In 1872, Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, in part, set the stage for the expedition to the Black Hills. In a letter written on March 28, l872, Secretary Delano, responsible for the Sioux territorial rights in the region, said:

In 1872, Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, in part, set the stage for the expedition to the Black Hills. In a letter written on March 28, l872, Secretary Delano, responsible for the Sioux territorial rights in the region, said:"I am inclined to think that the occupation of this region of the country is not necessary to the happiness and prosperity of the Indians, and as it is supposed to be rich in minerals and lumber it is deemed important to have it freed as early as possible from Indian occupancy. I shall, therefore, not oppose any policy which looks first to a careful examination of the subject...Delano's remarks were in direct contradiction of terms defined in the l868 Laramie Treaty that states: "...no persons except those designated herein ... shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory described in this article."

If such an examination leads to the conclusion that country is not necessary or useful to Indians, I should then deem it advisable...to extinguish the claim of the Indians and open the territory to the occupation of the whites."

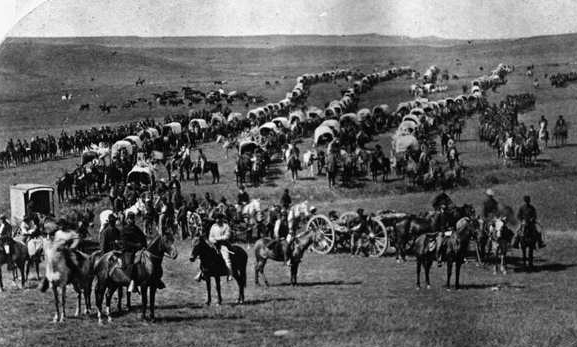

The expedition departed on July 2, 1874. The mile-long procession was lead by a buckskin-clad Custer on his favorite bay thoroughbred at the head of ten Seventh Cavalry companies,

The expedition departed on July 2, 1874. The mile-long procession was lead by a buckskin-clad Custer on his favorite bay thoroughbred at the head of ten Seventh Cavalry companies,  followed by two companies of infantry, scouts and guides. The detachment comprised more than l, 000 troops and one black woman, Sarah Campbell, the expedition's cook.

followed by two companies of infantry, scouts and guides. The detachment comprised more than l, 000 troops and one black woman, Sarah Campbell, the expedition's cook. Six-mule teams pulled 110 white canvas-topped wagons, horse-drawn Gatling guns and cannons, and three hundred head of cattle trailed to provide meat for the troops. A scientific corps included a geologist and his assistant,

Six-mule teams pulled 110 white canvas-topped wagons, horse-drawn Gatling guns and cannons, and three hundred head of cattle trailed to provide meat for the troops. A scientific corps included a geologist and his assistant, a naturalist, a botanist, a medical officer, a topographical engineer, a zoologist, and a civilian engineer. Two miners, Horatio N. Ross and William T. McKay, were attached to the scientific corps. Custer also brought a photographer, newspaper correspondents, the company's band, hunting dogs, the son of U. S. President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as his younger brothers, Tom and Boston.

a naturalist, a botanist, a medical officer, a topographical engineer, a zoologist, and a civilian engineer. Two miners, Horatio N. Ross and William T. McKay, were attached to the scientific corps. Custer also brought a photographer, newspaper correspondents, the company's band, hunting dogs, the son of U. S. President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as his younger brothers, Tom and Boston.This was not the usual military expedition. The Seventh Cavalry band played for the troops in the mornings as they broke camp and played concerts in the evenings.

Troopers leaned from their horses to pick flowers. The large hospital tent served as a dining room for Custer and his staff. Wine bottles visible in Illingworth's photographs indicate they dined in civilized style. Moving southwest, the expedition reached the Belle Fourche River

Troopers leaned from their horses to pick flowers. The large hospital tent served as a dining room for Custer and his staff. Wine bottles visible in Illingworth's photographs indicate they dined in civilized style. Moving southwest, the expedition reached the Belle Fourche River  carving his name and date at the top, as he did on other lofty locations in the Hills. W. H. Illingworth set up his bulky equipment to photograph the string of white-topped wagons stretching along the valleys, wagons that would have to be lowered into gulches by ropes and chains that

carving his name and date at the top, as he did on other lofty locations in the Hills. W. H. Illingworth set up his bulky equipment to photograph the string of white-topped wagons stretching along the valleys, wagons that would have to be lowered into gulches by ropes and chains that  dug deep grooves into sturdy trees.In mid-July, the expedition was camped in an open area east of the present town of Custer. Horatio Ross made the initial discovery of gold along French Creek. Custer wasted little time in dispatching the news to Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory.

