, had entered the religious order of the Sisters of Mercy in Savannah, Georgia. Later that fall, Doc was fired at the Monarch. Allen had his reasons. As Doc’s consumption worsened, he drank more and he was medicating himself with

for example, the wife of the USA president Abraham Lincoln, was a laudanum addict, as was the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge

for example, the wife of the USA president Abraham Lincoln, was a laudanum addict, as was the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge , who was famously interrupted in the middle of an opium-induced writing session of Kubla Khan by a "person from Porlock". Initially a working class drug, laudanum was cheaper than a bottle of gin

, who was famously interrupted in the middle of an opium-induced writing session of Kubla Khan by a "person from Porlock". Initially a working class drug, laudanum was cheaper than a bottle of gin  or wine, because it was treated as a medication for legal purposes and not taxed as an alcoholic beverage.

or wine, because it was treated as a medication for legal purposes and not taxed as an alcoholic beverage.For an upscale operation like Allen’s, these circumstances would have provided enough reason to fire Doc, but he had another reason as well. He was in business with Thomas Duncan, a shady character who had been part of the “Sloper” faction Doc had confronted in Tombstone. In fact, John Tyler, the leader of the Slopers and a sworn enemy of Doc’s, was hired to replace him as a dealer.

Doc did not take the firing well. He exchanged heated words with both Allen and Tyler. He moved down the street to Mannie Hyman’s as a dealer and played cards occasionally at John Morgan’s Board of Trade. But Doc’s work habits proved to be a problem at Hyman’s as well, and Doc found himself struggling to survive. That winter, he later testified, he had several bouts with pneumonia. Fragile, broke and down on his luck, Doc was vulnerable in a way he had never been before.

That was when the Slopers chose to go after him. A Leadville correspondent of the Tucson Citizen stated, “Tyler and his friends did everything they could to prejudice the public against Holiday.”

Doc endured humiliation and provocations that, in former times, he would not have tolerated. For the first time in his life, he asked for help. He told the police on more than one occasion that the Tyler crowd was out to kill him. This period was in many ways the nadir of his life. With tears running down his cheeks, he told a newspaperman who had befriended him, “I am afraid to defend myself, and these cowards kick me because they know I am down. I haven’t a cent, have few friends and they will murder me yet before they are done.”

The Tyler faction overplayed its hand, however. One local editor wrote, “There is much to be said of Holliday—he has never since his arrival here made any bad breaks or conducted himself in any other way than a quiet and peaceable manner. The other faction do not bear this sort of reputation.”

His fight with Billy Allen was a byproduct of this situation, but after Doc was indicted for assault with intent to kill Billy, he tried to restore a sense of normalcy to his life. In November, he served as a member of the mounted brigade of special police formed to guarantee order at the polls during the gubernatorial election. In December, his trial was set for the spring term in 1885. Doc passed the winter quietly. He was well enough to attend a dance sponsored by the Miner’s Union on February 27, 1885. When his trial was held on March 27 and 28, the jury deliberated only briefly before acquitting him.

A few days later, he left Leadville. He may have traveled to New Orleans for a reunion with his father, Henry Burroughs Holliday, who was in town for a gathering of Mexican War veterans. Zan Griffith, a young man who traveled with Henry to New Orleans, always insisted that Doc met them there. According to accounts from family sources, father and son settled their differences, and Henry urged Doc to return to Georgia with him. Doc declined. He was back in Leadville by June, where he pulled a gun in Colorado for the last time to collect a $50 debt from gambler Curly Mack.

That summer, the big news was the mining boom in Butte, Montana. Word had it that Butte’s production not only outstripped Leadville, but all of Colorado combined. More than a few Leadville lights headed for Butte, and in July, the Butte newspapers announced that Doc was in town. He was reportedly back in Leadville in October. Gossip spread that the Tyler-Holliday quarrel might reopen, and the marshal took steps to prevent it. Doc returned to Butte. He kept a low profile until February 1886, when he was indicted for flourishing a pistol. He was not arrested, because he was under a doctor’s care, but he caught a train east the next evening.

The Leadville Daily and Evening Chronicle reported on July 1 that Doc had eventually returned to Colorado, “since which time he has been roaming.” He stayed at the Metropolitan Hotel in Denver before visiting Pueblo in May. In June, a reporter from the New York Sun caught up to him in Silverton and produced a highly sensational account of Doc’s life that was widely reprinted. It was blood-and-thunder clear through, but it gave Doc a chance to deny that he was a killer and even to claim “some credit” for what he had done in his life.

He returned to Denver. Wyatt Earp’s wife, Sadie, later claimed that Doc and Wyatt had a brief reunion in the lobby of a Denver hotel, where the two old comrades said their last goodbyes. On August 3, 1886, Doc was arrested as part of a local crackdown to rid the town of unsavory characters. He was charged with vagrancy, and ordered to leave Denver. He caught the train “home” to Leadville.

The day after Doc’s arrest in Denver, the Boston Daily Globe published an interview with Bat Masterson about “Doc Holliday’s Career.” Masterson told the reporter, “Last winter he went up to Butte City and contracted a severe cold, which I am afraid is going to do him up.”

Doc wintered in Leadville, but his health was deteriorating rapidly. In May 1887, he caught the stage to Glenwood Springs, hoping the sulphur springs would offer some relief. But he was dying. By September, he was confined to bed, in his hotel room, often delirious. During his last month, he slipped in and out of a coma. News of his hopeless condition prompted Leadville sports to collect money to assist in his care, but the “purse” arrived too late. On the morning of November 8, 1887, Doc Holliday died.

Doc’s legend, although largely built around events in Tombstone, Arizona,

On the same day that he died, the Leadville Daily and Evening Chronicle wrote of him: “There is scarcely one in the country who had acquired a greater notoriety than Doc Holliday, who enjoyed the reputation of having been one of the most fearless men on the frontier, and whose devotion to his friends in the climax of the fiercest ordeal was inextinguishable. It was this, more than any other faculty, that secured for him the reverence of a large circle who were prepared on the shortest notice to rally to his relief.”

No comments:

Post a Comment