The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish, and Irish thrones.

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish, and Irish thrones. James II and VII (14 October 1633O.S. – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February

James II and VII (14 October 1633O.S. – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685 until he was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was the last Roman Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland.

1685 until he was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was the last Roman Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland.

The second surviving son of Charles I, he ascended the throne upon the death of his brother, Charles II. Members of Britain's political and religious elite increasingly suspected him of being pro-French and pro-Catholic and of having designs on becoming anabsolute monarch.

Members of Britain's political and religious elite increasingly suspected him of being pro-French and pro-Catholic and of having designs on becoming anabsolute monarch. When he produced a Catholic heir, the tension exploded, and leading nobles called on his Protestant son-in-law and nephew, William of Orange, to land an invasion army from the Netherlands, which he did

When he produced a Catholic heir, the tension exploded, and leading nobles called on his Protestant son-in-law and nephew, William of Orange, to land an invasion army from the Netherlands, which he did

.After his marriage in November 1677, William became a strong candidate for the English throne if his father-in-law (and uncle) James were excluded because of his Catholicism. During the crisis concerning the Exclusion Bill in 1680, Charles at first invited William to come to England to bolster the king's position against the exclusionists, then withdrew his invitation—after which Lord Sunderland also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.

Nevertheless, William secretly induced the States General to send the Insinuation to Charles, beseeching the king to prevent any Catholics from succeeding him, without explicitly naming James. After receiving indignant reactions from Charles and James, William denied any involvement.

During the crisis concerning the Exclusion Bill in 1680, Charles at first invited William to come to England to bolster the king's position against the exclusionists, then withdrew his invitation—after which Lord Sunderland also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.

also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.

Nevertheless, William secretly induced the States General to send the Insinuation to Charles, beseeching the king to prevent any Catholics from succeeding him, without explicitly naming James. After receiving indignant reactions from Charles and James, William denied any involvement.

]James fled England (and thus was held to have abdicated) in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was replaced by his Protestant elder daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns from William and Mary, when he landed in Ireland in 1689 but, after the defeat of the Jacobite forces by the Williamite forces

and her husband, William III. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns from William and Mary, when he landed in Ireland in 1689 but, after the defeat of the Jacobite forces by the Williamite forces at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James returned to France. He lived out the rest of his life as a pretender at a court sponsored by his cousin and ally, King Louis XIV.

at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James returned to France. He lived out the rest of his life as a pretender at a court sponsored by his cousin and ally, King Louis XIV.

Members of Britain's political and religious elite increasingly suspected him of being pro-French and pro-Catholic and of having designs on becoming anabsolute monarch.

Members of Britain's political and religious elite increasingly suspected him of being pro-French and pro-Catholic and of having designs on becoming anabsolute monarch. When he produced a Catholic heir, the tension exploded, and leading nobles called on his Protestant son-in-law and nephew, William of Orange, to land an invasion army from the Netherlands, which he did

When he produced a Catholic heir, the tension exploded, and leading nobles called on his Protestant son-in-law and nephew, William of Orange, to land an invasion army from the Netherlands, which he did.After his marriage in November 1677, William became a strong candidate for the English throne if his father-in-law (and uncle) James were excluded because of his Catholicism. During the crisis concerning the Exclusion Bill in 1680, Charles at first invited William to come to England to bolster the king's position against the exclusionists, then withdrew his invitation—after which Lord Sunderland also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.

Nevertheless, William secretly induced the States General to send the Insinuation to Charles, beseeching the king to prevent any Catholics from succeeding him, without explicitly naming James. After receiving indignant reactions from Charles and James, William denied any involvement.

During the crisis concerning the Exclusion Bill in 1680, Charles at first invited William to come to England to bolster the king's position against the exclusionists, then withdrew his invitation—after which Lord Sunderland

also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.

also tried unsuccessfully to bring William over, but now to put pressure on Charles.Nevertheless, William secretly induced the States General to send the Insinuation to Charles, beseeching the king to prevent any Catholics from succeeding him, without explicitly naming James. After receiving indignant reactions from Charles and James, William denied any involvement.