dug deep grooves into sturdy trees.In mid-July, the expedition was camped in an open area east of the present town of Custer. Horatio Ross made the initial discovery of gold along French Creek. Custer wasted little time in dispatching the news to Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory. Bearing the news to the outside world, courier Charley Reynolds made the 115-mile ride to Fort Laramie in four nights, hiding during the day to escape detection by any hostile Indians. From Fort Laramie, Custer's reports were telegraphed to General Terry in St. Paul.

Bearing the news to the outside world, courier Charley Reynolds made the 115-mile ride to Fort Laramie in four nights, hiding during the day to escape detection by any hostile Indians. From Fort Laramie, Custer's reports were telegraphed to General Terry in St. Paul. After reading through descriptions of beautiful valleys filled with lush grasses, flowing streams of clear, cold water, wild berries and flowers, Terry finally arrived at the core of the 3,500-word dispatch:

After reading through descriptions of beautiful valleys filled with lush grasses, flowing streams of clear, cold water, wild berries and flowers, Terry finally arrived at the core of the 3,500-word dispatch:"... gold has been found at several places, and it is the belief of those who are giving their attention to this subject that it will be found in paying quantities. I have on my table forty or fifty small particles of pure gold...most of it obtained today from one panful of earth."

Newspapers in the United States, and around the world, spread the word of the gold discovery by the last week of July. Back at French Creek, Horatio Ross, 20 men, and Sarah Campbell drew up papers and staked their claim for District No. l, the Custer Mining Company, before the expedition headed north. The expedition explored the central and northern Black Hills, and then exited the Hills near Bear Butte.

Horatio Ross, 20 men, and Sarah Campbell drew up papers and staked their claim for District No. l, the Custer Mining Company, before the expedition headed north. The expedition explored the central and northern Black Hills, and then exited the Hills near Bear Butte.

The nearly 1,200-mile expedition took sixty days, arriving back at Fort Abraham Lincoln on August 30, 1874. By the time Custer returned, the Black Hills gold rush was on. In Cheyenne and Virginia City, Sioux City

Sioux City and Sidney, Helena and Bismarck, groups of gold-hungry men prepared for prospecting trips into the forbidden Black Hills.

and Sidney, Helena and Bismarck, groups of gold-hungry men prepared for prospecting trips into the forbidden Black Hills.

The nearly 1,200-mile expedition took sixty days, arriving back at Fort Abraham Lincoln on August 30, 1874. By the time Custer returned, the Black Hills gold rush was on. In Cheyenne and Virginia City,

Sioux City

Sioux City and Sidney, Helena and Bismarck, groups of gold-hungry men prepared for prospecting trips into the forbidden Black Hills.

and Sidney, Helena and Bismarck, groups of gold-hungry men prepared for prospecting trips into the forbidden Black Hills.

George Armstrong Custer didn't live to see the full impact of his 1874 expedition, nor did Tom and Boston Custer, or scouts Bloody Knife and Charley Reynolds. Many of the same men who accompanied him into the Black Hills died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn two years later.

Many of the same men who accompanied him into the Black Hills died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn two years later.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as Custer’s Last Stand and the Battle of Greasy Grass Creek) took place June 25-26, 1876, during the Great Sioux War of 1876-77. Many of the same men who accompanied him into the Black Hills died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn two years later.

Many of the same men who accompanied him into the Black Hills died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn two years later. General George Custer led 700 US troops into defeat (with more than 250 casualties) at the hands of about 900 Native American warriors, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse

General George Custer led 700 US troops into defeat (with more than 250 casualties) at the hands of about 900 Native American warriors, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse

14 years after the LBH the Sioux are still at war and want to start things up again with their ghost dance, the Sioux were asked to surrender their weapons but didn't. When the 7th searched their personal belongings for the modern weapons that they claimed they didnt have the shooting started killing many of the soldiers involved with the search. The Army responded with cannon fire on the mass of indians involved,

A note of interest: contemporary archeological analysis of the LBH site

also shows that far less rounds were even fired than expected, given the last stand theory. This is also supported by Indian accounts of the cartridge belts (a prized item of booty) taken from Troopers bodies after the battle. The Indians reported that most of the belts they recovered still had live cartridges in them. This would seem to indicate also more of a panic reaction, than a ground standing response from Custers men.

also shows that far less rounds were even fired than expected, given the last stand theory. This is also supported by Indian accounts of the cartridge belts (a prized item of booty) taken from Troopers bodies after the battle. The Indians reported that most of the belts they recovered still had live cartridges in them. This would seem to indicate also more of a panic reaction, than a ground standing response from Custers men.In addition, the physical amount of rounds expended at the site, is low

The Battle fought in Montana Territory in June 1876, is the most often discussed fight of the Indian wars.

There are also many misconceptions about Lt. Col. George A. Custer and the 7th Cavalry, among them being that Custer had long yellow hair and that he and his regiment carried sabers into the battle. In reality, Custer's hair was cut short, and the regiment left its sabers behind.

An examination of 10 of the major myths about the Battle of the Little Bighorn follows. The first two myths are widely held fallacies that do not require Indian testimony to discredit; the last eight myths are largely discredited by eyewitness accounts of those on the winning side.

Custer and All His Men Were Killed

The 7th Cavalry on June 25, 1876, consisted of about 31 officers, 586 soldiers, 33 Indian scouts and 20 civilian employees. They did not all die. When the smoke cleared on the evening of June 26, 262 were dead, 68 were wounded and six later died of their wounds. Custer's Battalion – C, E, F, I and L companies – was wiped out, but the majority of the seven other companies under Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen

survived.

survived.Fields of fire, and their patterns moving forward over the course of a battle, can be charted with a great degree of accuracy, by analyzing the unique firing pin marks imprinted on spent cartridges.

Those examined at the Ford area of the LBH River show scant evidence of any type of coordination at all- and plenty of evidence of random discharges of weapons 'wild firing' in multiple directions at once- in the ground, in the airCuster Disobeyed His Orders

Many Custerphobes insist Custer violated Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry's orders. We only need to read Terry's written instructions to clarify the situation. Terry wrote that he "places too much confidence in your zeal, energy, and ability to wish to impose upon you precise orders which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the enemy." Terry gave Custer suggestions that he should attempt to carry out, "unless you shall see sufficient reason for departing from them."

In addition to the written orders, Terry entered Custer's tent before he left on his final march, and told him, "Use your own judgment and do what you think best if you strike the trail."

Even using binoculars from the traditional Plains Indian lookout known as the Crow's Nest, Colonel Custer of the 7th Cavalry had trouble seeing the village in the valley some 15 miles away. His scouts told him a large village was there. He believed them, but he wanted to wait one more day, until the morning of June 26, 1876, to attack. He told Half Yellow Face, "I want to wait until it is dark, and then we will march." The Crow scout replied, "These Sioux…have seen the smoke of our camp," and argued that they must attack immediately.

Custer still wanted to wait. Another Crow, White Man Runs Him, said, "That plan is no good, the Sioux have already spotted your soldiers." Red Star, an Arikara, concurred that the Crows were right, and believed that Custer must "attack at once, that day, and capture the horses of the Dakotas [Sioux]." Shortly after, soldiers discovered Indians rummaging through some supplies they had dropped on the back trail. Custer now knew his scouts were right. He followed their advice and attacked immediately. Custer did listen to his scouts.

The Indian Village Was Immense

Traditionally, the village on the Little Bighorn has been depicted as the largest ever seen in the West. Actually there were at least one dozen villages larger, and geographical and spatial considerations illustrate the impossibility of the exaggerated size estimations. A village that has been depicted as large as six miles long and one mile wide, in reality was 11⁄2 miles long and one-quarter mile wide. It contained about 1,200 lodges and perhaps 1,500 warriors. Custer was not "crazy" for attacking.