]James fled England (and thus was held to have abdicated) in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He was replaced by his Protestant elder daughter, Mary II,

and her husband, William III. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns from William and Mary, when he landed in Ireland in 1689 but, after the defeat of the Jacobite forces by the Williamite forces

and her husband, William III. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns from William and Mary, when he landed in Ireland in 1689 but, after the defeat of the Jacobite forces by the Williamite forces at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James returned to France. He lived out the rest of his life as a pretender at a court sponsored by his cousin and ally, King Louis XIV.

at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, James returned to France. He lived out the rest of his life as a pretender at a court sponsored by his cousin and ally, King Louis XIV.

James is best known for struggles with the English Parliament and his attempts to create religious  liberty for English Roman Catholics and Protestant nonconformists against the wishes of the Anglican establishment. However, he also continued the persecution of the Presbyterian Covenanters in Scotland. Parliament, opposed to the growth of absolutism that was occurring in other European countries, as well as to the loss of legal supremacy for the Church of England, saw their opposition as a way to preserve what they regarded as traditional English liberties. This tension made James's four-year reign a struggle for supremacy between the English Parliament and the Crown, resulting in his deposition, the passage of the Bill of Rights, and the Hanoverian succession. and the Protestant William III and II (who, with his wife, Mary II, James's daughter, had deposed James in 1688) – across the River Boyne near Drogheda

liberty for English Roman Catholics and Protestant nonconformists against the wishes of the Anglican establishment. However, he also continued the persecution of the Presbyterian Covenanters in Scotland. Parliament, opposed to the growth of absolutism that was occurring in other European countries, as well as to the loss of legal supremacy for the Church of England, saw their opposition as a way to preserve what they regarded as traditional English liberties. This tension made James's four-year reign a struggle for supremacy between the English Parliament and the Crown, resulting in his deposition, the passage of the Bill of Rights, and the Hanoverian succession. and the Protestant William III and II (who, with his wife, Mary II, James's daughter, had deposed James in 1688) – across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland. The battle, won by William, was a turning point in James's unsuccessful attempt to regain the crown and ultimately helped ensure the continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

on the east coast of Ireland. The battle, won by William, was a turning point in James's unsuccessful attempt to regain the crown and ultimately helped ensure the continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

The battle took place on 1 July 1690 in the old style (Julian) calendar. This was equivalent to 11 July in the new style(Gregorian) calendar, although today its commemoration is held on 12 July,[1] on which the decisive Battle of Aughrim liberty for English Roman Catholics and Protestant nonconformists against the wishes of the Anglican establishment. However, he also continued the persecution of the Presbyterian Covenanters in Scotland. Parliament, opposed to the growth of absolutism that was occurring in other European countries, as well as to the loss of legal supremacy for the Church of England, saw their opposition as a way to preserve what they regarded as traditional English liberties. This tension made James's four-year reign a struggle for supremacy between the English Parliament and the Crown, resulting in his deposition, the passage of the Bill of Rights, and the Hanoverian succession. and the Protestant William III and II (who, with his wife, Mary II, James's daughter, had deposed James in 1688) – across the River Boyne near Drogheda

liberty for English Roman Catholics and Protestant nonconformists against the wishes of the Anglican establishment. However, he also continued the persecution of the Presbyterian Covenanters in Scotland. Parliament, opposed to the growth of absolutism that was occurring in other European countries, as well as to the loss of legal supremacy for the Church of England, saw their opposition as a way to preserve what they regarded as traditional English liberties. This tension made James's four-year reign a struggle for supremacy between the English Parliament and the Crown, resulting in his deposition, the passage of the Bill of Rights, and the Hanoverian succession. and the Protestant William III and II (who, with his wife, Mary II, James's daughter, had deposed James in 1688) – across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland. The battle, won by William, was a turning point in James's unsuccessful attempt to regain the crown and ultimately helped ensure the continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

on the east coast of Ireland. The battle, won by William, was a turning point in James's unsuccessful attempt to regain the crown and ultimately helped ensure the continuation of Protestant ascendancy in Ireland.

was fought a year later. William's forces defeated James's army of mostly raw recruits.