The Indians told us the village size. Pretty White Buffalo said that the Cheyenne and Sans Arc camps

was north of the Santee camp, which was the northernmost of the circles. Two Moon said that the village stretched from Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa camp at Shoulder Blade Creek, to the Cheyenne camp at Medicine Tail's place. Wooden Leg stated that the Cheyenne camp was just a little upstream and across from Medicine Tail Coulee,

was north of the Santee camp, which was the northernmost of the circles. Two Moon said that the village stretched from Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa camp at Shoulder Blade Creek, to the Cheyenne camp at Medicine Tail's place. Wooden Leg stated that the Cheyenne camp was just a little upstream and across from Medicine Tail Coulee, in the south. Standing Bear and Flying Hawk both produced maps that showed the northernmost limit of the camp to be south of Medicine Tail Creek.

in the south. Standing Bear and Flying Hawk both produced maps that showed the northernmost limit of the camp to be south of Medicine Tail Creek.The Indians showed us that the camp conformed to the river and was, at most, 11⁄2 miles long. It was a large camp, certainly, but it was not several miles long and unconquerable.

Sitting Bull Set Up an Ambush

It is said that the Indians knew Custer and the 7th Cavalry were coming, and set a trap. They did no such thing. Pretty White Buffalo said that no one expected an attack; the young men were not even out watching for the soldiers. "I have seen my people prepare for battle many times," she said, "and this I know: that the Sioux that morning had no thought of fighting."

Moving Robe was digging wild turnips with other women several miles from camp when she saw a cloud of dust rise beyond the bluffs in the east. She saw a warrior riding by, shouting that soldiers were only a few miles away, and that the women, children and old men should run for the hills in the other direction.

Antelope Woman (Kate Bighead) was bathing in the river with many others. Scores of naked men, women and children were in the river and not expecting a battle. Neither were many others playing or fishing along the stream. Everyone was having a good time, said Antelope, and no one was thinking about any battle.

Low Dog said the sun was about at noon, and he was still asleep in his lodge. He awoke to the shouts of soldiers, but thought it was a false alarm. "I did not think it possible that any white men would attack us," he said.

his photograph depicts the grave of Myles Keogh. Born in Ireland, Keogh was an expert horseman who had been a colonel in the cavalry in the Civil War. Like many officers, including Custer, he carried a lesser rank in the postwar Army. He was actually a captain in the 7th Cavalry, but his grave marker, as was customary, notes the higher rank he carried in the Civil War.

his photograph depicts the grave of Myles Keogh. Born in Ireland, Keogh was an expert horseman who had been a colonel in the cavalry in the Civil War. Like many officers, including Custer, he carried a lesser rank in the postwar Army. He was actually a captain in the 7th Cavalry, but his grave marker, as was customary, notes the higher rank he carried in the Civil War.

Keogh had a prized horse named Comanche, which survived the battle at Little Bighorn despite considerable wounds. One of the officers who discovered the bodies recognized Keogh's horse, and saw to it that Comanche was transported to an Army post. Comanche was nursed back to health and was regarded as something of a living monument to the 7th Cavalry.Legend has it that Keogh introduced the Irish tune "Garryowen" to the 7th Cavalry, and the melody became the unit's marching song. That could be true, however the song had already been a popular marching tune during the Civil War.

A year after the battle, Keogh's remains were disinterred from this grave and returned to the east, and he was buried in New York State.

After breakfast, White Bull left his wife's lodge and went to tend the horses with no thoughts of any approaching danger. When he heard a man yelling an alarm, he climbed a hill and could see the soldiers approaching. He jumped on his best horse and drove the ponies back to camp.Standing Bear awoke late that morning. While they ate breakfast, his uncle said, "After you are through eating you had better go and get the horses, because something might happen all at once, we never can tell."

Before they could finish eating, there was a commotion outside, and Standing Bear learned his uncle's premonition was correct. The soldiers were coming. They had been surprised.

Wooden Leg had been to a dance the night before, and slept late that morning. He and his brother Yellow Hair went to the river and found many Indians splashing in the water. The brothers found a shade tree and dozed off. Suddenly an old man called out: "Soldiers are here! Young men, go out and fight them."

Red Feather slept late that morning and awoke to the words: "Go get the horses – buffaloes are stampeding!" Indians began dashing into the camp with the ponies. One, known as Magpie, shouted, "Get away as fast as you can, don't wait for anything, the white men are charging!" Red Feather could see soldiers firing into Sitting Bull's camp. Some Hunkpapas and Oglalas, caught up in the early panic, ran away.

Runs the Enemy heard that soldiers were coming, but did not believe it. He sat back down with the men and continued smoking. Rain in the Face admitted the soldiers came to the valley without warning. "It was a surprise," he said.

Sitting Bull, the chief who was said to have masterminded the ambush by the Indians, was caught up in the confusion. When the soldiers attacked, his young wife, Four Robes, was so frightened that she grabbed only one of her infant twins and ran to the hills. When asked where the second child was, she realized she had left it behind, and raced back to the lodge to retrieve it. Later, the one left behind received the name Abandoned One. This was not the household of a man who supposedly knew soldiers were coming and set a trap for them.

It is apparent from the Indian reactions that Custer had surprised the camp. There was no ambush. Custer's approach was successful. In spite of attacking in broad daylight, he did surprise the village.

Custer's Tactics Were Faulty

It is said that Custer foolishly divided his force and allowed the regiment to be defeated in detail. Yet, using part of a force to fix the enemy in front, and sending another portion to envelop the flank is a standard tactic of professional armies. While Major Marcus Reno attacked the southern end of the village, Custer made a flank march to the north along the river bluffs. The Indians, snapping out of their initial surprise, counterattacked Reno and chased him across the river to the east bank. When they climbed the bluffs, they had another surprise: Custer was already beyond them, 11⁄2 miles north and closer to the village than the Indians were.

White Bull went up the bluffs where he saw something of great importance. "Where we were standing on the side of the hill we saw another troop moving from the east toward the north where the camp was moving," he exclaimed.

One Bull found a vantage point on the hill and saw more troops coming from the south, leading what appeared to be pack mules. But a bigger problem was the troop force to the north. Soldiers were already beyond the Indians and were heading toward the other end of the camp.

American Horse was in the valley while Reno's survivors climbed the hill. When he turned to the river, he heard a man's voice calling out that more bluecoats were moving to attack the lower village, American Horse's own people. He spun his horse around and quickly headed north.

Fears Nothing reached the river and heard an Indian on the east bank calling that more soldiers were coming down from behind the ridge. He rode up the bluffs to see for himself and clambered back down. Once in the valley, he galloped north toward the mouth of Medicine Tail Creek.

Runs the Enemy noticed two Indians waving blankets on the eastern bluffs. Crossing over with another Indian, he heard them yell that the soldiers were "coming, and they were going to get our women and children." He continued to the crest and the sight shocked him. "As I looked along the line of the ridge they seemed to fill the whole hill," he said. "It looked as if there were thousands of them, and I thought we would surely be beaten." Runs The Enemy raced downhill, across the river and back down the valley.

Wooden Leg had climbed a hill north of Reno's hilltop position when another Indian cried out: "Look! Yonder are other soldiers!" Peering downriver, Wooden Leg saw them on the distant hills. The news spread quickly, and the Indians began to ride after them to meet this other threat.

Short Bull was busy driving Reno out of the valley and into the hills. He never noticed Custer until Crazy Horse rode up with his men.

"Too late! You've missed the fight!" Short Bull called to him.

"Sorry to miss this fight!" Crazy Horse laughed. "But there's a good fight coming over the hill."

Short Bull looked where Crazy Horse pointed. For the first time he saw Custer and his men pouring over a hill. "I thought there were a million of them," he said.

"That's where the big fight is going to be," Crazy Horse predicted. "We'll not miss that one."

Many Indians who chased Reno up the bluffs also realized that there were more soldiers already north of them, in a position to interpose themselves between the warriors and the village. Moving along a ridge above Medicine Tail Coulee, less than two miles away, was Custer's Battalion. It was a shock. Custer had surprised them not once, but twice. His tactics were working.

Custer Was Killed at the River

One of the major misconceptions of the Little Bighorn fight is that Custer was shot down in a midstream charge while crossing the river. The idea stems from two sources: one was the Lakota White Cow Bull, and the other was two Crow scouts who were not there. Many other Indian eyewitnesses who were there never said anything of the sort.

Two Moon said that Cheyenne guards were already posted on the east bank when Custer rode down. In addition, many Lakotas had already crossed to the east side. Warriors were across the river, some going upstream and some downstream, trying to get on each side of the soldiers.

Yellow Nose said he and his companions were already on the east side of the river when the soldiers first fired at them.

From the east bank of the river, White Shield saw that the troops were heading straight for them, and he believed they would break through and get across the river. When the Gray Horses (Company E) got close to the river, they dismounted, and both sides fired at each other.

Bobtail Horse said the soldiers began shooting as they neared the ford leading to the camp. He said: "Let us get in line behind this ridge and try to stop or turn them. If they get in camp they will kill many women." Bobtail Horse said that his "party had not advanced toward Custer, but were on the bank of the Little Horn on the same side as Custer."