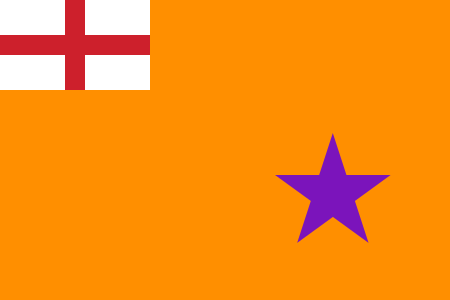

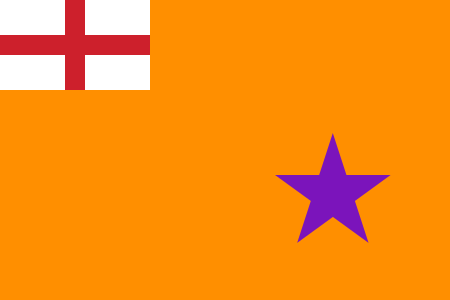

was fought a year later. William's forces defeated James's army of mostly raw recruits. The symbolic importance of this battle has made it one of the best-known battles in the history of the British Isles and a key part of the folklore of the Orange Order. Its commemoration today is principally by the Protestant Orange Institution.The Battle of Aughrim was the decisive battle of the Williamite War in Ireland. It was fought between the Jacobites and the forces of William III on 12 July 1691 (old style, equivalent to 22 July new style), near the village of Aughrim

The symbolic importance of this battle has made it one of the best-known battles in the history of the British Isles and a key part of the folklore of the Orange Order. Its commemoration today is principally by the Protestant Orange Institution.The Battle of Aughrim was the decisive battle of the Williamite War in Ireland. It was fought between the Jacobites and the forces of William III on 12 July 1691 (old style, equivalent to 22 July new style), near the village of Aughrim , County Galway.

, County Galway.The battle was one of the more bloody recorded fought on Irish soil – over 7,000 people were killed. It meant the effective end of Jacobitism in Ireland, although the city of Limerick held out until the autumn The Battle of Aughrim occupied a prominent place in the consciousness of the people. For many the word Aughrim was synonymous with disaster.. loss and defeat..IT is still possible in South Leinster to hear a minor disaster dismissed in the words ‘’ It is not an Aughrim anyhow.The fatal ‘Battle of Aughrim’, fought on 12 July 1691, played a decisive role in determining Irish and European history, and securing Aughrim’s unique place within it.

The Battle has been commemorated by the efforts of the local community, and most significantly that of local Historian Martin Joyce, in partnership with Galway County Council, with the establishment of the Battle of Aughrim Interpretative Centre .In 1689 this War of the Two Kings, or Cogadh an Da Ri moved to Ireland when James landed in Kinsale, County Cork. Two years later, following the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 the war had turned in favour of Willliam but under the command of St ruth the Jacobits were still a force and continued to fight at the Siege of Athlone in 1691 . The battles brought an estimated forty five thousand soldiers from eight European nations to Aughrim; who fought there for a day, at the end of which nine thousand, predominantly Irish, soldiers lay slain.

. The battles brought an estimated forty five thousand soldiers from eight European nations to Aughrim; who fought there for a day, at the end of which nine thousand, predominantly Irish, soldiers lay slain.

. The battles brought an estimated forty five thousand soldiers from eight European nations to Aughrim; who fought there for a day, at the end of which nine thousand, predominantly Irish, soldiers lay slain.

. The battles brought an estimated forty five thousand soldiers from eight European nations to Aughrim; who fought there for a day, at the end of which nine thousand, predominantly Irish, soldiers lay slain.

James army had to retreat and with the Williamite army in pursuit, it later led to the signing of the Limerick Treaty. In Ginkel's army, besides English, Scotch, and Irish, there were Huguenots, Danes, and Dutch, while King James was supported by English, French and Irish.

besides English, Scotch, and Irish, there were Huguenots, Danes, and Dutch, while King James was supported by English, French and Irish.

besides English, Scotch, and Irish, there were Huguenots, Danes, and Dutch, while King James was supported by English, French and Irish.

besides English, Scotch, and Irish, there were Huguenots, Danes, and Dutch, while King James was supported by English, French and Irish.

You can re-live the day that changed the course of Irish and European history at the Battle of Aughrim Interpretative Centre. The centre hosts exhibits and audio video presentations about this historic event to allow you move back in time and place to that fateful day in 1691, through an audio-visual show based on the true and moving account of Captain Walter Dalton who fought at the Battle of Aughrim. Many items found from the site of The Battle of Aughrim has been preserved over the years by local National School headmaster Martin Joyce, and which are now exhibited as part of The Joyce Collection in the Battle of Aughrim Interpretative Centre.

Over the years, the Village’s historic legacy of war and loss has contributed to many cultural and literary responses, including that of the reknown Aughrim Slopes Ceili Band, signature tune ‘The Battle of Aughrim’ The battle, according to one author, was ‘seared into Irish consciousness’, and became known as ‘Eachdhroim an áir’ – Aughrim of the slaughter’. The contemporary Gaelic poet Séamas Dall Mac Cuarta wrote of the Irish dead, ‘It is at Aughrim of the slaughter where they are to be found, their damp bones lying uncoffined.’

John Mulvany 19th century painting ‘The Battle of Aughrim’

Significant also, is a painting of a battle scene from the fatal day in Aughrim by Irish American artist, John Mulvany from 1885. The Painting has only recently been rediscovered by Art Historian, Professor Emeritus, Niamh O’ Sullivan, having been lost in the USA for almost 100 years. Reflecting upon the politics and the nationalist and cultural revival at that time, renown painter John Mulvany, choose to visit the site of the infamous ‘Battle of Aughrim’. ‘’The painting is an example of the artist’s call for inspiration from the prominence of Aughrim in the Nation’s psych as a place and site of national possibility and resurgence.

‘’From near triumph, to resounding defeat, the story of Aughrim was subsequently reclaimed in Irish cultural memory, as an enduring symbol of entitlement, a site for future resurgence’’.The Jacobite position in the summer of 1691 was a defensive one.In the previous year, they had retreated behind the River Shannon, which acted as an enormous moat around the province of Connacht, with strongholds at Sligo,

which acted as an enormous moat around the province of Connacht, with strongholds at Sligo, Athlone and Limerick

Athlone and Limerick guarding the routes into Connacht. From this position, the Jacobites hoped to receive military aid from Louis XIV of France via the port towns and eventually be in a position to re-take the rest of Ireland.

guarding the routes into Connacht. From this position, the Jacobites hoped to receive military aid from Louis XIV of France via the port towns and eventually be in a position to re-take the rest of Ireland.

which acted as an enormous moat around the province of Connacht, with strongholds at Sligo,

which acted as an enormous moat around the province of Connacht, with strongholds at Sligo, Athlone and Limerick

Athlone and Limerick guarding the routes into Connacht. From this position, the Jacobites hoped to receive military aid from Louis XIV of France via the port towns and eventually be in a position to re-take the rest of Ireland.

guarding the routes into Connacht. From this position, the Jacobites hoped to receive military aid from Louis XIV of France via the port towns and eventually be in a position to re-take the rest of Ireland.

Godert de Ginkell, the Williamites' Dutch general, had breached this line of defence by crossing the Shannon at Athlone - taking the town after a bloody siege. The Marquis de St Ruth (General Charles Chalmont), the French Jacobite general,

had breached this line of defence by crossing the Shannon at Athlone - taking the town after a bloody siege. The Marquis de St Ruth (General Charles Chalmont), the French Jacobite general, moved too slowly to save Athlone, as he had to gather his troops from their quarters and raise new ones from rapparee bands and the levies of Irish landowners. Ginkel

moved too slowly to save Athlone, as he had to gather his troops from their quarters and raise new ones from rapparee bands and the levies of Irish landowners. Ginkel  marched through Ballinasloe,

marched through Ballinasloe, on the main road towards Limerick and Galway, before he found his way blocked by St Ruth’s army at Aughrim on the 12th of July 1691. Both armies were about 20,000 men strong. The soldiers of St Ruth’s army were mostly Irish Catholic, while Ginkel's were English, Scottish, Danish, Dutch and French Huguenot(members of William III’s League of Augsburg) and Irish Protestants.