The soldiers advanced, but, "the ten Indians were firing as hard as they could and killed a soldier," Bobtail Horse explained. The man's horse ran on ahead, and Bobtail Horse caught it. The soldiers finally stopped. This all happened on the east bank.

Red Hawk was fighting Reno's men, but went north in time to see a second group of soldiers coming down the ridge in three divisions. They did not make it to the river, he said. The first division only got to a point about one-half to three-quarters of a mile from the water.

Lone Bear said the soldiers got near the river, dismounted and began leading their horses, but they never got to the river. Lone Bear watched as large numbers of warriors, both mounted and on foot, crossed over to the east bank and started after Custer before he reached the stream.

More warriors indicated the confrontation occurred east of the river. Kill Eagle said, "The Indians crossed the creek and then the firing commenced." Wooden Leg said that the first three Cheyennes to cross the river were Bobtail Horse, Roan Bear and Buffalo Calf, and they fired on Custer while he was "far out on the ridge." He Dog said 15 or 20 Indians fought the troopers from the east side of the stream – near the dry creek, but not near the river. Standing Bear also said that the Indians crossed the river as soon as Custer came in sight. They took position behind a low ridge and were reinforced rapidly as more warriors crossed over. "There was no fighting on the creek," Standing Bear said. Bobtail Horse, who was right there, indicated without hesitation that they were all on the east bank, on the same side as Custer. Two years after the fight, Hump, Brave Wolf and Ice told 5th Infantry Lieutenant Oscar F. Long that the Indians crossed the river before Custer could possibly have forded. They had already gained a small hill on the north side of the Little Bighorn and placed themselves between Custer and the river.

It is clear from the explanations of the Indians who were there that Custer's soldiers never got across the river, or even into it; the Indians were already on the east (north) bank fighting them. Where do we get the idea that Custer was killed in the river? Mostly from White Cow Bull. His story has caused more mischief than almost any of the tales that have been circulated about the battle.

It is only White Cow Bull who supposedly said that he and Bobtail Horse shot a buckskin-clad soldier in the river. Neither Bobtail Horse nor any of the other Indians who were there mention anything of the sort – they don't even say White Cow Bull was there. Yet, White Cow Bull says that he, almost single-handed, stopped a full-scale cavalry charge in midstream. No other Lakota or Cheyenne saw it. They were not fighting on the river, but east of it. White Cow Bull's story is just that – bull.

The Crow scouts Goes Ahead and White Man Runs Him reportedly told stories of Custer dying in the river. Goes Ahead's tale comes from his wife, Pretty Shield, who was not there either, but said little other than Custer drank too much and rode into the river and died. White Man Runs Him did not see Custer, but heard later that Custer was hit in the chest by a bullet and fell into the water. From such tales grew the myth that Custer was killed at the river. It did not happen.

Crazy Horse's Ride to the North

One standard tale of the battle involves the legendary ride of Crazy Horse. The story goes that Crazy Horse, with his tactical genius, judged the situation in a flash, gathered hundreds of his warriors, went north down the valley, crossed the river, swung east and swept down on an unsuspecting Custer from the north, completely surprising and overwhelming the befuddled commander.

Many historians and novelists have followed this scenario: Cyrus Brady, George Hyde, Charles Kuhlman, William Graham, Mari Sandoz, Edgar Stewart, David H. Miller, Stephen Ambrose, Henry and Don Weibert, James Welch, Robert Utley, Evan Connell, Jerry Greene and Doug Scott. A slight variation on this theme comes from Richard Fox; he has Crazy Horse approaching from Deep Ravine. With all those historians concurring at one time or another over the years (some have since modified their interpretation), the story must be true.

It is not.

How did it really happen? Again, the warriors who were there told us where Crazy Horse went. After fighting Reno, Crazy Horse and Flying Hawk went back to the village to drop off some wounded warriors. They immediately went to Medicine Tail Ford, where Short Bull and Pretty White Buffalo saw Crazy Horse crossing the river. He was next located in the area of Calhoun Hill by numerous Indians who fought with him that day, including Foolish Elk, Lone Bear, He Dog, Red Feather and Flying Hawk. White Bull rode from the bluffs where Reno had retreated, directly north on the east side of the river. He approached Calhoun Hill from up Deep Coulee and worked around the hill where he joined Crazy Horse and his men, already fighting. Had Crazy Horse gone on his mythical northern sweep, or done half the deeds ascribed to him, he could not have been fighting near Calhoun Hill in this phase of the battle.