on the main road towards Limerick and Galway, before he found his way blocked by St Ruth’s army at Aughrim on the 12th of July 1691. Both armies were about 20,000 men strong. The soldiers of St Ruth’s army were mostly Irish Catholic, while Ginkel's were English, Scottish, Danish, Dutch and French Huguenot(members of William III’s League of Augsburg) and Irish Protestants.

had breached this line of defence by crossing the Shannon at Athlone - taking the town after a bloody siege. The Marquis de St Ruth (General Charles Chalmont), the French Jacobite general,

had breached this line of defence by crossing the Shannon at Athlone - taking the town after a bloody siege. The Marquis de St Ruth (General Charles Chalmont), the French Jacobite general, moved too slowly to save Athlone, as he had to gather his troops from their quarters and raise new ones from rapparee bands and the levies of Irish landowners. Ginkel

moved too slowly to save Athlone, as he had to gather his troops from their quarters and raise new ones from rapparee bands and the levies of Irish landowners. Ginkel  marched through Ballinasloe,

marched through Ballinasloe, on the main road towards Limerick and Galway, before he found his way blocked by St Ruth’s army at Aughrim on the 12th of July 1691. Both armies were about 20,000 men strong. The soldiers of St Ruth’s army were mostly Irish Catholic, while Ginkel's were English, Scottish, Danish, Dutch and French Huguenot(members of William III’s League of Augsburg) and Irish Protestants.

on the main road towards Limerick and Galway, before he found his way blocked by St Ruth’s army at Aughrim on the 12th of July 1691. Both armies were about 20,000 men strong. The soldiers of St Ruth’s army were mostly Irish Catholic, while Ginkel's were English, Scottish, Danish, Dutch and French Huguenot(members of William III’s League of Augsburg) and Irish Protestants.

The Jacobite position at Aughrim was quite strong. St Ruth had drawn up his infantry along the crest of a ridge known as Kilcommadan Hill. The hill was lined with small stone walls and hedgerows which marked the boundaries of farmers' fields, but which could also be improved and then used as earthworks for the Jacobite infantry to shelter behind. The left of the position was bounded by a bog, through which there was only one causeway, overlooked by Aughrim village and a ruined castle. On the other, open, flank, St Ruth placed his best infantry under his second-in-command, the chevalier de Tessé, and most of his cavalry under Patrick Sarsfield

and most of his cavalry under Patrick Sarsfield .The battle started with Ginkel trying to assault the open flank of the Jacobite position with cavalry and infantry. This attack ground to a halt after determined Jacobite counter-attacks and the Williamites halted and dug in behind stakes driven into the ground to protect against cavalry. The French Huguenot forces committed here found themselves in low ground exposed to Jacobite fire and took a great number of casualties. Contemporaneous accounts speak of the grass being slippery with blood. To this day, this area on the south flank of the battle is known locally as the "Bloody Hollow".[3] In the centre, the Williamite infantry under Hugh Mackay

.The battle started with Ginkel trying to assault the open flank of the Jacobite position with cavalry and infantry. This attack ground to a halt after determined Jacobite counter-attacks and the Williamites halted and dug in behind stakes driven into the ground to protect against cavalry. The French Huguenot forces committed here found themselves in low ground exposed to Jacobite fire and took a great number of casualties. Contemporaneous accounts speak of the grass being slippery with blood. To this day, this area on the south flank of the battle is known locally as the "Bloody Hollow".[3] In the centre, the Williamite infantry under Hugh Mackay  tried a frontal assault on the Jacobite infantry on Kilcommadan Hill. The Williamite troops, mainly English and Scots, had to take each line of trenches, only to find that the Irish had fallen back and were firing at them from the next line. The Williamite infantry attempted three assaults, the first of which penetrated furthest. Eventually, the final Williamite assault was driven back with heavy losses by cavalry and pursued into the bog, where more of them were killed or drowned. In the rout, the pursuing Jacobites manage to spike a battery of Williamite guns.This left Ginkel with only one option, to try to force a way through the causeway on the Jacobite left. This should have been an impregnable position, with the attackers concentrated into a narrow lane and covered by the defenders of the castle there. However, the Irish troops there were short on ammunition. Mackay directed this fourth assault, consisting mainly of cavalry, in two groups - one along the causeway and one parallel to the south. The Jacobites stalled this attack with heavy fire from the castle, but then found that their reserve ammunition, which was British-made, would not fit into the muzzles of their French-supplied muskets. The Williamites then charged again with a reasonably fresh regiment of Anglo-Dutch cavalry under Henri de Massue.

tried a frontal assault on the Jacobite infantry on Kilcommadan Hill. The Williamite troops, mainly English and Scots, had to take each line of trenches, only to find that the Irish had fallen back and were firing at them from the next line. The Williamite infantry attempted three assaults, the first of which penetrated furthest. Eventually, the final Williamite assault was driven back with heavy losses by cavalry and pursued into the bog, where more of them were killed or drowned. In the rout, the pursuing Jacobites manage to spike a battery of Williamite guns.This left Ginkel with only one option, to try to force a way through the causeway on the Jacobite left. This should have been an impregnable position, with the attackers concentrated into a narrow lane and covered by the defenders of the castle there. However, the Irish troops there were short on ammunition. Mackay directed this fourth assault, consisting mainly of cavalry, in two groups - one along the causeway and one parallel to the south. The Jacobites stalled this attack with heavy fire from the castle, but then found that their reserve ammunition, which was British-made, would not fit into the muzzles of their French-supplied muskets. The Williamites then charged again with a reasonably fresh regiment of Anglo-Dutch cavalry under Henri de Massue. Faced with only weak musket fire, they crossed the causeway and reached Aughrim village with few casualties. A force of Jacobite cavalry under Henry Luttrell

Faced with only weak musket fire, they crossed the causeway and reached Aughrim village with few casualties. A force of Jacobite cavalry under Henry Luttrell had been held in reserve to cover this flank. However, rather than counterattacking at this point, their commander ordered them to withdraw, following a route now known locally as "Luttrell's Pass". Henry Luttrell was alleged to have been in the pay of the Williamites and was assassinated in Dublin after the war. The castle quickly fell and its Jacobite garrison surrenderedThe Jacobite general Marquis de St Ruth, after the third infantry rush on the Williamite position up to their cannons, appeared to believe that the battle could be won and was heard to shout, "they are running, we will chase them back to the gates of Dublin". However, as he tried to rally his cavalry on the left to counter-attack and drive the Williamite horse back, he was decapitated by a cannonball. At this point, the Jacobite position collapsed very quickly. Their horsemen, demoralised by the death of their commander, fled the battlefield, leaving the left flank open for the Williamites to funnel more troops into and envelope the Jacobite line. The Jacobites on the right, seeing the situation was hopeless, also began to melt away, although Sarsfield did try to organise a rearguard action. This left the Jacobite infantry on Killcommadan Hill completely exposed and surrounded. They were slaughtered by the Williamite cavalry as they tried to get away, many of them having thrown away their weapons in order to run faster. One eyewitness, George Storey, said that bodies covered the hill and looked from a distance like a flock of sheep.

had been held in reserve to cover this flank. However, rather than counterattacking at this point, their commander ordered them to withdraw, following a route now known locally as "Luttrell's Pass". Henry Luttrell was alleged to have been in the pay of the Williamites and was assassinated in Dublin after the war. The castle quickly fell and its Jacobite garrison surrenderedThe Jacobite general Marquis de St Ruth, after the third infantry rush on the Williamite position up to their cannons, appeared to believe that the battle could be won and was heard to shout, "they are running, we will chase them back to the gates of Dublin". However, as he tried to rally his cavalry on the left to counter-attack and drive the Williamite horse back, he was decapitated by a cannonball. At this point, the Jacobite position collapsed very quickly. Their horsemen, demoralised by the death of their commander, fled the battlefield, leaving the left flank open for the Williamites to funnel more troops into and envelope the Jacobite line. The Jacobites on the right, seeing the situation was hopeless, also began to melt away, although Sarsfield did try to organise a rearguard action. This left the Jacobite infantry on Killcommadan Hill completely exposed and surrounded. They were slaughtered by the Williamite cavalry as they tried to get away, many of them having thrown away their weapons in order to run faster. One eyewitness, George Storey, said that bodies covered the hill and looked from a distance like a flock of sheep.