Crazy Horse was very reticent about speaking to white recorders. His spokesman, Horned Horse, said that the soldiers' assault was a surprise. The Indians had no plan of ambush. Crazy Horse believed Custer mistook the women and children stampeding in a northerly direction down the valley for the main body of Indians. The warriors merely divided into two groups, one staying between the noncombatants and Custer and the other circling his rear.

That is all there is to it. Only after the collapse of the Calhoun-Keogh position did Crazy Horse continue north where he may have, finally, confronted the last of Custer's men making their stand on the far knob of the ridge. Or maybe not. Flying Hawk indicated that during the final phase of the battle, Crazy Horse jumped on his pony and chased off after one of the last fleeing troopers. Crazy Horse likely had nothing at all to do with the final fight on Last Stand Hill. He did not make a several mile sweep down the valley and hit Custer near Last Stand Hill from the north, and he did not attack from up Deep Ravine.

Much of this incorrect story stemmed from Gall. Edward Godfrey recorded him as saying, "Crazy Horse went to the extreme north end of the camp." He turned right and went up a very deep ravine and "he came very close to the soldiers on their north side." Remember, however, that the northern end of the camp was at Medicine Tail Coulee, not three miles farther, as many white historians believed, and "north" to most Indians, is "east" to white observers.

Why did we get it so wrong? It developed from a number of factors: different terrain perceptions between Indian and white, white exaggeration of the village size, poor critical examination of the accounts and a reluctance to take the time to re-research the primary sources. An incorrect premise was accepted and perpetuated with each telling, and Crazy Horse's ride has drifted out of the realm of history and into the land of fantasy.

There Was No Last Stand

Of late there have been archaeological studies that have shined new light on some of the mysteries of the battle. One of them, by Richard Fox, has taken the stance that the Custer battle had "no famous last stand," and that the Last Stand is a myth, determined mainly because of artifact clustering patterns and because some men ran toward the river at the end of the fight. Certainly, there was no Last Stand as in the 1941 movie They Died With Their Boots On, but there was a stand.

Good Voiced Elk said, "No stand was made until the soldiers got to the end of the long ridge…."

Flying By rode Battle Ridge to the north where he saw bodies of the soldiers who had been killed all the way along his path. As far as he could see there had been only one stand, and it was made in the place where Custer would be killed, down at the end of the long ridge.

Lone Bear said the fight on Custer Hill was at close quarters, and, "There was a good stand made."

Gall neared the end of the ridge where the last soldiers were making a stand, he said, and, "They were fighting good."

Lights said the stand made at Custer Hill was longer than anywhere else on the field.

Two Eagles said the most stubborn stand by the soldiers was made on Custer Hill.

Red Hawk said the bluecoats were "falling back steadily to Custer Hill where another stand was made," and, "Here the soldiers made a desperate fight."

Iron Hawk saw 20 mounted men and about 30 men on foot on Last Stand Hill. "The Indians pressed and crowded right in around them on Custer Hill," he said. But the soldiers were not yet ready to die. Said Iron Hawk, "They stood here a long time."

He Dog participated in the chase that broke the soldiers' line, and helped drive the fleeing troopers along the ridge. At the far end, Custer's men were putting up a good fight.

Red Hawk said that only after making a desperate fight on Custer Hill did the remaining soldiers retreat downhill.

Flying Hawk said they kept after the fleeing soldiers until they got to where Custer was making a stand on the ridge. There "the living remnant of his command were now surrounded."

Although impressions of the stand's time length and degree of intensity vary among the observers, the fact that it took place cannot be erased. Soldiers defending the northern portion of Custer's field inflicted most of the Indian casualties – the best defense was not made at Calhoun Hill. The time spent in their fight and the results of their shooting are all the evidence we need to show that they defended their ground tenaciously. An interpretation claiming that few government cartridges were found on Custer Hill cannot change this. Although some soldiers ran from Custer's Hill, they did hold their ground and fight from their position as long as they could. The participating warriors called it a Last Stand. Deal with it.