and most of his cavalry under Patrick Sarsfield

and most of his cavalry under Patrick Sarsfield .The battle started with Ginkel trying to assault the open flank of the Jacobite position with cavalry and infantry. This attack ground to a halt after determined Jacobite counter-attacks and the Williamites halted and dug in behind stakes driven into the ground to protect against cavalry. The French Huguenot forces committed here found themselves in low ground exposed to Jacobite fire and took a great number of casualties. Contemporaneous accounts speak of the grass being slippery with blood. To this day, this area on the south flank of the battle is known locally as the "Bloody Hollow".[3] In the centre, the Williamite infantry under Hugh Mackay

.The battle started with Ginkel trying to assault the open flank of the Jacobite position with cavalry and infantry. This attack ground to a halt after determined Jacobite counter-attacks and the Williamites halted and dug in behind stakes driven into the ground to protect against cavalry. The French Huguenot forces committed here found themselves in low ground exposed to Jacobite fire and took a great number of casualties. Contemporaneous accounts speak of the grass being slippery with blood. To this day, this area on the south flank of the battle is known locally as the "Bloody Hollow".[3] In the centre, the Williamite infantry under Hugh Mackay  tried a frontal assault on the Jacobite infantry on Kilcommadan Hill. The Williamite troops, mainly English and Scots, had to take each line of trenches, only to find that the Irish had fallen back and were firing at them from the next line. The Williamite infantry attempted three assaults, the first of which penetrated furthest. Eventually, the final Williamite assault was driven back with heavy losses by cavalry and pursued into the bog, where more of them were killed or drowned. In the rout, the pursuing Jacobites manage to spike a battery of Williamite guns.This left Ginkel with only one option, to try to force a way through the causeway on the Jacobite left. This should have been an impregnable position, with the attackers concentrated into a narrow lane and covered by the defenders of the castle there. However, the Irish troops there were short on ammunition. Mackay directed this fourth assault, consisting mainly of cavalry, in two groups - one along the causeway and one parallel to the south. The Jacobites stalled this attack with heavy fire from the castle, but then found that their reserve ammunition, which was British-made, would not fit into the muzzles of their French-supplied muskets. The Williamites then charged again with a reasonably fresh regiment of Anglo-Dutch cavalry under Henri de Massue.

tried a frontal assault on the Jacobite infantry on Kilcommadan Hill. The Williamite troops, mainly English and Scots, had to take each line of trenches, only to find that the Irish had fallen back and were firing at them from the next line. The Williamite infantry attempted three assaults, the first of which penetrated furthest. Eventually, the final Williamite assault was driven back with heavy losses by cavalry and pursued into the bog, where more of them were killed or drowned. In the rout, the pursuing Jacobites manage to spike a battery of Williamite guns.This left Ginkel with only one option, to try to force a way through the causeway on the Jacobite left. This should have been an impregnable position, with the attackers concentrated into a narrow lane and covered by the defenders of the castle there. However, the Irish troops there were short on ammunition. Mackay directed this fourth assault, consisting mainly of cavalry, in two groups - one along the causeway and one parallel to the south. The Jacobites stalled this attack with heavy fire from the castle, but then found that their reserve ammunition, which was British-made, would not fit into the muzzles of their French-supplied muskets. The Williamites then charged again with a reasonably fresh regiment of Anglo-Dutch cavalry under Henri de Massue. Faced with only weak musket fire, they crossed the causeway and reached Aughrim village with few casualties. A force of Jacobite cavalry under Henry Luttrell

Faced with only weak musket fire, they crossed the causeway and reached Aughrim village with few casualties. A force of Jacobite cavalry under Henry Luttrell

No comments:

Post a Comment