28 Soldiers Died in Deep Ravine

Recent visitors to the battlefield may have walked down the Deep Ravine Trail to its end and read the interpretive sign. The sign perpetuates another myth: that about 28 soldiers died within the steep-walled gully. It has several quotes from Indians and soldiers who said they saw bodies in the ravine. What are not listed are the statements from eyewitnesses who said that few, if any, bodies were there.

Interpretation should be based on historical and physical evidence whenever possible. Battle relics and bones have been found virtually on every part of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. Where they have not been found is in the trench of the Deep Ravine. When the archaeological record shows no sign of bodies, it ought to be matched with the appropriate historical record – that there were few, if any, bodies in the Deep Ravine. It is incredible that diametrically opposed historical and archaeological interpretations are presented as facts.

Since there is no physical record of soldier bodies in Deep Ravine, the interpretive sign should contain the appropriate historical commentary.

The Oglala warrior He Dog, said, "Only a few soldiers who broke away were killed below toward the river."

Lone Bear said Custer Hill was "the first and only place where the soldiers tried to get away, and only a few from there."

Waterman said, "A few soldiers tried to get away and reach the river, but they were all killed."

Flying By said that "Soldiers were running through [the] Indian lines trying to get away…only four soldiers got into the gully by the river."

Two Moon explained that Custer's men "stayed right out in the open where it was easy to shoot them down. Any ordinary bunch of men would have dropped into a watercourse, or a draw."

Red Hawk tellingly reported, "Some of the soldiers broke through the Indians and ran for the river, but all were killed without getting into it."

Iron Hawk said that at the fight's end, "We looked up and the soldiers all were running….The furthest headstone shows where the second man that I killed lies…probably this was the last of Custer's men to be killed….there was only one soldier sneaking along in the gulch."

Probably the clearest white voice that denies bodies in the Deep Ravine came from eyewitness Lieutenant Charles F. Roe, who was there right after the battle, and whose job it was to return to the field in 1881, rebury the bodies on the ridge and place the stone monument above them. In a letter to Walter Camp in 1911, responding to Camp's persistent, incorrect questions about bodies in the ravine, Roe finally said: "I put up the markers near the deep ravine you speak of. There never was twenty-eight dead men in the ravine, but near the head of said ravine, and only two or three in it."

What can we gather from all this? There were many participants who saw what happened at the Little Bighorn, and we should not discount their stories in favor of speculation from those who did not see the events – neither those who lived in the 19th century nor those who make their livings by writing stories today. It is difficult to debunk the old legends, however. Myths die hard – even when hundreds of eyewitnesses have already told it like it was.

He was basically intending to hold position until the rest of Gen.Terry's, Gen. Crook's and Colonel Gibbon's forces arrived. Reportedly, Terry's troops numbered 600 cavalry and 400 enfantry. Crook's troops consisted of 47 officers, and 1000 men. Gibbon marched with 450 cavalry and infantry. Had Reno and Benteen done their duty it is quite probable the the Indians could have been kept in check until General Terry arrived.

While not a bad thing by itself, it also can be as detrimental to those who are merely seeking the truth as totally discounting the Indian accounts on one hand, and totally discounting the whites accounts on the other. My guess is the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

aveling through the warriors, burdened by either extra ammunition weight or slow mules?

Fact is the same warriors who beat Custer, fought the so called inferior Benteen, Reno command. They survived and he didn't. I believe they weighed up the situation and made a good fortified defense. Tactically they done the best they could with what they had.

Custer had his troops too spread out for fire support and concentration. They were to far away from other battalion support. People say he was just '15 minutes gallop away'. Yes but Benteen had a 1,000 plus warriors in the way!!!

I believe Benteen did not know where Custer was, went to Reno, saw the situation and decided to stay put. Of course there is talk about hearing the Custer fight and not going to aid him. The guy was miles away, with warriors between them and him. When Weir went out they realized it was over by then.

Custer had disregarded orders many times before, like some say Benteen did. Custer also left men behind to their own fate, as they say Benteen did.

Does anyone seriously think that Benteen deliberately left Custer to die?

If Benteen and Reno were flawed it is up to their commander to whip them in shape…and know how much he can trust them. If he couldn't trust them surely wouldn't they had been better where he could keep his eye on them?

They do say Custer had mood swings and maybe that is indicative of some psychological issue? He certainly seemed a different man at officers briefings towards the end.

He wanted glory, live or dead I believe.